Reading the Superhero:

Ethics, Crises, and Superboy Punches

Fighting (for) the Law

Daredevil’s entire life is defined by a double bind

Chapter 3:

The Law vs. Justice

Fighting (for) the Law

Superheroes with secret identities tend to have day jobs that complement their more unusual activities: reporters, mild-mannered or otherwise, are well-poised to hear about a crime in progress, scientists of all stripes bring useful knowledge and even more useful gadgets to the fight against supervillains, and rich playboys have a great deal of time on their hands (and even greater financial resources to spend on their costumed adventures).

There is, however, a small subset of superheroes whose fight against crime at first glance looks like an extension of their professional work, but actually functions as its antithesis: lawyers and police. Like military service, law enforcement is more likely to be part of a hero's backstory than their present: DC's Guardian and Marvel's Misty Knight are both former cops who are no longer constrained by police regulations. Some superheroes exercise their powers as part of a science fictional law enforcement agency, which also tends to give them more leeway than ordinary earth cops (the various Green Lanterns; some versions of Hawkman, Bishop of the X-Men).

Only a few actually combine ongoing police work with superheroics: Dick Grayson (Nightwing) served in the Bloohdhaven police force for a brief time; Barry Allen (The Flash) is a forensic scientist with the Central City Police Department; various versions of the Spectre (Jim Corrigan) continued their detective work even after becoming the Spirit of Vengeance, and, more recently Renée Montoya has combined her costumed activity as The Question with legitimate police work, even rising to the rank of Gotham City Police Commissioner. It's unsurprising that so few superheroes are in the police force, since the contrast is not particularly exciting: who wants to read a story about a doorman who moonlights as a security guard?

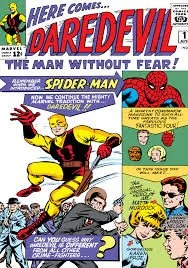

Lawyers are also far from overrepresented among secret identities, but they have had more staying power. At DC, Kate Spencer has alternated between being a district attorney and a defense lawyer while also killing criminals as Manhunter. Image Comics in the 1990s published the adventures of Shadowhawk, who was a lawyer before he put on a costume. At Marvel, Jennifer Walters has been the rare character to maintain both a legal career and a heroic identity (She-Hulk), but this is often in the service of imagining what the practice of law would look like in a world of superheroes (while usually maintaining a much more light-hearted tone than in the standard Marvel fare). The most famous, and enduring, lawyer/superhero combination is Marvel's Daredevil (Matt Murdock), whose legal career has been a defining feature since his introduction in 1964.

Of course, no one was reading Daredevil to learn about the practice of law (or at least, let's hope not). Rather, the law existed as a counterpoint. Though it would take years to be more fully developed, primarily by Brian Bendis, the conflict (or at least, contrast) between the law and vigilantism is a running theme of Daredevil. Initially, it is hampered by Lee's haphazard representation of the legal system. Not only does Matt attend law school as if it were a four-year undergraduate program right after high school, but the issue ends with Matt and his law partner Foggy agreeing that they should not take an accused murderer's case because "from the police report [Foggy} was convinced he's guilty!" (as if guilty defendants did not have the right to counsel).

In addition to being an attorney, Daredevil is also blind. Not the first blind superhero nor the last (DC's Doctor Midnight preceded him by decades), the combination of his disability with his career is a bit too on the nose ("Justice is blind"). He needs both of these details to make him stand out as a new character; the marketing for the first issue is at great pains to compare him to Spider-Man. The cover proclaims: "Remember when we introduced...Spider-Man/ Now we continue the Mighty Marvel Tradition with....Daredevil!!", while the splash page, showing Daredevil leaping against the backdrop of the cityscape, appeals to the instinct of the budding comics collector:

Remember this cover? [over a picture of the first issue of Spider-Man] If you are one of the fortunate few who bought this first copy--you probably wouldn't part with it for anything! / Now we congratulate you for having bought another prized first edition! This magazine is certain to be one of your most valued comic mag possessions in the month to come!"

Apparently, justice is also color blind

Daredevil has to be enough like Spider-Man to to capitalize on the wall-crawler's appeal, but also different enough to warrant his own series. Lee and co-creator/illustrator Bill Everett do this not only by making Matt Murdock a blind lawyer, but by giving him an origin story that mirrors Peter Parker's own. Where Peter was an unathletic bookworm, Matt was pushed into serious study by his father, developing his athletic abilities in secret. Uncle Ben was Peter's model for power and responsibility (his costumed career), while Jack Murdock was the driving force behind Matt's civilian identity.

Peter's origin contains three important turning points: gaining his powers, failing to stop a crime (and thereby inadvertently causing his uncle's death), and resolving to use his abilities for the greater good. Matt instinctively acts to prevent a tragedy, pushing a blind man out of the path of a runaway truck and losing his sight to a radioactive cylinder that hits him along the way. Since the radioactivity grants him heightened senses, the origin of his powers overlaps with the demonstration of his refusal to stand by and watch (something he will literally never be able to do again). The determination to be a costumed superhero comes when he loses his father, like Peter's loss of his Uncle Ben, but again with a twist: Peter is honoring Uncle Ben's wishes and memory, while Matt, by resorting to physical violence, is only honoring his father's wishes in the breach.

Matt's entire life is defined by this double bind: his father's injunction to avoid violence in favor of school and, eventually, a middle-class profession, and his lifelong need to act, to intervene, and to set wrongs right. As a result, Daredevil is a walking, swinging, embodiment of Lacanian theory: his actual father's explicit limitations on his individual agency turn into a neurotic manifestation of all that he is supposed to repress (his physicality, his heroism). He dons the original (hideous yellow and red) Daredevil costume in response to his father's murder, and any satisfaction gained by inadvertently causing the death of the man responsible is haunted by the fact that he is doing exactly the opposite of what his father wanted. The irony is intensified by the fact that Jack Murdock's decision not to throw the fight (despite the Fixer's instructions) is motivated by Matt's presence in the audience; Jack had strayed from his own principles, but redeemed himself for the sake of his son. Matt can never be fully redeemed; the double bind imposed by his actual father then gets transferred to his professional life: every night he patrols as Daredevil, he is violating the law he has sworn to uphold (even if it is in the name of the justice to which the law is supposed to aspire). [1]

Note

[1] Miller complicates the scenario in his retelling of Matt Murdock's origin and early years, Daredevil: The Man without Fear (illustrated by John Romita, Jr. 1993-1994). In addition to shoehorning the retcons he made during his first Daredevil run (Elektra, Stick), he includes a scene of domestic violence. Still a little boy, Matt runs home to brag to his father about winning a fight with a bully. Mike smacks him, and Matt runs away. The captions convey his thoughts: "Dad hit me. / It was wrong. / Dad was wrong. / And if even Dad can be wrong, then anybody can do bad things. Anybody at all. / The only way to stop people from being bad is to make rules. Laws. /Somewhere in a long and lonely night the boy's course is set. / He will study the rules. / He will study the laws." The narration of the scene, along with the image of Matt staring out into space, echoes the origin of the other corporate superhero on whom Miller would make his mark: Batman. But it is almost a parody, in that it is the origin not of Daredevil, but of Matt Murdock, attorney-at-law. Where Bruce Wayne swears to uphold justice as a vigilante in response to his parents' deaths, Matt Murdock resolves to study law in response to his father's violence.

Next: Punchable Villains and Billable Hours

Second(ary) World Problems

Here the gap is between earnestness and camp

It stands to reason that, as superhero comics grew more complex and skewed more adult, their ethical framework would start to wear thin. Developing out of an artistic practice of literal caricature, the early superhero comics were never intended to function as anything like a realistic representation of the world that produced them. Discussing the comics form, Scott McCloud calls cartooning "amplification through simplification," a phrase that could just as well apply to superhero comics' approach to content and theme. The Lee/Kirby/Ditko innovations of 1960s Marvel brought the genre a few steps closer in line to the "real world," but picking up any Marvel comic from, say, 1963, and reading the dialogue aloud would demonstrate that several steps still remained. This may sound like a value judgment, and to some readers and critics, it would be. My point is rather than a growing awareness and dissatisfaction with the disjuncture between the world of Marvel and DC and the proverbial "world outside your window" would push corporate comics in the direction of increased realism and, as we see in the case of the drug-themed comics of the 1970s, "relevance." Yet this "realism" ages just as quickly as do the hairstyles and clothes. An unfriendly reader will find at least as much to mock in an O'Neil/Adams "Hard Travelin' Heroes" Green Lantern / Green Arrow story as in an issue of the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four. Jumping ahead to the twenty-first century , Brian Bendis's Mamet-inflected, hypernaturalistic dialogue is another likely candidate for retrospective snark.

