Marvel Comics in the 1980s

Casting out the Ghost

Is this a satisfactory resolution to Rogue's trauma and overall psychological troubles? Not in the least

But sustained human contact is far in Rogue's future (even this particular encounter with Storm ends in disaster, through no fault of her own). Throughout Claremont's initial run on the X-Men, Rogue, on top of every other horrible aspect of her predicament, is a teenage virgin doomed to isolation and celibacy, sharing headspace with a grown woman who has the memories and feelings associated with the presumably active and fulfilling sex life that Rogue thinks she can never have. When Carol manifests again, this time entirely taking over Rogue's body with her assent, it is in a scenario that once again involves rescuing a man with whom Carol shares a past (Wolverine), but also echoes Carol's own experience with sexual assault.

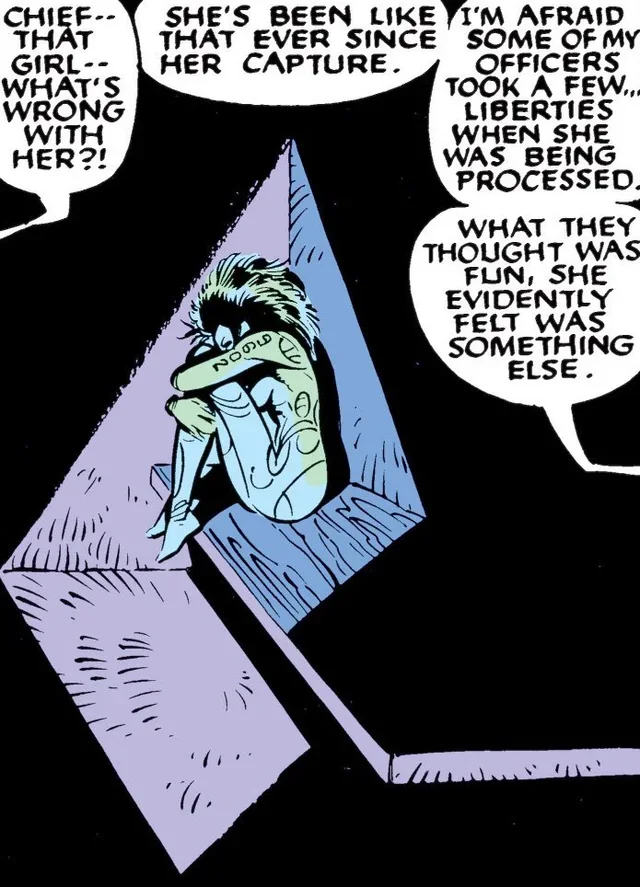

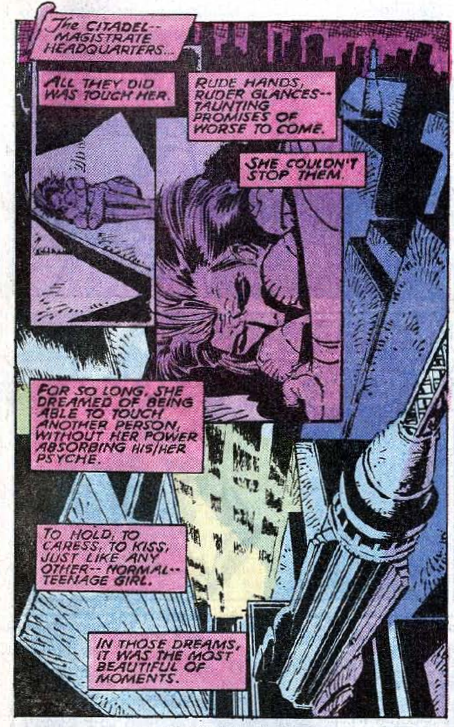

In Uncanny X-Men 236 (Chris Claremont and Marc Silvestri), the X-Men have invaded the authoritarian island nation of Genosha, where mutants are enslaved and transformed in the interest of the country's prosperity. In the course of the battle, Rogue is de-powered and imprisoned. She is also treated roughly by the guards, and Claremont's narration makes clear just how traumatic this is for her:

All they did was touch her.

Rude hands, ruder glances---taunting promises of worse to come.

She couldn't stop them,

For so long, she dreamed of being able to touch another person without her power absorbing his/her psyche.

To hold, to caress, to kiss, just like any other--normal--teenage girl.

In those dreams, it was the most beautiful of moments.

She never imagined being handled against her will.

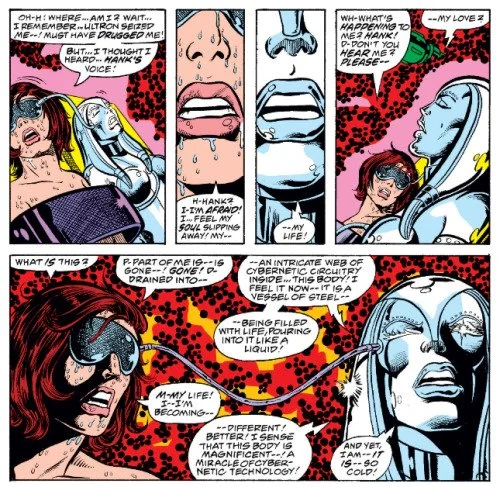

Rogue withdraws from the world, trapped in her own psyche. [1] Her mind reacts to the assault by confronting her with all the psychic residues other people she has ever touched (and whose psyches she has absorbed); they all want a piece of her. The only thing standing in their way is...Ms. Marvel. She, of course, is more than a residue, and she offers her help out of enlightened self-interest (they share a body, after all). Rogue must agree to let her take over, and to trust that Carol will yield control later. It makes sense that she is able to cope with what Rogue cannot: she is a mature adult with more life experience, including surviving trauma of her own (i.e., Marcus). After the fight is over, she and Rogue seem to have reached an accommodation, with Carol taking over now and then when Rogue is in pain. Their detente is remarkable, but also consistent with one of Claremont's ongoing themes: the power of female solidarity.