Certainly, there is no reason to make a fetish of realism, as though verisimilitude were the single determining criterion for assessing or enjoying a work of art. Nor is a fictional world's resemblance to the "real" world essential for making a point about justice, ethics, behavior, or metaphysics, as any number of works of fantasy demonstrate. The problem for superhero comics comes when the gap between the allegorical fantastic and the faithfully representational becomes just narrow enough that the exploration of an ethical problem cannot be satisfying according to the demands of either mode. Superhero comics can fall into the ethical equivalent of the Uncanny Valley. Here, though, the problem is not a visual depiction of something human that is still un-human enough to provoke an uncanny response, but rather a setting or exploration of an ethical problem that is neither fanciful enough to be allegorical or fabulous nor mimetic enough to feel like an adequate vehicle for tackling a significant, real-world question. Mutants can be rounded up in concentration camps in nightmarish dystopian futures as a story about the horrors of genocide, but Dr. Doom cannot stand at the ruins of the Twin Towers and shed a tear through the eye slit of his iron face mask.

As a vehicle for addressing real-world problems, these superhero comics fall into another trap: perhaps less an Uncanny Valley than an Uncanny Foggy Moor. Here the gap is between earnestness and camp. Lex Luthor, Captain America, Ultimate Captain America, Ms. Marvel, John Hawksmoor (of the Authority), Ultimate Thor, the Squadron Supreme's Nighthawk, have all been American presidents in one continuity or another. The Kingpin, Luke Cage, Green Arrow, and Mitchell Hundred (Ex Machina) have all been mayors, Iron Man has been Secretary of State, and the pre-Crisis Batgirl went from librarian to congresswoman practically overnight. Just how seriously are we supposed to take this? Batgirl's 1972 congressional campaign is another patently ridiculous attempt to portray youth culture, but later examples, such as Green Arrow's stewardship of Star City and Luke Cage's time as mayor of New York, make more of an effort at credibility. Grant Morrison's "President Superman" may well be the best compromise: he and those around him take his presidency completely seriously, but, since he comes from an alternate Earth, readers are not expected to follow the month-by-month adventures of a president who repeatedly sneaks out of the Oval Office to repel alien invaders or knock asteroids out of a path towards our planet.

That’s Congresswoman Batgirl to you, sir

When Marvel made New York City the setting for the adventures of Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and virtually every other superhero they published, it was an innovation. It made National (DC), with its Metropolis, Gotham City, Central City, and Star City, look staid and old-fashioned for its unwillingness even to pretend to be engaging with our world. Over the years, however, DC's creators and editors leaned in to the advantage of their fictional settings. The familiar adage that Metropolis is New York City by day and Gotham is New York by night made sense for Superman and Batman, and eventually allowed each of the cities to be developed in directions that would have been impossible for a believable, if fictional, New York. For a time, Metropolis was infused with future tech that made it literally the "city of tomorrow," while Gotham suffered a cataclysmic earthquake that cut it off from the rest of the world and turned it into a post-apocalyptic No Man's Land. New York would occasionally be used, but some creators instead took further advantage of the opportunity to create new fantasy cities that would have their own character and facilitate their own particular type of storytelling: when James Robinson and Tony Harris created a new Starman in the aftermath of Zero Hour, they situated him in Opal City, designed to host the mystery and nostalgia that informed the storytelling. At their best, DC's fictional cities facilitate their own chronotopes: a story in Gotham would not unfold the same way in Metropolis.

Here, as in so many other cases, Watchmen shows a possible way forward. Moore and Gibbons positively revel in the derivative nature of the world they created: as a distorted version of a commercially unsuccessful superhero universe (Charlton) that itself could credibly be called a variation on DC core concepts (the street-level hero, the god, the martial arts girl), Watchmen is more of a tertiary than secondary world. The fears that grip the population are the same as those that animated so much of the political discourse of the time: the book was serialized in 1986, the year in which it also took place, and global nuclear war was an ever-present, if low-level, possibility. But Moore and Gibbons allowed their world to be substantively changed by the presence and actions of its protagonists, with American winning the war in Vietnam and Nixon somehow still in office twelve years after his real-world resignation. The themes of Watchmen did not require the readers to accept that it took place in a reasonable facsimile of their world, but the logic behind the plot and the characters' actions did not strain credibility. Though unfolding in the medium of comics and steeped in the lore and traditions of the superhero narrative, Watchmen tapped into the kind of world-building familiar to readers of high-quality science fiction: suspending disbelieve is possible and desirable because, once the reader accepts the novum (i.e., the thing that makes the work science fiction rather than mimetic) the rest of the world falls into place. The superhero comics discussed in this chapter labor under the burden of multiple, proliferating nova, with simply too many fantastic and generally inexplicable elements to make them a believable secondary world.

The odds, then, are stacked against a corporate superhero comic adequately reflecting or representing a "real world" problem. Creators have to reckon with the limits of the permissible, which, depending on the time and circumstances, can be a matter of industry self-regulation, company policy, or the spoken and unspoken expectations about the contents of comics. The seriality of these comics could, at least in theory, work in favor of ethical exploration, but the inevitable changes in creative and editorial teams and the sheer accumulation of detail and lore (continuity) are significant, and almost inevitable, obstacles. Finally, the tension between the fantastic, sometimes campy elements of superhero comics (the costumes, the rhetoric, the tropes) and the seriousness or scale of the chosen problem is a tonal challenge that, if not insurmountable, must at the very least be daunting.

It is a historical accident that most mainstream comics make no use of lower case lettering; when the quality of printing and paper is low, the upper case is a guarantor of legibility. But it is also emblematic of the problem: regardless of subject matter or attempted tone, these comics shout at the reader at the top of their voice. One could say the same about opera--like so many aspects of medium and genre, it is as much a feature to be used as a limitation with which to grapple. Like the borders of a comics panel, the bombastic character of superhero comics is so ubiquitous as to be nearly invisible to the reader, or it can be used more playfully in a manner that one cannot help but notice. And, like the panel border, it can be all the more noticeable in its occasional absence, a reminder of what readers have come to expect without question. The corporate superhero genre functions within the invisible borders that separate it from the world that produced it, with results that are usually appreciated best when the reader has tacitly assented to the creative dissonance on which the comics rely.

Next: Chapter 3: The Law vs. Justice

Move Fast, Break Things

Resorting to brainwashing highlights the basic problem with both superheroes and this particular attempt to change the world

The use of mind control is a glaring moral failing, but it also highlights the limitations of the superhero genre. What is left for superheroes to do if there is no one else to fight? Since the Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-1951), the Man of Steel's job has been described as a "never-ending battle" (initially for "truth and justice," but by the time the show moved to television (1952-1958), it was "truth, justice, and the American way"); this is a phrase that can be applied to the superhero genre write large. Superhero stories are generally serialized; there can be no end to the battle not just because crime continues in the "real world," but because the corporate imperative to maximize profit and the public appetite for more stories makes true endings inimical to the storyworld. In attempting to solve their world's problem, the Squadron becomes the problem, not just because they are curtailing freedoms, but because the rules of the genre require that they have someone to fight.

Resorting to brainwashing also highlights the basic problem with both superheroes and this particular attempt to change the world: the Squadron is either unwilling to, or (more likely) incapable of reflecting on their own ideology. As heroes, the fought "crime," upheld the status quo, and therefore were subject to being mislead when their leaders proved corrupt. As utopian dreamers, they have not bothered to develop a theory or working model of society. They act like technocrats, and in the absence of anyone above them to provide guidance, they can only see the most obvious problems. This is one of the few points where their approach converges with that of Watchmen's utopian schemer, Adrian Veidt. Veidt prides himself in following Alexander the Great's approach to the Gordian knot: it is to be simply severed rather than unraveled. The metaphor has its appeal, but it carries with it a fundamental denial of complexity. Veidt should be smart enough to know better; the Squadron, despite the presence of scientific geniuses in their ranks, does not have the wherewithal to realize that they are leaving basic philosophical questions unasked and unanswered.

Poor Tom Thumb! He creates a totalitarian mind control device, and what is the thanks he gets from his teammate? A bigoted slur

The fundamental cluelessness of the Squadron Supreme makes them frustrating, but it an integral part in making their miniseries work, just as the book's indebtedness to continuity, while making Squadron Supreme a difficult reading experience for the uninitiated, allows it to stake a claim that Watchmen cannot. Though both books started as twelve-issue series, Watchmen deliberately departs from the traditions of serial superhero storytelling. As ambiguous as its final panel is, the book nevertheless comes to a true conclusion. Watchmen deconstructs the serial superhero comic in a format that lends itself to a beginning, middle, and end. Squadron Supreme, though telling a more or less complete story, has to address the conventions of the superhero as part of Marvel's neverending narrative flow; even the book's sequel, whose title (The Death of a Universe) promises finality still manages not to provide a true ending to the characters' adventures.

The Squadron may have started as a parody of the Justice League, but it morphed into an ongoing satire of two key elements of the superhero genre: the hero's lack of engagement with the systemic questions that frame their adventures, and the expectation that the hero will always win. The Squadron Supreme exists to lose, and to lose again and again. Were it not for the seriality of their adventures, any given Squadron Supreme story could function as the superhero equivalent of tragedy: not only does the Squadron collectively suffer from a tragic flaw (their political and philosophical naivete), but by the stories' end, the body count has reached near-Hamlet levels. The Squadron Supreme miniseries abruptly tries to change its tone in the very last panel, moving from the morgue to the delivery room for the birth of Arcanna's baby, but the shift is too little, too late. There is little room to assert that Squadron Supreme has a happy ending, or, for that matter, that the team itself has any prospect of an optimistic conclusion to any subsequent adventures. If Sophocles, instead of writing the plays that survived to our day, had written a series of Oedipus dramas that each somehow ended with the title character once again putting out his own eyes, the result would have prefigured the saga of the Squadron Supreme.

Next: Second(ary) World Problems

A Magnificent Failure

These characters are not designed to refrain from taking action, and will always choose intervention over introspection

The failure of Squadron Supreme is also its brilliance, because it is turned into a theme at various points throughout the book. This is also where Gruenwald's continuity obsession pays off: yes, we have pages of exposition and summary in the first issue, but it is in the service of establishing just how bad things have become on the Squadron's world. Despite Gruenwald's own never-ending fannish enthusiasm, Squadron Supreme excels at bringing the jaded sensibility of fan who finds that superheroes are in decline. The first issue does a remarkable job of transforming a metafictional superhero malaise into the condition of the superheroes themselves.

Defeated even before the series began, the Squadron spend much of the first issue continuing to fail. Hyperion tries to stop the team's orbital headquarters from tumbling to earth, but manages only to steer it away from populated areas. In case the reader missed the metaphor, Hyperion and his colleagues make it crystal clear:

Hyperion: Maybe it was meant to come crashing down on our heads....like everything else has come crashing down on the Squadron lately.

Whizzer: I know what you mean, pal. The satellite, the world--we've all seen better days.

It doesn’t take a giant metaphor to hit you over the head…. oh, wait

The rest of the Squadron is no better off. Power Princess, Nuke, Captain Hawk, and Arcanna try to stop a food riot, but only make things worse. Golden Archer, Lady Lark, Nighthawk, and Tom Thumb manage to put out some fires caused by exploding gas mains, but they know that similar disasters are playing out all over the country. When the Squadron finally assembles, both Hyperion and Nighthawk lament that this situation is "all our fault," with the Whizzer confirming that the rest of the world is in even worse shape than the United States. The despair is palpable, and the book is slipping dangerously away from superhero territory and into the direction of a Democratic focus group during the Trump administration.

What they need is what the best superheroes provide: inspiration. So it falls to Power Princess, the Squadron's stand-in for Wonder Woman, to argue that the heroes are thinking to small. She grew up in a utopia; why can't the Squadron turn the rest of the world into a paradise? Hyperion quickly agrees, and soon the entire Squadron votes on a "Utopia Project" that is not content with merely stopping the bad guys:

Hyperion: We should actively pursue solutions to all the word's problems---

---abolish war and crime, eliminate poverty and hunger, establish equality among all peoples, clean up the environment, cure diseases and---

---even cure death itself!"

“Right on!” “Boo, death!”

It's an astonishing leap--just three pages ago, the Squadron was whining about the hopelessness of their situation, and now they're going to put a stop to death. Only Kyle Richmond (Nighthawk), still technically the president after being controlled by the Overmind, makes an impassioned argument against the plan. [1] As the team's version of Batman, he is the sole non-superhuman in the Marvel version of what has come to be called DC's "Trinity" (Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman), so it is only right that he be the voice of the opposition. But the scene is clumsy and rushed. In the previous chapter, we saw how Moore and Gibbons used each of the Watchmencharacters to embody a philosophy (Existentialism, Objectivism), but even in the scenes that make their views most explicit (the first and only meeting of "Crimebusters" and Dr. Manhattan's final confrontation with Rorschach), they never speechify or even truly debate. But a more charitable reading of the speed with which the Squadron leaps into the utopia program points to the deficiencies of the superhero genre: these characters are simply not designed to refrain from taking action, and will always choose intervention over introspection.

In trying to think big, the Squadron Supreme (the team) displays an astonishing lack of imagination; whether or not Squadron Supreme the miniseries does as well is an open question. Their ideas are bold, to be sure, but hatched too quickly and never really thought through. Much of the plan is to transplant the idea and technology of Power Princesses homeland, Utopia Isle, in the broader world. But in its form, the plan looks more like a repetition compulsion: not only are the Squadron taking over the world (again), but the key weapon in their arsenal is also their Achilles' heel: mind control. Instead of simply fighting the bad guys, they will use advanced technology to turn them from adversaries into team mates.

At this point Squadron Supreme could have turned into a dystopian nightmare about the rise of an irresistible form of fascism, but that would have required the book to broaden its focus to the general populace. Ordinary people are only of interest to the narrative to the extent that they intersect with its super-powered protagonists: they are necessary in the first issue in order to establish how bad things have gotten, but, otherwise, they show up (less and less frequently) as the Squadron's friends and family. Small wonder that Hyperion becomes functionally blind halfway through the series; his multiple forms of advanced vision have never allowed him to perceive the most basic facts that are in plain sight. Equally ironic is the cause, a fight with his evil, extradimensional doppelganger: the Squadron is its own worst enemy.

Note

[1] Amphibian also votes against it, but, unlike Nighthawk, he agrees to defer to the will of the majority.

Next: Move Fast, Break Things

Plot Cancer

The Squadron Supreme do not just fail to save their planet; they fail to show that there is much life left in the superhero concept

If Squadron Supreme suffers in comparison to Watchmen, it is at least in part a question of each work's relationship to its own time. And this is even while making allowances for Gruenwald's preoccupation with continuity as a legitimate artistic choice. The real problem is that, despite appearing within a year of each other, they read as if their production were separated by decades. Watchmen set the standard for superhero stories going forward; for good or ill, it changed the verbal, visual, and thematic vocabulary of the genre. Squadron Supreme, by contrast, is a perfect example of how comics were made before Alan Moore's influence. Thought balloons are everywhere; the main characters tend to explain their motivations out loud, the art is unexceptional, and the minor characters are written and drawn as if they are just waiting around for the protagonists to interact with them.