It is also short-lived. Even during the Genosha adventure, Uncanny X-Men was gearing up for a huge crossover, Inferno, which would be the culmination of years worth of plotlines, none of which featured Rogue very strongly. This was the third such crossover in just over three years, following The Mutant Massacre and Fall of the Mutants, the second of which had set up a new status quo for the X-Men. Now believed dead, they worked out of Australia, but had access to the entire world thanks to the aid of the silent Aborigine mutant Gateway, who could teleport them wherever they wanted to go. Inferno aside, Uncanny X-Men was somewhat rudderless, alternating between the main X-Men in Australia and a group of second-stringers possessed by the Shadow King on Moira MacTaggart's Muir Island.

Two years after Inferno, Claremont uses the convenient magical device called the Siege Perilous to reset the X-Men. The Siege had been given to them by the goddess Roma as the gateway to a second chance if things worked out poorly for them in Australia. Through a complicated set of circumstances, the X-Men go through the Seige, most of them starting new lives, with only Rogue seeming to pick up more or less where she left off. Uncanny X-Men 269 ("Rogue Redux" by Claremont and Jim Lee) follows Rogue after the Siege has done its work on her. Back in Australia, she is suddenly confronted by Ms. Marvel, apparently back in an independently functioning body, while Rogue discovers she no longer has Carol's old powers.

It is thus implied that the Siege has done its work as a "get out of jail free" card for Rogue after all. Instead of removing her memory (as it does with Colossus), or putting her in a situation where she can be brainwashed and have her mind transplanted into the body of a Japanese ninja (Psylocke; don't ask), Rogue gets to be truly herself, with Ms. Marvel as a ghost rattling insider her consciousness.. Unfortunately, only one of their bodies can survive. Even less fortunately, Ms. Marvel finds herself a captive of the X-Men team enslaved by the Shadow King on Muir Island, Now when Ms. Marvel finds Rogue again, not only is her body falling apart, but she is throughly evil and bloodthirsty. This circumstance (which really does come out of left field) removes the moral ambiguity in the fight between these two women; for once, Rogue is not the aggressor, and Ms. Marvel is the villain. Even here, though, Rogue is spared further moral compromise: the killing blow comes not from her, but from Magneto (moral compromise's poster boy in the X-Men's world).

Is this a satisfactory resolution to Rogue's trauma and overall psychological troubles? Not in the least. It is, however, entirely consistent with the Siege Perilous as a plot device. The Siege allows Claremont to reset any scenario that has become too tedious (as the Australian years certainly had). Part of that reset is to bring down the overall level of trauma to a more manageable scale. The moment when Roma gives the Siege to the X-Men is its own moment of reset. It's not just that the X-Men have all died and come back to life in their fight against the Adversary--for the X-Men, dying and coming back to life is an ordinary Wednesday. Nearly all of them had been stuck on a darker path since the Inferno event, and were wearing their trauma on their sleeve: Ororo had only just regained her powers after more than three years real time; Madelyne Pryor had lost her husband to his first love, her baby to unknown kidnappers, and her life to the same enemies who faked her death; and Dazzler had had Destiny's golden mask fused to her face with a magical dagger that remained protruding from her forehead. The reset was a gift to both the characters and the writers.

The abrupt disappearance of Carol Danvers from Rogue's does not turn out to be a guarantee of happiness and mental stability, but it does allow Rogue to develop as a character in ways that are no longer dependent on her dual selves. Over the next decades, she will grow more confident, both professionally and romantically, even leading a joint team of X-Men and Avengers. The fact that new writers inevitably re-traumatize Rogue (usually through the use of her powers) could be seen as a lack of imagination, but a more charitable reading is that Rogue, as a character, allows for the possibility of real psychological progress while never succumbing to the illusion of a permanent cure.

Note

[1] Claremont is curiously fond of this motif. Professor Xavier, Gabrielle Haller, Emma Frost, and Magneto have all suffered a similar affliction.

Next: Daughter from Another Mother

The Three Faces of Rogue

The former Ms. Marvel's terrible loss is Rogue's unbearable excess

In Rogue, Claremont finds the perfect vehicle for so many of his preoccupations: trauma, certainly, but also duality: when Jean Grey says that part of her wants one thing, while another part wants something different, she may be speaking metaphorically (though she may also be speaking about the Phoenix Force), but Rogue is actually trying to cope with having two different people inside her head. While at times this can look like Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), there is a crucial difference. A person with DID develops alters in response to trauma, but these alters stem from the core self. Rogue's "alter" not only did not come from within herself; she is a completely different person with her own life experiences. Moreover, the Carol persona is the source of trauma rather than a mechanism for defense. Carol is the trauma, and, as a continued presence in Rogue's head, she is trauma as an ongoing process. She is also a constant reminder of Rogue's own guilty: Carol's presence as a source of emotional pain is simultaneous the absence that torments the original Carol Danvers. The former Ms. Marvel's terrible loss is Rogue's unbearable excess.

Throughout the first few years of Rogue's presence on the team, Claremont uses Carol's spectral presence sparingly. When she first explains her problem in Uncanny X-Men 171, we only have her description of her personality problem, rather than a direct representation of her experience. Most of the time, Rogue's psychological troubles manifest through her fear of physical contact and concomitant sense of isolation. But on three significant occasions, Carol's persona takes center stage.