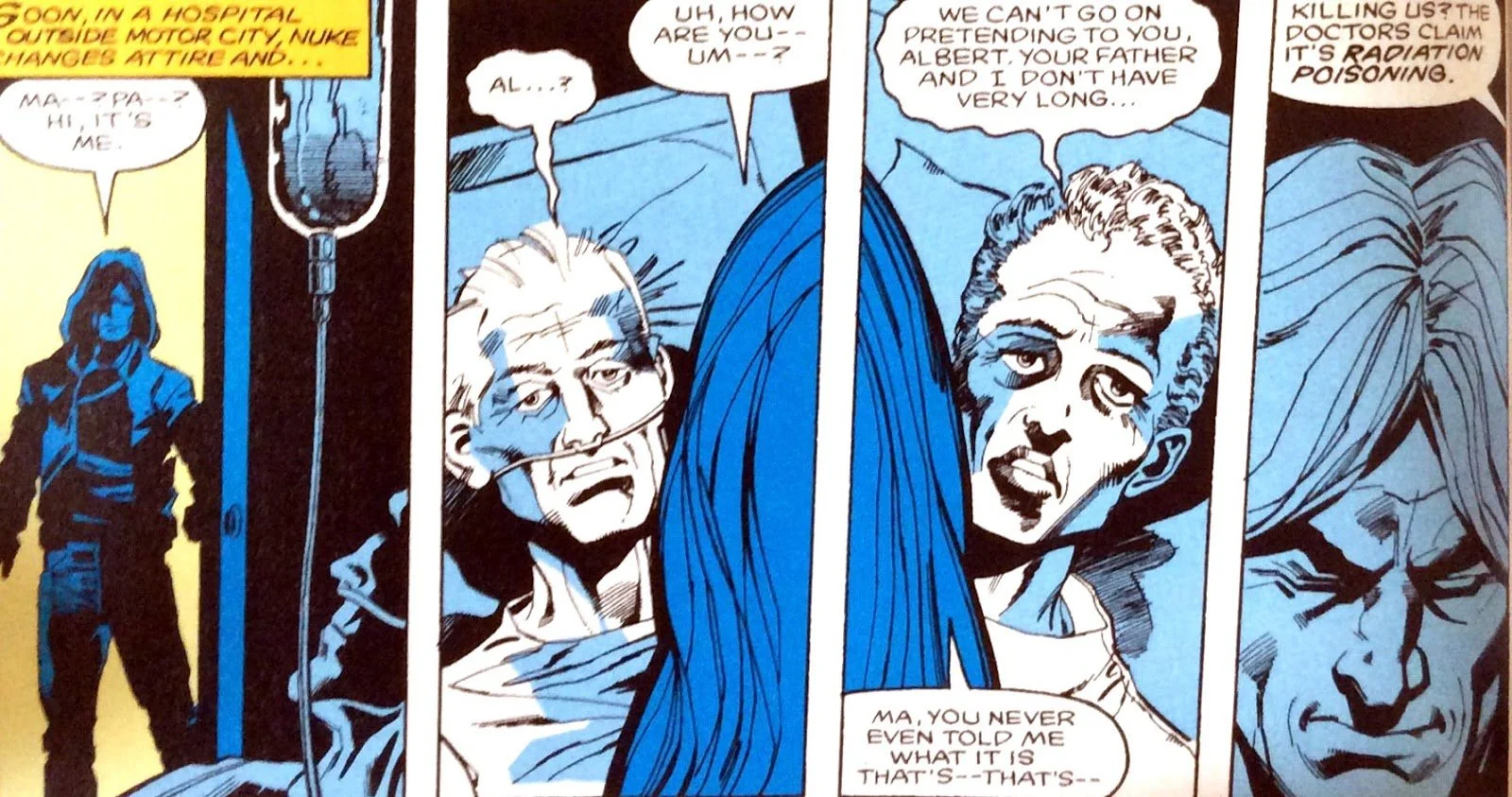

When the young hero Nuke (an analogue to DC's Firestorm) is worried about his parents, who are dying of cancer caused by exposure to his radiation, he visits them in the hospital. Dressed in identical robes and sporting near-identical short hair, his mother and father actually share a room there. As is typical in mass culture at their time, they just have "cancer" (no organ is specified, no stage is named), and when Nuke asks them about their status, his mother answers, "They want us to continue chemotherapy for a while longer, son." In other words, they function as one patient in the hospital, with one chemotherapy protocol. My point is not that this is bad medical care; nobody was reading Squadron Supreme to learn about oncology. Rather, their disease, suffering, and hospitalization only exist to the extent that they have an impact on Nuke.

Nuke's parents' cancer is not without value to the story. It is a step in the direction of "real world" problems being taken up by superhero comics, starting with the basic acknowledgment that a character whose powers are based entirely on radiation might be a danger to those around him. Their illness also raises a question that haunts the genre: if the world is populated by supergeniuses, why haven't their discoveries led to significant technological and social change? Why not use those superbrains to cure cancer? Marvel brought up the same question just three years earlier in Jim Starlin's The Death of Captain Marvel, when Rick Jones challenges Reed Richards, Hank Pym, Hank McCory and other superhero scientist to cure Mar-Vell of the disease that is killing him. In Squadron Supreme, Nuke begs resident genius Tom Thumb to work a similar miracle, setting him on a convoluted path involving an intelligent female super-ape who falls in love with him, a tyrant from the far future, and Tom's own (ironic!) death from yet another case of unspecified "cancer." The race for a cure is a dead-end; the miracle elixir Tom gets from the futuristic tyrant won't work in our time, and Nuke actually precedes Tom in death: his guilt over his parents' demise send him off the deep end, prompting a fight with his teammate Dr. Spectrum, who accidentally kills him.

As this brief summary of only a minor plot thread shows, Squadron Supreme leaves a high body count: Tom Thumb, Nuke, Nuke's parents, Golden Archer, Pinball, Nighthawk, Foxfire, Blue Eagle, Lamprey, Power Princess's husband, and Hyperion's evil counterpart from the Squadron Supreme. In addition, Ape X is comatose, and Thermite is in critical condition with a "10 percent chance of recovery." The book ends on optimistic note (Arcanna gives birth to a son), though the 1989 follow-up, Squadron Supreme: Death of A Universe dispenses with Inertia, Professor Imam, and the Overmind (don't ask), even if the book failed to deliver on the total annihilation promised by its title. The world of the Squadron Supreme kills off characters with a What If? level zeal (though at least their deaths have consequences as part of an ongoing set of stories).

No, no, no! The parents are supposed to die during the origin!

With all these caveats and complaints, and given how many other examples there are of superheroes trying to solve the world's problems, what makes Squadron Supreme worth considering? As is often the case with interesting comics that have never managed to rise to the status of universal acclaim, the flaws are as revealing as the strengths. Where Watchmen, despite its apocalyptic sensibility, charts a future for superhero comics though an unusually complex relationship to genre (simultaneously digging deeper into superhero tropes while also looking beyond them), Squadron Supreme is an exploration of the superhero as a dead end. The superheroes themselves are at a loss, turning to their utopian project out of desperation; the storytelling, which does not push the conventions of mainstream comics forward even an inch, feels particularly leaden in the context of a plot about breaking with the status quo, while at this point in publishing history, Marvel Comics, with the exception of X-Men, Thor, and Daredevil, has shown precious few signs of inspiration or innovation since Jim Shooter drove out most of the company's best talent by the end of the Seventies. The format of Squadron Supreme, a twelve-issue "maxi-series" was new for its time, but even as it experimented with publishing models throughout the Eighties, Marvel was largely conventional when it came to content. The Squadron Supreme do not just fail to save their planet; they fail to show that there is much life left in the superhero concept.

Next: A Magnificent Failure

Earth's Mightiest Punching Bags

The Squadron Supreme could always be counted on to take a bad situation and make it worse

Though it has its share of admirers, the Squadron Supreme miniseries (September 1985-August 1986) was the victim of unfortunate timing, sandwiched between two DC projects that were destined to gain the industry's attention: Crisis on Infinite Earths (April 1985-March 1986) and Watchmen (September 1986-1987). Set on an earth parallel to that of Marvel's main continuity, it shared the multiversal preoccupations of Crisis, but on a smaller scale. Like Watchmen, it reexamined the superhero's role, but in a much less nuanced fashion. And like both, it featured heroes who were variations of previously established characters: Crisis's multiple earths included multiple iterations of Superman and Batman; Watchmen was originally pitched as a story about the heroes DC had recently purchased from the defunct Charlton comics, transformed into new characters for the purpose of the story; and Squadron Supreme was a longstanding variation on DC's Justice League.

In Marvel's hands, the Squadron would always have to be in some way inferior to the Avengers; after all, the Avengers were the home team. [1] But the Squadron was more than just Marvel's answer to DC's most famous superteam; over the years, the Squadron grew from a parody or set of in-jokes into an unusual type of foil for the Avengers: not just opponents (though they were that, too), but a political cautionary tale. This would seem to be an unlikely evolution, since everything about the Squadron initially pointed inward towards hardcore comics lore, rather than outward, towards the world of the readers.

The Squadron Supreme was not even directly based on the Justice League; it was a variation on a group of supervillains introduced in Avengers 70 (November 1969) called the "Squadron Sinister." Created by Roy Thomas and Sal Buscema, the villainous squadron was an answer to that most fanboyish question, "Who would win in a fight: the Avengers or the Justice League?" The answer, of course, was predetermined; if even the Squadron Supreme would never win, a team of bad guys never had a chance. The original Squadron Sinister consisted of Doctor Spectrum (Green Lantern), Hyperion (Superman), Nighthawk (Batman) , and the Whizzer (the Flash). This team had a relatively limited impact on Marvel's main continuity; only Nighthawk became a character in an ongoing series (The Defenders) after renouncing his criminal past.

Thomas returned to the concept in Avengers 85 (February 1971), when the Avengers end up on the home world of the Squadron Supreme, a team of heroes who just happen to be identical to the villains whom they battled just over a year ago in real time. Naturally, a fight breaks out; not only does this always happen whenever two superheroes meet for the first time, but the Avengers mistake this earth's heroes for the Squadron Sinister. The Squadron Supreme only became a vehicle for political commentary when they returned for the "Serpent Crown" storyline that ran from Avengers 141 (November 1975) through Avengers 149 (July 1976), written by Steve Englehart. [2]. That this was Englehart's doing should come as no surprise; his run on Captain America (a book he had just left) included the previously-mentioned "Secret Empire" storyline whose villain was Richard Nixon in disguise. [3] Here the Squadron are reintroduced as "sell-outs" working for Roxxon, the company Marvel uses any time they need an evil corporation as a heavy (Englehart introduced Roxxon in Captain America 180 (December 1974). [4]

Face it, Tiger: you’re a loser

When the Avengers journey to the Squadron's world, they not only can see how it has gone wrong, but they are in a position to rub the Squadron's noses in it. At the end of the story, the Beast disguises himself as that world's president, Nelson Rockefeller, and tells Hyperion that his team has lost its way, and that Rockefeller's government is corrupt. The Beast's disguise is almost immediately exposed, but the truth of his words hit home. The movement back and forth between mainstream Marvel and the Squadron's world allows the political satire to be kept at one step's remove from the world of the Avengers, which, unlike the Squadron's, will not have to embark on the long work of rebuilding democracy after an oligarchical coup. But the interplay between the two dimensions also lets the satire target two different worlds: the "real world" and the one that the Squadron's is modeled on: that of DC comics. After all, while Marvel occasionally told stories of alternate worlds in the 1970s, "multiple earths" was very much a DC thing. Compared to Marvel, DC was the stolid, traditional comics company whose heroes were "squares," and who questioned the established order even less frequently than their Marvel counterparts.

Perhaps inadvertently, Englehart's reintroduction of the Squadron Supreme established a pattern for them that Kurt Busiek would finally lampshade in his Avengers/Squadron Supreme Annual '98: the Squadron is a team of weak-willed naifs who are conned again and again. To be fair, Busiek has the Avengers speculate that something about their home universe makes them unusually susceptible to mind control, and, knowing the writer's facility for making connections with previous continuity, the explanation is probably sincere. But it also doesn't take much to imagine that, after the Avengers send the Squadron back into the multiverse, they indulge in a collective eye-roll about how easy it was to make them feel better about their inability to resist a bad idea.

Such disdain would have been well-justified. In the interim between The Serpent Crown Saga and Busiek's story, the Squadron demonstrated a stunning capacity for screwing up. In a sequence of Defenders stories they turned their world into a fascist dystopia nominally run by Kyle Richmond (Nighthawk), but actually controlled by an alien entity called the Overmind (in turn the vessel for an entity called Null, the Living Darkness). Gruenwald's Squadron Supremeseries takes place in the aftermath of that particular disaster. Cleaning up after Rockefeller's corruption was one thing, but the Overmind had used the Squadron to take over the world. How could they recover from that? Gruenwald's Squadron comes up with a terrible answer: to take over the world again, but this time as good guys.

The series gets off to a slow and difficult start, with several pages of the characters recapping the events of The Defenders to each other for no one's benefit but the reader's. Unlike Watchmen, which existed in a world created entirely for the purpose of telling one specific story, Squadron Supreme was bogged down in continuity right out of the gate.[5]. But to Gruenwald, continuity was always a big part of the fun. Gruenwald's obsession not just with comics lore, but with making all the lore fit together, was over the top even by fan standards. Before becoming a professional writer, Gruenwald published a fanzine called Omniverse that was dedicated to exploring the nuances of continuity. He brought this same sensibility to his comics work, creating The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe (1982-1984), a fifteen-issue illustrated guide to the company's characters and events. His series Quasar (1989-1994) deployed his esoteric Marvel knowledge as the building blocks of storytelling; there was hardly a cosmic character who failed to at least make a cameo over the course of the series' 60 issues.

In 1988, he scripted an 11-part series of back-up stories about the High Evolutionary, a frequent Marvel antagonist whose complicated backstory was Gruenwald catnip, and, together with Ralph Macchio and Peter Gillis, he wrote a series of back-up stories in What If? centering around Jack Kirby's Eternals. Fresh off finishing off Roy Thomas' extended sequence of Thor comics that brought Kirby's characters into Marvel's main continuity, he and Macchio (and eventually, Gillis) set out to tell the characters' history in such a way that thoroughly (and permanently) integrated them with the rest of Marvel lore. The principle behind these stories appears to be narrative economy: they united three disparate hidden communities of super-powered beings into one common point of origin. The Celestials created the Eternals, and their experiments on primitive proto-humans were what inspired the Kree to develop the Inhumans (Kirby's earlier creation). Early in their history, the Eternals suffered a schism, resulting in an offshoot moving to the planet Titan, where they became the ancestors of Jim Starlin's Thanos and Eros. These were not necessarily bad ideas; in fact, they resulted in many good stories. Unfortunately, none of them were by Gruenwald, Macchio, or Gillis. [6]

Forty years later, it's easy to fault Gruenwald for the sheer nerdiness of his preoccupations, especially now that there actually is a market for comics/graphic novels that can be picked up and read on their own. While the book's entrenchment in decades of Marvel storytelling is a distinct obstacle to Squadron Supreme functioning as Marvel's Watchmen (i.e, as the book you can give to non-comics readers to show them why comics are good), we should at least be aware that we are judging the book by standards that it had no interest in meeting. Squadron Supreme was designed to reward the efforts and enthusiasm of the dedicated Marvel reader, in a fashion that required the recognition of continuity.

Even if the Squadron was composed of second-stringers derived from a Justice League template, they were a familiar Marvel fixture. It is one thing to watch an entirely new set of characters deviate from the run-of-the-mill superhero story, but it is another to see heroes you already know take over the world in order to build a utopia. As an established team on an established alternate Earth, the Squadron's actions felt far more consequential than an issue of What If? (or an "Elseworlds" story, DC's later designation for non-continuity stories about established characters (or variations on them). The Squadron's world was "real" within Marvel continuity, but not essential: it was possible and permissible to radically change their status quo without having to undo everything that happened by the story's end. In fact, this had already become the main rationale for Squadron stories starting with Englehart's Avengers: their world is supposed to be subject to radical change. And, unlike in Watchmen, the consequences could continue to be explored in subsequent stories. [7]

Notes

[1] Kurt Busiek and George Perez introduced a clever metacommentary on the home team dynamic in JLA vs. Avengers, the miniseries that could final dispense with thinly-veiled proxies of each company's rivals. Things worked better for each team in their home universe. Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely took the idea further, essentially embedding the rules of the superhero genre into the nature of DC's multiverse. In their Earth 2 graphic novel, when the Justice League tries to clean up the alternate earth dominated by their villainous counterparts (the Crime Syndicate), they discover that they simply cannot win in this other world, which exists for the triumph of evil.

[2] Issues 145 and 146 were a two-part fill-in story that had nothing to do with the ongoing plot.

[3] See my Marvel in the 1970s for an extended discussion of this storyline.

[4] Writers in the 1970s often began plotlines in one book, only to develop them on the next book they would be assigned. The Serpent Crown storyline gave Englehart the opportunity to wrap up threads from his run on Amazing Adventures (starring the Beast and featuring Patsy Walker) and Captain America.

[5] Even worse, it was continuity based on a comic not many people were reading. J.M. DeMatteis' run on The Defenders had many bright spots, but it was not exactly a bestseller. Assuming familiarity with the Squadron's last appearance would have been short-sighted.

[6] These historical stories were pleasant enough reads for the die-hard Marvel reader, but their payoff would only come later, especially when Kieron Gillen was writing The Eternals.

[7] There is some continuity that is too much even for Gruenwald. At the end of the Defenders storyline, Kyle Richmond's body is inhabited by the mind of his mainstream Marvel counterpart. The Squadron Supreme makes no mention of this fact.

[19] Or at least, unlike Watchmen as originally conceived. DC's decision to continue the franchise against Alan Moore's express wishes changed all that, but only after decades had passed in real time.

[20] Amphibian also votes against it, but, unlike Nighthawk, he agrees to defer to the will of the majority.

Next: Plot Cancer

This Is a Job for....Procedural Democracy?

The fantasy of a superhero president is tthe desire for a perfect synthesis of vigilante romanticism and democratic proceduralism

The superhero is, among other things, a fantasy about noble vigilantes who can fight crime more effectively than the representatives of our political and judicial institutions (see Chapter 3). While they are normally constrained by a generic conservatism that requires the maintenance of the status quo, mainstream superhero comics have occasionally taken the opportunity to imagine a hero who aspires to make systemic change, either from within (by running for office) or from above (by taking over entirely). Given how obsessed American culture is with celebrity, and the occasional successful celebrity candidates for office, a superhero president makes a certain amount of sense.