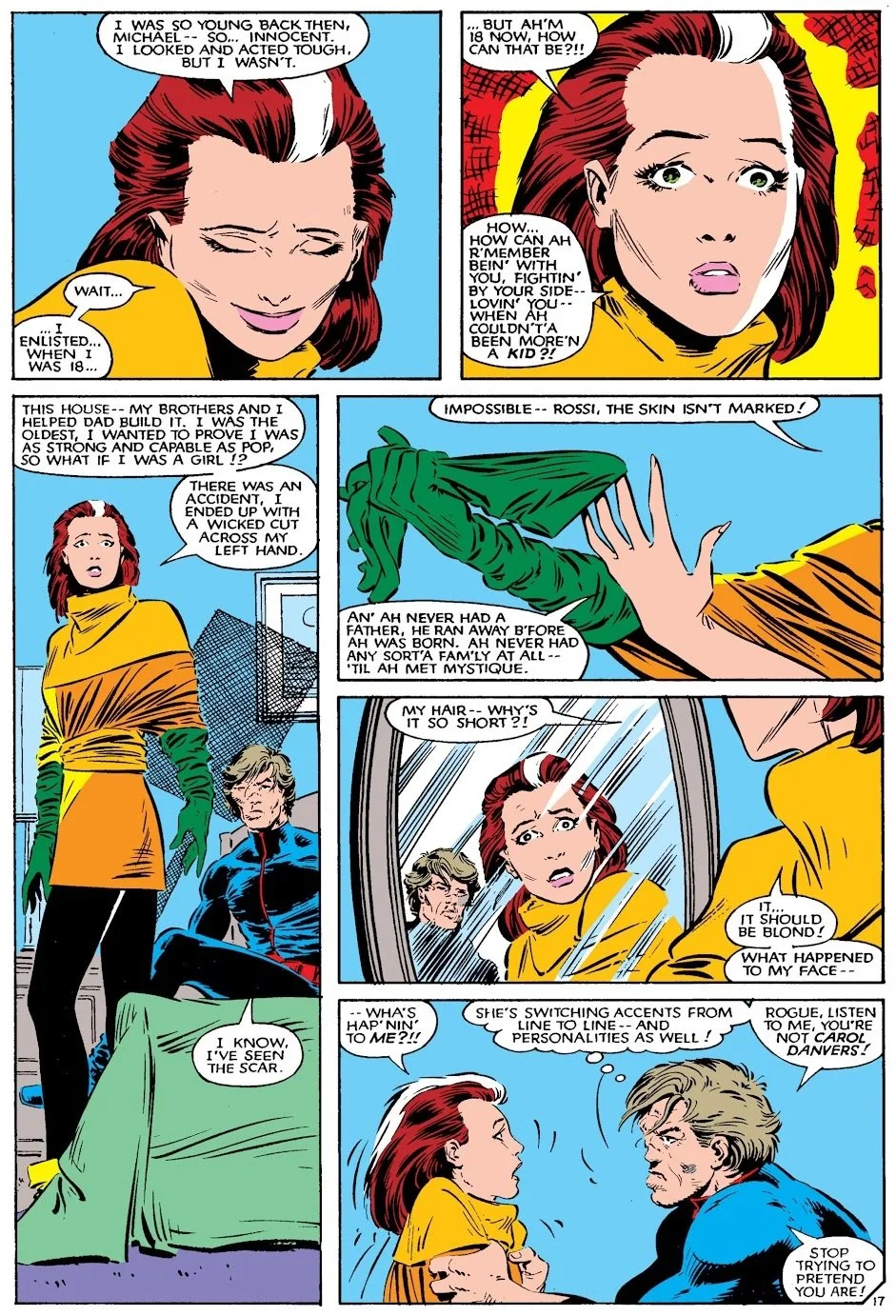

Nearly a year after she joins the X-Men, "Madness" (Uncanny X-Men 182, with art by John Romita Jr and Dan Green) starts out as a solo Rogue story before demonstrating the impossibility of the idea: Rogue is never really solo. The issue begins on an unusually carefree note for Rogue, as she flies back to Westchester from Japan (where the X-Men were teleported at the end of the first Secret Wars event). But she is also exhausted, and her guard is down. When she hears a voicemail from Michael Rossi, Carol's former espionage partner and lover, she flies off to rescue a man whom she has never actually met. As she breaks her way into the helicarrier where he is held captive, she still thinks and acts like Rogue, until she catches sight of the injured Rossi. Without realizing it, she immediately takes on Carol's voice and Boston accent, not to mention her life experience, telling him: "Me and the bad penny, lover, forever popping up where and when least expected."

The rest of the issue is a two-person psychodrama--three, if we count not just Rogue and Rossi, but Carol. What makes it all so compelling is the lack of clear boundaries between Rogue and Carol. Rogue is dissociating, and there are moments when she seems to be speaking entirely in one voice or the other, but they appear to be experiencing "co-consciousness;" rather than blacking out and being unaware of what happens, "Rogue" and "Carol" are this point different modes adopted by the body's core self. She reacts to Rossi with Carol's love, memories, and attitudes, but her own body reminds her that she is Rogue (she lacks Carol's scars and is much younger). Fleeing the house where she has brought Rossi to recover, Rogue briefly experiences Carol's childhood, which brings her fleeting moments of happiness, but soon her tour of Carol's life forces her to re-experience the core trauma of her assault on Ms. Marvel, this time from both sides. This is the essence of her torture: she is always Rogue, guilty for her actions and suffering the consequences, and she is also always Carol, an entirely different woman whose emotional life is available only to Rogue. She tells Rossi, "Ah'm Carol--in all the ways that counts!" but Rossi rejects her: "I wish there was some way to make you pay for what you've done. / I wish I had the power to kill you." Rogue's response is perfect: "So do I, my love. / So do I." Her Southern accent is missing; she is speaking in Carol's voice, for both of them.

It makes sense that the contrast between the eighteen-year-old Rogue and the thirtysomething Carol comes to a head during an encounter with a man Carol loved. Though Rogue is repeatedly depicted as sensual and playful (basking in male attention while wearing a bikini in Uncanny X-Men 185 ("Public Enemy!", with art by John Romita, Jr and Dan Green)), her powers render impossible the kind of intimacy that is so central to the memories and emotions of the more mature Carol. Any skin-to-skin contact initiates the transfer of abilities, thoughts, and feelings, but again and again, Rogue activates her powers by kissing. A twenty-first century reader might find this disturbingly non-consensual, but that is in keeping with the nature of Rogue's mutation: consent is rarely involved.

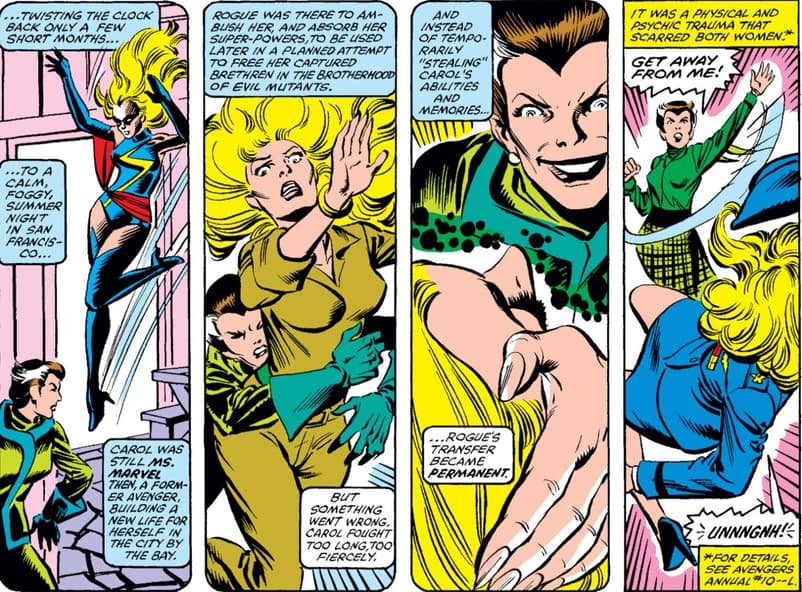

Her first playful, romantic encounter with a boy was also the first time her powers activated, leaving him comatose; kissing as a weapon is a reenactment of the adolescent trauma her mutation caused her. It is also one of the few moments that she can experience the physical contact she has been denied since puberty. Her bungled attack on Ms. Marvel, then, could easily be understood as a metaphor for sexual assault, were it not for the fact that the entire episode was part of Claremont's attempt to recover the character after the assault on her in Avengers 200. When Carol regains consciousness and selfhood with the aid of Professor Xavier, it is the Avengers she needs to confront, not Rogue. Their actions were a betrayal of trust and friendship; Rogue was an opponent she barely knew.

During a heartfelt conversation between Rogue and Storm in "Public Enemy!" (showing just how much progress the two have made with each other since Storm's initial declaration that she would leave the X-Men if Rogue were inducted), Storm realizes for the first time exactly how closed off Rogue has been: "Rogue--has every exercise of your power been an act of violence? Has no one ever given himself of his own free will?" Ororo lets Rogue take her hand and experience her world without resisting, and it is a revelation. Though the contact is not explicitly sexual, it is certainly consistent with Claremont's long-running lesbian subtexts (Storm and Yukio, for instance), and it offers a small bit of hope that Rogue can find a way to make real human contact.

Next: Casting out the Ghost

Going Rogue

"Rogue" packs in more trauma per panel than any other X-Men story to date

Exactly a year after Avengers 200 sent Carol off to Limbo, Avengers Annual 10 (written by Claremont, with Michael Golden on pencils) brought her back in a story aptly titled "By Friends---Betrayed!" Claremont's response to the original story, which left no room for Carol's subjectivity (or even her basic feelings), was to lean into that basic denial of selfhood. When Spider-Woman rescues a mysterious blonde woman thrown off the Golden Gate Bridge, it takes some time to identify her as Carol Danvers, and even longer as Ms. Marvel. Her mind has been completely erased; it is only with the help of Charles Xavier does she get most of her memories back. Xavier, as Claremont's surrogate, literally rebuilds her character. During a fight with Rogue, the two were in physical contact for too long. Normally, Rogue's absorption of powers and memories lasts a limited time, but now the transfer is permanent.