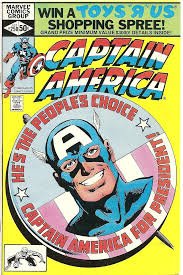

Especially after the election of former movie star Ronald Reagan. For Captain America's 250th issue, which came out four months before Reagan's victory, a team of four writers (Roger Stern, Don Perlin, Roger McKenzie, and Jim Shooter), working with artists John Byrne and Ed Hannigan, confronted the hero with a growing popular demand that he run for president. After giving it several pages of thought, Cap unsurprisingly declined to run. On the face of it, it was a very Silver Age-style idea dragged into a more sophisticated time (Captain America's identity was still a secret; how was he supposed to campaign for president?). But the explanation he gives on the final pages is a surprisingly apt summation of the problem his presidency would pose for superhero comics:

[The president] must be ready to negotiate--to compromise--24 hours a day to preserve the republic at all costs.

I understand this... I appreciate this...and I realize I need to work within such a framework. By the same token...

...I have worked and fought all my life for the growth and advancement of the American dream, and I believe that my duty to the dream would severely limit any abilities I might have to preserve the reality.

We must all live in the real world.... and sometimes that world can be pretty grim. But it is the dream...the hope...that makes the reality worth living.

The writers pose the question in terms of political process vs. idealism, but they might as well be talking about the real world vs the superhero genre. The superhero acts in a realm that rarely requires subtlety, compromise, or the dreary back-and-forth of proceduralism. Fittingly for a Captain America comic, this problem is exacerbated by the peculiarities of the American system. In a parliamentary system that grants executive power to a prime minister and ceremonial authority to a president, electing Captain America might be more feasible. But then we wouldn't be talking about Captain America or the "American dream." Still, superheroes are more compatible. with heads of states (or even figureheads) than they are with actual chief executives. [1]

Really, what could go wrong?

Captain America is not alone in flirting with the presidency; a Silver Age story has Jimmy Olsen dreaming that his pal has ascended to the oval office, while the Armageddon 2000 crossover included a possible future with the Man of Steel as president. In Final Crisis, Grant Morrison introduced DC readers to Earth 23, where a black man named Calvin Ellis is both President and secretly Superman. This "President Superman" would subsequently be brought back on multiple occasions. Mainstream DC continuity could not make room for Superman as president, but for years, Lex Luthor held that office in the DC Universe.

The fantasy of a superhero attaining the highest office in the land by means of free and fair elections is the desire for a perfect synthesis of vigilante romanticism and democratic proceduralism. In this scenario, we can keep our democratic institutions while secure in the knowledge that the man (and, let's face it, we're usually talking about a man here) at the top is not just competent and honest, but a paragon of humanity. It is the ideal fusion of the head of government, head of state, and man of steel. It is also unsustainable, not just because of hard-bitten cynicism about how politics actually work, but because the heroes who take on the country's leadership are not designed to bear such a burden with any kind of plausibility. [2]

But why should we expect a superhero to be content with the slow, demeaning process of a presidential campaign? The average superhero's career is premised on the desire to work outside the system, to cut corners, and to mete justice more effectively that any legal executive power might manage. Seizing power is a classic supervillain move; villains tend either to rob banks, murder indiscriminately, or try to take over the city/country/world, and it is usually up to the hero to stop them. Yet there is an easy homology between fighting crime as a vigilante and taking control of the government in order to improve people's lives. [Find name] draws a parallel between the detective story ("Let's solve a crime") and utopia ("Let's solve all crime"), one that easily maps onto the superhero ("Let's stop a criminal" and "Let's stop all criminals"). Beyond the question of crime, the homology is based on a disdain for institutions in the name of the very ideals that the institutions are supposed to uphold: justice (by circumventing the niceties of the justice system) and peace (by beating up those who threaten it). When the ethos of vigilantism is expanded to the scale of government, it could justify the seizure of power by well-meaning superheroes (it can also justify fascism, but that's for a later chapter).

The superhero government takeover has become such a familiar trope that it has even migrated from its comics origins to other media: the "Justice Lords" scenario on the Justice League cartoon in which a version of the Justice League take power on a parallel earth after the death of the Flash ("A Better World," Episodes 37-38, November 1, 2003). The 2013 video game Injustice: Gods Among Us, which has Superman and his allies take over the world after the Joker kills Lois Lane, launched an entire franchise (more games, multiple volumes of comics, and an animated adaptation). Compelling as these stories may be, they are based on an even more common trope: the superhero who goes bad. Though in each case, the heroes who take over claim that they are making the world a better place, the impetus is personal loss. It's a scenario that makes the heroes briefly sympathetic, but it also represents a deliberate break from one of the most common superhero origin stories. Bruce Wayne becomes Batman because his parents were killed; Peter Parker learns the lesson of great responsibility from his inadvertent role in his uncle's death. Even the original Ant-Man (Hank Pym) is motivated by the death of his first wife. With the exception of the Punisher, who started out as a response to the eye-for-an-eye ethos of the Dirty Harry movies, revenge is rarely the right path for the superhero.

Of more interest, than, are those moments when the hero or heroes make the conscious, relatively unemotional decision to solve the world's problems by taking the reins of government. This has happened on numerous occasions, but always either in a parallel world or timeline (Squadron Supreme), in a small, self-contained superhero universe (The Authority, Miracleman), or in a story destined to be reconned (Thor: The Reigning, as well as The Authority). Just as the first volume of Marvel's What If? series served primarily to remind readers that the main continuity was the best of all possible worlds, these alternate world explore forbidden scenarios as cautionary tales. It would be unrealistic to expect corporate comics to tell the story of a superhero takeover that was successful and benign; not only would this be politically unpalatable to anyone who believes in procedural democracy, as well as an implicit endorsement of fascism (no matter what the explicit policies of the superhero leaders happened to be), but it would also fall into the trap that awaits most utopias: as a plot, it is a dead end. Utopias are generally inhospitable to the development of compelling plots, since all major problems have been solved. All that's left for the reader to do is to learn about the utopian world, but the result is less like a novel and more like a tour guide. Gaiman's and Buckingham's follow-up to Alan Moore's Miracleman stories recognizes this limitation while pushing against its boundaries. At the end of Moore's run, the title character and a group of allies have created a paradise on earth after one of their former comrades tortured and murdered nearly the entire population of London. Gaiman and Buckingham were taking their time (decades, in fact, due to the problems surrounding the book's publication) to explore this new world in a series of one-short stories. [3] The world may be more or less perfect, but the adaptation of the individuals who live in it is still idiosyncratic, contingent, and not always personally satisfying. [4]

In the mid-1980s, both DC and Marvel published 12-issues limited series that featured superheroes crossing the lines in order to save the world. One of them, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen, whose plot hinged upon a brilliant former hero's decision to end the Cold War through complex subterfuge, is widely recognized as a classic in the world of graphic novels. The other, Squadron Supreme, written by Mark Gruenwald with pencils by Bob Hall, Paul Ryan, and John Buscema, is best remembered for the fact that, at Gruenwald's request, the first printing of the collected edition of the series used ink mixed with his own ashes after his premature demise.

Notes

[1] Marvel has repeatedly returned to the idea of a President Captain America, but always in stories or settings that are safely outside of mainstream continuity. Two different issues of What If? explore this possibility (What If vol 1, 26, April 1981 and What If, vol 2, 28), and not long before the Ultimate Marvel Universe was destroyed, Captain America became president of a fractured nation which he sought to unify.

[2] Exceptions are made for alternate universes and timelines, of course, but also for futures that may or may not come to pass. Marvel has repeatedly returned to the idea that Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel) will one day grow up to be president. Kamala's presidency does not strain the superhero framework as much as Superman's or Captain America's (even taking into account that she is a brown Muslim Inhuman mutant woman with weird powers), because Kamala is still a teenager. Her future presidency is a statement about her potential rather than her actuality, and is also consistent with the overall optimism of Ms. Marvel's own comics. In addition, the progressive character of Kamala's successful presidential bid (again, brown, female, Muslim, mutant, Inhuman) counterbalances the populist and even fascist overtones of electing a superhero.