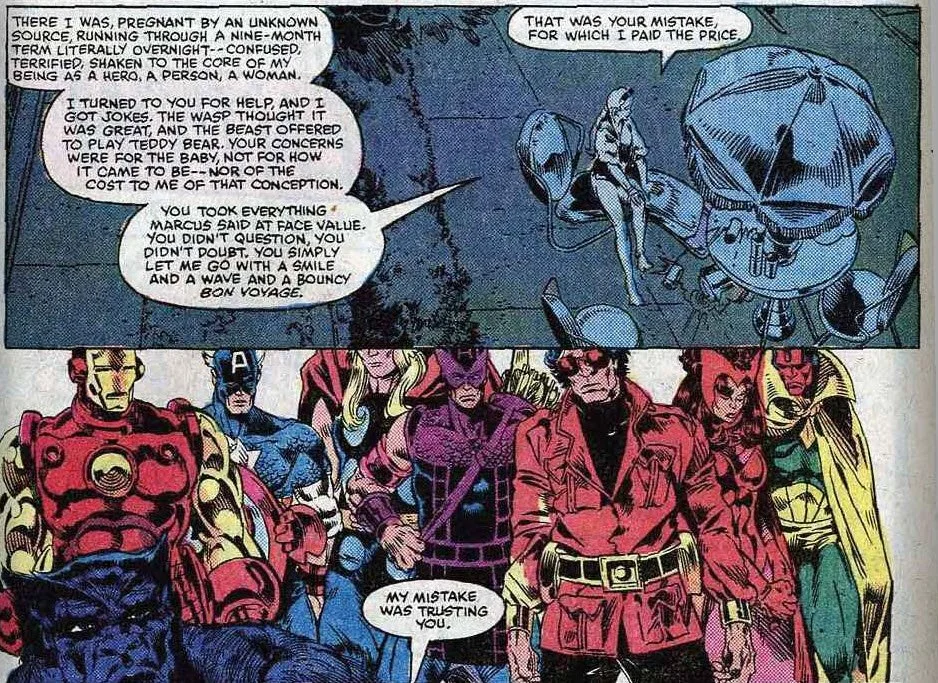

It would only be in Rogue's next appearance that we learn that the experience was traumatizing for her; Avengers Annual 10, quite understandably, focuses on Carol. In a book full of fight scenes (primarily with the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants), it is in Carol's confrontation with the Avengers in the last six pages that the real drama unfolds. Carol's weapon of choice is words (although she does actually slap Thor in the face at one point); the Avengers also speak, of course, but their words are, as in Avengers 200, cringeworthy misfires. Hawkeye the archer is particularly off the mark: "What happened to Marcus? After you left with him, we didn't expect to see you two lovebirds again." Carol explains what should have been obvious: Marcus (now dead) brainwashed her:

There I was, pregnant by an unknown source, running through a nine-month term literally overnight--confused, terrified, shaken to the core of my being as a hero, a person, a woman.

I turned to you for help, and I got jokes The Wasp thought it was great, and the Beast offered to play teddy bear. Your concerns were for the baby, not for how it came to be--nor of the cost to me of that conception.

You took everything Marcus said at face value. You didn't question, you didn't doubt, you simply let me go with a smile and a wave and a bouncy bon voyage.

At this point, her personality only recently reconstructed and her powers gone, all that is left of Carol Danvers is her trauma. Claremont immediately starts the long process of reconstructing her, bringing Carol into the X-Men's supporting cast for a year's time. She confronts the still-villainous Rogue again in The Uncanny X-Men 158 ("The Life that Late I Led...", by Claremont and Cockrum), and, on a mission to remove all record of the X-Men from government databases, erases her own double identity's personal files as well ("the women they represent...are strangers"), determined to "begin my life anew." Which she does, but, once again, through unspeakable suffering: when the X-men are captured by the alien Brood, her strange genetic make-up encourages them to experiment on her ("Though she is experiencing supposedly unendurable pain, she remains aware of all that transpires" (Uncanny X-Men 163, "Rescue Mission," by Claremont and Cockrum). After her rescue, she undergoes a transformation that gives her powers that are "the functional equivalent of a star" (Uncanny X-Men 164, "Binary Star," by Claremont and Cockrum).

At this point, Carol's days with the X-Men are numbered. Once back on Earth, with her ill-defined cosmic power set, the newly-Christened "Binary" could be just as difficult to fit into a team dynamic as Phoenix was, but with less reason for inclusion (Carol is not a mutant). Claremont has one last chance to explore Carol's trauma and recovery before handing her off to others; in Issue 171, "Rogue," with guest pencils by Walt Simonson, Carol visits her parents, frustrated that, while she has most of her memories, "there are no emotions to go along with them." She returns to the X-Mansion, only to find that the teams has inducted Rogue as their newest member. Naturally, a fight ensues, ending in an eerie parallel with Avengers Annual 10: Carol tells the team that she feels hurt and betrayed, and leaves.[1]

"Rogue" packs in more trauma per panel than any other X-Men story to date, featuring characters who are all trying and failing to recover. In the previous issue, Storm had just won leadership of the outcast mutants known as the Morlocks after stabbing the previous leader, Callisto, in a duel; now Callisto can barely stand. Scott Summer's new lover, Madelyne Prior, is having nightmares about the plane rash she survived, while Charles Xavier is unable to beat the phantom pain that prevents him from using his new, cloned body to its potential. Storm is so out of sorts that she can't water her plants without killing them, and ends the issue contemplating leaving the X-Men.[2]. But the main victim of trauma this issue, as well as its primary source, is the character who gives the story its title: Rogue.

Still suffering the aftereffects of her extended exposure to Ms. Marvel, she now has even less control over her powers than before (a problem exacerbated by Mastermind's unseen manipulation). Already obliged to cover her entire body lest she accidentally steal someone's memory or powers through casual contact, now she cannot distinguish between Carol's memories and her own. Most of the X-Men are unmoved by her plight, but Xavier insists that it is their responsibility to help any mutant who needs training. By the issue's end, Storm is considering quitting the team rather than tolerate Rogue's presence.

Rogue is quite likely Claremont's most successful rehabilitation of an antagonist; unlike Magneto, once she takes the X-Men's side, she never leaves. Claremont's real achievement, however, is making Rogue sympathetic, to the point of turning her into one of the most prominent X-Men characters throughout the entire transmedia franchise. She is a compelling combination of strength (nearly all of Ms. Marvel's powers, plus her own) and vulnerability (the aftermath of her absorption of Carol's personality along with the loneliness of her existence). She is a modern update of Cyclops, but one whose inner life amounts to more than just repression.

Notes

[1] Carol's ongoing recovery would become an important part of the next four decades (!) of storylines. After she loses her Binary powers and is reduced to her former Ms Marvel levels, Kurt Busiek has her rejoin the Avengers and quickly develop an alcohol problem. Once she gets her alcoholism under control, another unfortunate storyline forces her to confront an alternate version of Marcus, whom she forgives. Brian Reed's Ms. Marvel series sees her make her peace with Rogue, while most of the stories written about Carol as Captain Marvel emphasize her strength rather than her damage, even as she loses her memories (again), develops a brain tumor, and reevaluates everything she knows about her family.

[2] She is also only a few months away from an adventure in Japan that inspires her to adopt a leather-heavy punk look and ditch her knee-length hair for a mohawk.

Next: The Three Faces of Rogue

Revisiting the Rape of Ms. Marvel

By all rights, this comic should be a feminist horror film, a cross between The Handmaid's Tale and Get Out!

In Avengers 197, Ms. Marvel has a long talk with Wanda Maximoff about the Scarlet Witch's desire to have children. Scandalously, Carol reveals that she's not sure she ever wants to have any, whereupon she collapses in a sudden swoon. The issue ends with the revelation that she is three months pregnant--dramatic irony and sexist karma in a single package.

It turns out this is no ordinary pregnancy. The fetus is developing at an inhuman rate, and three issues later she is ready to give birth. The Avengers' big anniversary issue (200) is devoted entirely to Ms. Marvel's pregnancy, labor, and aftermath. Credited to a whopping four writers (James Shooter, George Perez, Bob Latyon, and David Micheline), "The Child Is Father to...?" has gone down in Marvel history as one of the most notoriously misogynist comics of the second half of the twentieth century (and one to which none of the four writers involved are so eager to proclaim paternity). The title of Carol A. Strickland's influential essay on the subject says it all: "The Rape of Ms. Marvel."

Carol gives birth quickly and painlessly in the beginning of Avengers 200, and despite the mysterious circumstances of her child's conception, not to mention his rapid growth to adulthood, all her teammates treat her condition as if it were a happy, welcome event (the Beast even shows up with a pile of sports equipment for her son). It is bad enough that the men cannot even begin to comprehend her feelings; even the two (childless) women on the team display a shocking lack of empathy:

The Wasp: "I just want to congratulate the proud parent. It's really a beautiful baby, Carol. You're so lucky to--

Carol: "Lucky?!" Wasp, think about what you just said!/ I've been used! This isn't my baby! I don't even know who the father is! / So if you want to help me, please.../ ...just leave me alone."

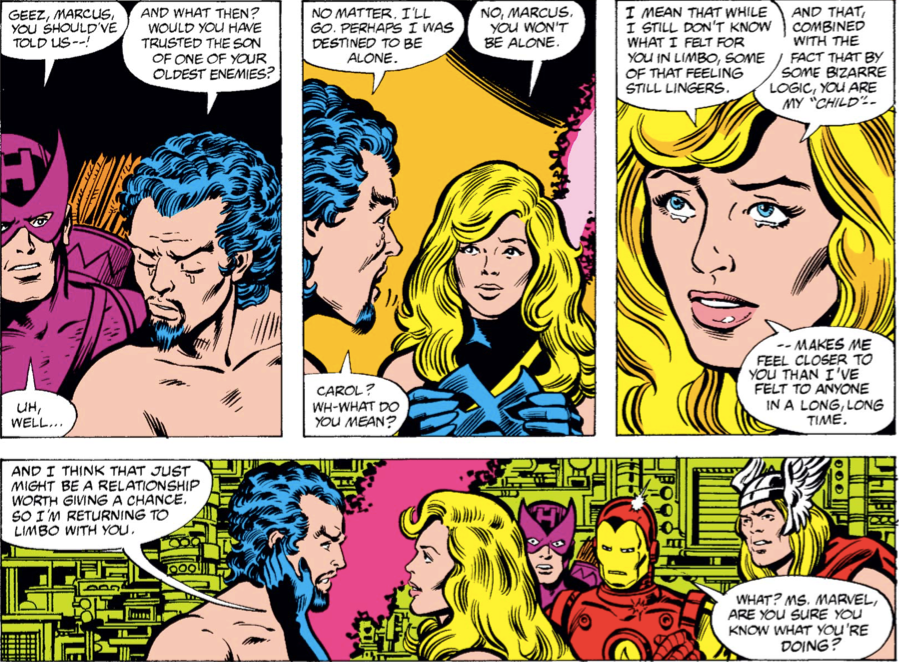

By all rights, this comic should be a feminist horror film, a cross between The Handmaid's Tale and Get Out!, but most of the issue paints Carol as the problem. The baby, now a grown man named Marcus, has been constructing a mysterious machine, and when Carol confronts him, he knocks her out ("Forgive me, mother. / Forgive me...my love.") After he is defeated, he finally reveals his origin. He is the son of the time-traveling lord of Limbo, Immortus. Immortus had gotten lonely, so he rescued the last survivor of a shipwreck, and courted her, supervillain style: "Once back in Limbo, through a combination of gratitude and the subtle manipulations of my father's ingenious machines," the woman fell in love with him. After giving birth to Marcus, the woman (who never even gets a name) disappears, and so does Immortus. A now-grown Marcus decides he needs to be born again on Earth, outside of Limbo, so that he can avoid the time distortion effect that took his mother. With all the consideration of a farmer selecting a cow for insemination, he "determined that Ms. Marvel, the powerful combination of Kree and human strengths, would be the perfect vessel." Like his father, he sets about "winning" the woman he kidnaps, wooing her for weeks "admittedly, with a subtle boost from Immortus' machines." Strangely, no one listening to his story seems to notice that he is describing brainwashing.

Marcus explains all of this to Carol and the Avengers, concluding, in his perfect proto-Incel fashion, "I'll go. Perhaps I was destined to be alone." But, inexplicably, Carol announces she is going with him:

I mean that while I still don't know what I felt for you in Limbo, some of that feeling still lingers.