[3] The rights to the character now best known as MIracleman are a saga until itself. The character was created by Mick Anglo after his British publisher lost the rights to reprint Fawcett's Captain Marvel (who is now best known as "Shazam"). To replace the Marvel family, Anglo barely changed them: Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel, Jr.l became Marvelman and Young Marvelman. In the 1980s, Dez Skinn hired Alan Moore to revive the character for his new Warrior anthology. Moore completely revamped the character, turning it into the first of many deconstructions of the superhero archetype. When the stories were reprinted in the United States by Eclipse Comics, the name was changed to "Miracleman" to avoid lawsuits from Marvel Comics. Moore completed the story he planned and turned the book over to Gaiman. Gaiman and Buckingham produced eight issues of Miracleman from 1990-1991. Moore also gave Gaiman the rights when Eclipse collapse. However, Todd McFarlane purchased Eclipse's assets and claimed ownership to Miracleman. Lawsuits ensued, until it was discovered that Anglo was still alive and owned the rights. Marvel purchased the license from him 2009 and began reprinting the series, but only started publishing new material by Gaiman and Buckingham in 2022. Thus the gap between their first run on the book and its revival was 31 years. Subsequently, the allegations that Gaiman assaulted several women put an end to the Miracleman revival.

[4] At the same time, they are also setting up a major challenge to the new status quo that will probable lead to its downfall.

Next: Earth's Mightiest Punching Bags

Crisis at the World Trade Center

It is only a short step from "Would Dr. Doom cry over 9/11?" back to, "Who would win in a fight, the Hulk or Thor?"

Perhaps the problem with these superheroic interventions is not just that the tasks are too great (even if they are); perhaps the insertion of these costume-clad figures of fantasy into an event that is actually happening is either simply in too poor taste, or too jarring to take seriously. When Dr. Doom stood at Ground Zero in the J. Michael Straczynski and John Romita Jr. special issue of Spider-Man that came out immediately after 9/11 (Issue 36), the tears welling in his eyes were not only ludicrous, but led to ludicrous fan discussions. Putting a crying supervillain in this situation is, at minimum, tacky, but it also breaks the frame in an unproductive manner. Fans and critics online repeatedly pointed out the absurdity of this moment; why would Dr. Doom, who has killed countless people and destroyed his fair share of major cities, care at all about this? This is a sensible objection, but it is also symptomatic: with a single panel, the creative team got people to expend their mental energy on the possible reactions of a comic book supervillain to a real-life tragedy that had just happened. It is only a short step from "Would Dr. Doom cry over 9/11?" back to, "Who would win in a fight, the Hulk or Thor?"

Dr. Doom’s heart grew two sizes on 9/11

Even more than the Ethiopian famine, 9/11 is a case study in the incompatibility of superhero comics with real-world disasters; in Marvel comics, at least, 9/11 would have happened in the city that is home to nearly all the company's heroes. By "incompatibility," I do not mean to suggest that superhero comics cannot be serious or weighty, or legitimate works of politically-inflected art. It is a question of genre, tone, and believability. This is not exclusively a problem of superhero comics; when HBO's Sex and the City returned after September 11, the iconic shot of the Twin Towers was removed from the opening credits, but the producers wisely declined to make a "very special episode" about the event. Executive producer Michael Patrick King was adamant that "the series should provide escapist pleasures, not debates about bin Laden over brunch." Even though the series took place in "the City," it did not have a way to address 9/11 adequately without becoming an entirely different show.

Of course, no one expected Carrie Bradshaw and her friends to actually do something about bin Laden, or to provide disaster relief at Ground Zero. Superheroes, on the other hand, should be expected to do precisely that. Which was the problem with Amazing Spider-Man 36 in particular and superhero comics involving 9/11 in general. Just how many times have superheroes foiled terrorists and stopped airplanes from crashing? How many buildings have they saved from total destruction? The only reason Marvel or DC superheroes would be unable to save the Twin Towers is that, in our world, they were not saved. Even setting aside the heroes' inexplicable failure, there is the question of continuity and tone. Entire cities have been destroyed in mainstream superhero comics, but with limited consequences. When Green Lantern Hal Jordan's home town of Coast City is erased from the map, it sets him down the path of villainy, leading him to commit mass murder and try to reboot the timeline, but the rest of the country moves on rather quickly. Coast City's destruction is only referenced when it is useful for the plot. Even worse, nearly everything about this tragedy is undone by later events; Hal was possessed by a fear entity called Parallax (don't ask), and Coast City is eventually rebuilt (although the original population remains dead). There is too much casual destruction and megadeaths in superhero comics for 9/11 to resonate properly.

Or at least as a current event and a recent trauma. With the passage of time, 9/11 can become one of many horrible historic events that is assumed to have happened in the superhero comic's past, making it available as a referent. Brian Vaughn and Tony Harris strike a delicate balance by making 9/11 a central part of the backstory to their WIldStorm comic Ex Machina (2004-2010), and it works because of the total control they have over their particular storyworld. Ex Machina takes place in a New York that has always had the same superhero comics we have, but no actual superheroes. The protagonist, Mitchell Hundred, is the newly-elected mayor of New York City who had a brief period as his world's only superhero, the Great Machine. Three years before the comic beings, Hundred used his ability to communicate with technology in order to prevent one of the planes from hitting the World Trade Center. As a result, one of the towers still stands, many lives were saved, and Hundred is able to capitalize on his newfound celebrity to successfully run for office. But Ex Machina is set in an alternate universe, where Hundred, the forces behind the events that gave him his powers, and the partial prevention of 9/11 are the only crucial differences from our own world.[5] In the absence of the daily superhero attacks and mass destruction that menace cities in DC and Marvel comics, Vaughn and Harris have created a space in which a superhero comic can reasonably address the 9/11 attacks.

From World War II to the Ethiopian famine to 9/11, the common element of all these representational failures is literalism. Literalism has never been the superhero genre's strong point; on the contrary, literalism is (figuratively) superhero kryptonite. It is the thematic equivalent of one of the many useful formal observations made by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics. McCloud shows the broad range of representational styles available to the comics artist, from the extremely cartoonish on one end to the photorealistic on the other. The cartoonish figure is stripped down and iconic, with only a few lines needed in order to create a recognizable, and even unique face (like Charlie Brown). The photorealist tries to represent the human figure as accurately as possible, something few comics artists actually attempt (the 70s art of Neal Adams, while still relying on a great deal of caricature, comes close, as does the art of Alex Ross). McCloud argues that the cartoonish representation takes advantage of what he calls the masking effect: by avoiding excessive realism, it allows readers to project themselves onto the characters, to "be" them while reading. Realistic drawing, instead of encouraging identification, turns characters into objects to be looked at. [1]

By the same token, superhero comics that are explicitly about a recent, consequential event run the risk of either getting bogged down in extraneous detail, or getting the details wrong. Superhero comics successfully comment on current events by doing what superhero comics do best: operating in the realm of metaphor. Steve Englehart and Sal Buscema's classic Secret Empire storyline in Captain America 169-175 (January-July 1974) was transparently about Watergate, but without pitting Steve Rogers against G. Gordon Liddy, or meeting with Deep Throat in a garage. [2] At both Marvel and DC, there is a long tradition of publishing stories that comment on current events and hot-button political issues by transposing them into the superhero universe. In some cases, it is a matter of the themes that are embedded into the books themselves: the X-Men franchise has always been a useful vehicle for examining xenophobia, racism, homophobia, and generalized intolerance thanks to the flexibility of the mutant metaphor. Tellingly, it is when the basis for the metaphor is made more explicit that it starts to fail: assertions that Magneto is the Malcolm X to Professor Xavier's Martin Luther King practically beg to be refuted. It does not take a deep knowledge of history or even a highly developed racial sensitivity to realize that comparing Malcolm X to a (sometimes reformed) terrorist and mass murderer is problematic. But the flaw in the comparison is not a problem with the X-Men's storytelling; there is no reason why a fantasy scenario cannot involve a leader who makes compelling separatist arguments while also committing murder. The problem is equating him with a real-life historical figure who committed no such crimes.