And that, combined with the fact that by some bizarre logic, you are my "child"---

--makes me feel closer to you than I've felt to anyone in a long, long time.

And I think that just might be a relationship worth giving a chance. So I'm returning to Limbo with you.

This story so clearly misfires in its misogyny that most of its characters find themselves delivering thinly-veiled meta-commentary on how to receive it. Iron Man at least as the decency to ask if she's sure; Carol replies that she isn't, "but I've been denying my feelings for quite a while. Maybe it's time I started following them."

The last word is given to Carol's male teammates. Iron Man concludes that "we've just got to believe that everything worked out for the best." Hawkeye agrees: "Yeah, I guess you're right. That's all we can do. Believe.../...and hope that Ms. Marvel lives happily every after."

Avengers, or Abetters?

Iron Man and Hawkeye are half-heartedly trying to convince the readers that all's well that ends well, but the perfunctory manner in which Ms. Marvel is shunted off-stage to join her rapist is hard to miss. As a character, Ms. Marvel began as an attempt to capitalize on the interest in female superheroes, use the Marvel name, and, to quote Stan Lee, show "tits and ass." Claremont saved her from this fate early on, but with the book's cancellation, the Avengers writers never knew what to do with her. When characters stop appearing in comics for an extended period of time, fans and pros say that they are stuck in "limbo." This issue of the Avengers actually sends Carol off to a literal "Limbo," in the hopes that she can be comfortably forgotten.

Fortunately for fans (and for Marvel and Disney, which would go on to make a great deal of money on her cinematic counterpart), Carol did not stay in Limbo very long. Once again, Claremont came to her rescue, even if this formulation does frame Carol Danvers as a damsel in distress. Her salvation by Claremont gives her the tools to function as a viable character (eventually written by women), but her path to success is paved by further trauma.

Next: Going Rogue

Where Is My Mind? Rogue, Carol Danvers, and the Boundaries of Selfhood

The real throughline was Claremont's complicated, divided, traumatized women

After the Dark Phoenix storyline, The X-Men continued to tell powerful stories for the brief remainder of Byrne's tenure on the book, with the Days of Future Past two-part dystopian future storyline (141-142) and Kitty Pride's solo fight with a N'Garai demon (143) as particular high points. Over the next three years, Claremont worked with a variety of artists: Cockrum returned with issue 145, penciling sixteen out of twenty consecutive issues from 1981-1982, Brent Anderson drew two stand-alone stories and an annual (144, 160, and Annual 5), Bob McLeod did a two-parter (151-152), and Bill Sienkewicz drew two stories featuring Dracula (159 and Annual 6). Paul Smith was the regular penciler for roughly a year (165-170, 172-175), with a break for guest pencils by Walt Simonson (171). It was only in 1983 that Claremont would get a regular, long-term partner for Uncanny X-Men: John Romita, Jr., who, after an early stint on an annual (4), began a four-year run with issue 175 and ending with 211 (with other pencilers, notably Barry Windsor Smith doing the occasional issue along the way). [11] The first half of the 1980s saw the Uncanny X-Men lurch wildly from genre to genre, with long storylines briefly interrupted for unrelated adventures. The X-Men went into space, fought vampires, found themselves in alternate, mystical realities, and welcomed new members (though not always with open arms). To say that the one constant was change would not just be a cliché, but would also suggest a consistency of planning that was impossible at the time.

The real throughline for the the first half of the post-Byrne decade was Claremont's complicated, divided, traumatized women. Storm underwent a surprising character arc involving violence, love, and punk fashion. Colossus's sister Illyana was raised by demons in another dimension before returning home, having aged several years over the course of a few seconds. [1] The various iterations of Jean Grey are too complicated even to begin to describe yet. But the most intriguing exploration of duality, trauma, survival, and selfhood involved two characters very close to Claremont's heart. One of them was his (co-) creation, Rogue, and the other was a character he repeatedly rescued from weak writing and poor editorial policy, Carol Danvers (the current Captain Marvel). These women did not merely share a common trauma; in an event that will forever link them, each both causes and embodies trauma for the other.

Created by Roy Thomas and Gene Colan, Danvers was introduced in 1968 as part of the supporting cast for Marvel's first Captain Marvel, Mar-Vell (yes, there are far too many "Marvels" in this sentence, but hardcore comics fans will understand why this is unavoidable). [2] Originally the Security Chief at a military base, she overcomes her distrust to befriend Mar-Vell (an officer of the alien Kree). Exposure to an exploding Kree weapon gives her powers like his, and in 1977, she gets her own series as the heroine Ms. Marvel (created by Gerry Conway and John Buscema).[3] Ms. Marvel's initial adventures were, as we like to say nowadays, problematic: Carol had left the military to edit Womanmagazine for Spider-Man's nemesis J. Jonah Jameson, unaware that she had a second personality, a superpowered woman who wears a revealing version of Captain Marvel's costume, has no idea about Carol's existence, and has a precognitive "seventh sense" related to women's intuition.

“This female fights back!” Nothing says “empowerment” like taking a man’s costume and exposing the legs and midriff to make a female version.

Claremont took over the title with issue 5, joining penciler Jim Mooney, who was already on the book. By this point (1977), Claremont had already shown his facility for writing "strong female characters"; this phrase is generally inadequate due to its emphasis on strength over complexity, but not out of place when applied to Claremont's women, who exemplify both qualities. Claremont quickly dispensed with Carol's dissociative identity disorder, downplaying the aspects of the book that were based on stereotypical feminine weakness. He gave her a more developed backstory, including both a reasonable adult history of past romantic relationships and a long record of professional accomplishments. But with the benefit of hindsight, Ms. Marvel's introduction as the alternate personality of an unknowing Carol Danvers inadvertently established a pattern for all the iterations of the character to follow: Carol's sense of selfhood is repeatedly under threat.