Marvel has doubled down on its politically-inflected storyline in the twenty-first century. Civil War can be read as a response to the Patriot Act, Civil War II as an (overly) extended interrogation of profiling, and (the second) Secret Empire as a reflection of anxieties about the rise of fascism over the past decade. But again, they work because their approach to these questions is not literal. As cathartic as it might be to see Captain America punch Donald Trump in the face, it would make little sense as a comic and be of minimal political value. Moreover, the vagaries of comicbook time mean that every instance that fixes a hero or an event in a particular historical moment will cause continuity troubles down the line, from Batwoman being discharged from the military under the "Don't Ask/Don't Tell" policy to the Fantastic Four trying to beat the "commies" to the moon. Curiously, even the solutions to these continuity problems end up serving as comments on American politics at the same time that the move the comics away from actual political events. A number of Marvel characters had the Vietnam was as an important part of their backstories, from Tony Stark's capture by the Viet Cong to the Punisher's time fighting in the war. Marvel's solution has been to move all Vietnam-related personal histories to the fictional country of Sin-Cong. Sin-Cong itself has Marvel roots that are long, but not deep; it was introduced in an issue of The Avengers in 1965, and mostly forgotten for decades. Now the assumption is that at any point in the recent past, Marvel's America was involved in a foreign adventure in Sin-Cong, which can account for all the previous Vietnam- and Korea-related origins (and, in a pinch for World War II). Is there a better summation of American foreign policy than blithely assuming that at any given point, the U.S. can be assumed to be bogged down in an ill-advised foreign adventure?

Notes

[1] Overly realistic comics art can be so distracting as to make the comic seem less real, something most obvious in comics based on movies or television series; the Gold Key Star Trek comics (1967-1979) try so hard to render the actors recognizable that the result feels stiff and posed. By contrast, Georges Jeanty's art on Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight works brilliantly because he manages to distill the characters' look without working too hard to draw the actors. The star of his comic was identifiably Buffy, but she was not Sarah Michele Gellar.

[2] The metaphor almost breaks when the leader of the Secret Empire turns out to be Richard Nixon, but, critically, he is never actually shown or named.

Next: This Is a Job for....Procedural Democracy?

We Are the World (of DC and Marvel)

The insertion of these costume-clad figures into an event that is actually happening is either simply in too poor taste, or too jarring, to take seriously

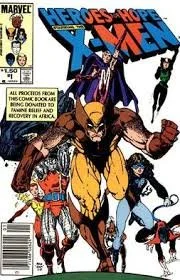

Occasionally, both DC and Marvel would bring out a special, out-of-continuity comic in which the heroes addressed a contemporary disaster, with sales going towards disaster relief. The goals were noble, but the aesthetic results were, well, disastrous. Particularly egregious were two comics put out by Marvel and DC in response to the mid-1980s famine in Ethiopia: Heroes for Hope (Marvel, 1985) Heroes against Hunger (1986). It feels somewhat churlish to lambast comics created by the combined efforts of over forty different writers and artist (for each) on aesthetic grounds; this was hardly the recipe for creating the comics equivalent of Citizen Kane. And did anyone really think that USA for Africa's 1985 charity single "We Are the World," which somehow had to accommodate everyone from Dionne Warwick to Bob Dylan (while leaving room for Dan Ackroyd and Willie Nelson) was God's gift to music? This is the sort of creation-by-committee that, when combined with a tight deadline and a seriousness of purpose that lends to stultifying piety, can at best aspire for mediocrity. It was as a mediocrity that "We Are the World" succeeded--it is an inoffensive, vaguely catchy pop tune that did the job it set out to do (raising more than $63 million in humanitarian aid). Unfortunately, neither DC's nor Marvel's efforts in this regard managed to rise above the level of the awful.

On his late, lamented web site The Middle Spaces, Osvaldo Oyola posted a scathing (and hilarious) indictment of both companies' charity comics. In particular, he takes each of them to task for their unadulterated Orientalism, beginning with the reduction of an entire continent to an "Africa" consisting exclusively of arid, famine-stricken deserts (the Marvel comic doesn't even specify Ethiopia), continuing through a level of casual racism and sexism that led Oxfam to refuse to work with Marvel on the project, and ending with the way in which each book reinforces a sense of fatalism and hopelessness about "Africa" even as they call for monetary assistance.. Oyola's article stands perfectly well on its own; for our purposes, though, it is worth looking specifically at the question of superhero involvement in "real-world" problems, and in that regard, I would only add that Oyola's criticism of the comics applies so well to Eighties rhetoric of African relief that these comics are actually an accurate representation of an important aspect of the world that produced them. This would then be the only thing about their combination of superheroes and the real world that really holds together.

Well, that, and the useful reminder that while teamwork is admirable among superheroes, writing and drawing by committee can bring on a crisis of infinite pedestrianism. DC's Heroes against Hunger was plotted by Jim Starlin (with an assist from Bernie Wrightson), and features an unlikely team-up of (pre-Crisis) Superman, Batman and Lex Luthor as they try to save "Africa" from starvation. As Oyola notes, there are some gestures in the direction of real-world politics, mostly put in the mouth of a foreign aid worker, but the comics fails both as a superhero story and as a real-world inspiration. Early on, Superman has to admit that he can't refresh the entire continent's topsoil by himself, acre by acre; soon, he and Batman discover that an alien called "The Master" has secreted himself underground to feed on the "entropy" resulting from African suffering. They can defeat him (not that much in the story would make us care about him), but they remain helpless in the face of famine. Even visually, the comics reminds us of the book's shaky underpinnings: Superman's and Batman's full-body spandex outfits, and Luthor's purple-green armor, have no place in panels surrounded by admittedly stereotypical images of starving Africans.

Marvel's Heroes for Hope had one thing going for it: rather than spend time explaining why a particular set of individual characters was involved (as DC did), it focused on their biggest hit, the X-Men, and was co-written and co-edited by the two people most embedded in the franchise at the time: writer Chris Claremont and writer and editor Ann Nocenti. [1] The X-Men were better suited for this sort of thing than most characters, since their remit usually included the exploration of xenophobia, guilt, and redemption. One of its leads, Ororo (Storm) spent years living as a "goddess" in Kenya; another, Magneto, is both a Holocaust survivor and reformed terrorist/freedom fighter/mass murder; and a third, Rachel Summers, grew up in a dystopian timeline in which the mutants who survived genocide were enslaved, and in which she had been brainwashed to hunt down fellow mutants who tried to escape. Suffering, high death rates, and tragedy were baked in to the franchise.

Don’t worry, Africa! We’re here to save you!

And yet it could never work. Even if we set aside the tone-deafness, misery porn, and casual racism Oyola rightfully condemns, the problem remains that this is a superhero comic, and superhero comics need villains and fight scenes. Even for the most praiseworthy of causes, no one wants to read 48 pages of superheroes distributing food and medicine or lobbying congress. So instead they face the allegorical embodiment of famine, at times referred to as "Hungry," who arranges psychodrama set pieces for each of the individual X-Men before taking over Rogue's body and become a grotesque, tentacled monster for the X-Men to physically fight and temporarily defeat. Along the way, many stirring speeches are given, lessons are learned, and nothing really changes.

Note

[1] Bernie Wrightson, Jim Starlin and Jim Shooter are also given a "story by" credit at the top of the page, along with Claremont and Nocenti. Sixteen other writers are credited with specific pages.

Next: Crisis at the World Trade Center

Drugs Are Bad, m'kay?

What is a superhero supposed to do about heroin addiction--punch it in the face and throw it in jail?

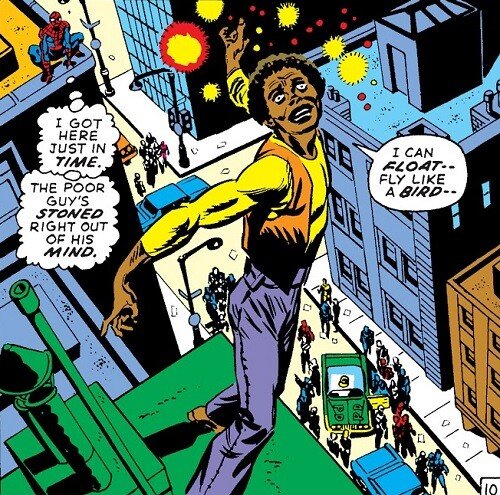

"Relevant" superhero comics also tried to address the question of illegal drugs. This proved to be a problem, because the Comics Code would not allow any depiction of drug use, even for the purposes of condemning it. Stan Lee and Gil Kane insisted on publishing a Spider-Man story involving a pill-popping Harry Osborne (Amazing Spider-Man 96-98, May-July 1971), while O'Neil and Adams revealed that Roy Harper who fought at Green Arrow's side as Speedy (!), was a heroin addict in two Very Special Issues called "Snowbirds Don't Fly!" (Green Lantern/Green Arrow 85-86, August-November 1971). These issues are celebrated for forcing the Comics Code Authority to relax a number of its policies (thereby ushering in an era of innovation in the 1970s), but as stories, they are more instructive in their failings. Both drug abuse and racism make for poor super-villains. What is a superhero supposed to do about heroin addiction--punch it in the face and throw it in jail?

You will believe a man can fly