With Claremont, though, Carol Danvers was in safe hands. Unfortunately for her, she was also a semi-regular character in the Avengers, where her strident "women's lib" received the occasional pushback.

And then things got really bad.

Notes

[1] Both Storm and Illyana have fascinating character arcs during this period, but they are not covered here out of concerns for space.

[2] A very quick summary of a very long story: created by C.C. Beck, the original Captain Marvel was published by Fawcett Comics. National (DC) sued Fawcett for copyright infringement over his similarities to Superman. The end result was Fawcett's closure and DC's acquisition of Captain Marvel and his supporting cast. Meanwhile, Marvel decided that if anyone should publish the adventures of a character named "Captain Marvel," it should be them. This is why the DC adventures of the original Captain Marvel are usually given the title "Shazam."

[3] This origin is later retconned to make Carol less dependent on Mar-Vell, but that is not relevant to the present discussion.

Next: Revisiting the Rape of Ms. Marvel

Jean Grey, Bad Girl

The men in Jean's life cannot help her without depriving her of agency

The Dark Phoenix trilogy (X-Men 135-137) is one of those landmark stories that, thanks as much to its influence as to changes in storytelling styles, can read like a collection of clichés. In the four decades since, heroes have gone "dark" again and again, especially female heroes, and the tropes involved have moved from comics to animation to television and film. The Phoenix saga has been revisited on multiple occasions in the various volumes of What If?, retold in Marvel's Ultimate Comics line, adapted for the 1990s animated series (with a happier ending), served as the basis of two different X-Men movies (X-Men: The Last Stand and X-Men: Dark Phoenix), and used as the obvious model for Willow's corruption on Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. Sue Richards went briefly dark to become "Malice" when John Byrne was writing and drawing Fantastic Four, while Wanda Maximoff's descent into madness and occasional evil was a years-long set of Avengers plotlines that inspired WandaVision and Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness. Starting in the 1980s, comics creators realized that Lee and Kirby's aversion to giving female characters physical powers meant that their potential was actually far greater than that of their male counterparts (Jean, Sue, and Wanda being the salient examples). The contrast between their 60s and modern power sets lent itself to drama, but the frequency with which specifically female characters found themselves overwhelmed by near godlike-power looks suspicious. These women's journeys complete a full circle from helplessness to strength back to helplessness again.

The Dark Phoenix storyline thoroughly committed to the metaphor of the divided self, to the extent that it was never clear whether or not the Phoenix was actually a separate entity. Both the captions and Jean's own dialogue suggested that the Phoenix was a primal force (and therefore existed before the space shuttle incident), while Claremont's tendency to have characters refer to themselves in the third person for dramatic effect did not help matters ("Dark Phoenix knows nothing of love!" X-Men 136). Not long before her suicide, Jean explains to Colossus:

Two beings--Jean and Phoenix--separate--unique--bound together. A symbiote, Peter; neither can exist without the other.

Phoenix provides my life force, while I provide a living focus for its infinite power.

[..]

The Phoenix is a cosmic power. It can neither be contained nor controlled---especially by a human vessel. Return it to the cosmos which is its home.

Kill me! ( X-Men 137)

Jean Grey’s secondary mutation: drama queen

Within the fictional framework of the X-Men, Jean's explanation can be taken at face value. Indeed, it serves as the basis for a massive retcon years later, allowing Jean to come back to life, unburdened by responsibility for the Phoenix's actions. [1] But it also literalizes the metaphor of divided self to the point of dissociation. Hence Jean's ability to watch the Phoenix's actions at a distance: it is her, but it is also not her.

In any case, the retcon about the Phoenix Force is not relevant here, if we want to read the comic as it could have been read when it was first published (September 1980); Jean would remain dead for over five years before she was brought back in Fantastic Four 286 (January 1986). Moreover, to the extent that one cares about authorial intent, once Jim Shooter forced Claremont and Byrne to redo the last pages of X-Men 137 to kill Jean rather than simply de-power her, both of them wanted her death to stick. [2] Without the "Phoenix Force," Jean's dichotomy is much more interesting.

When Scott confronts Jean at the end of X-Men 136, he addresses her as Phoenix, before telling her, "You're also still Jean Grey, no matter how hard you try, you can't exorcise that part of yourself. It's too fundamental." This is when she replies to him in the third person: "Dark Phoenix knows nothing of love." Scott disagrees; everything that led her to become Phoenix was motivated by love: "Jean, you are love!" Her response is revealing: "I...hunger, Scott---for a joy, a rapture, beyond all comprehension. That need is a part of me, too. / It consumes me." The Phoenix is a creature of passion, but the thing she and Jean share (as one entity, speaking in the first person) is appetite. As so often is the case in superhero comics, the metaphor is literalized: in the previous issue, Jean/Phoenix, in a thought-ballooned monologue whose tone is completely consistent with Jean's speech patterns before and after becoming Dark Phoenix, has to admit that "like it or not--and I don't--I still have limits./ I'm ravenous. Before I go on, I need sustenance./ This star should do nicely." She consumes that star, killing the five billion people in its orbit. Jean Grey, who has spent her entire adult life in love with Scott Summers, the past master of self-denial, is undone by needs that she cannot suppress.

Yeah, Scott’s not going to fill that hunger

Defeating Dark Phoenix, even temporarily, requires curbing her power, her needs, and her passion, all at once. The middle part of the trilogy shows three different men attacking the "problem" from different angles. Hanк McCoy (the Beast) has thrown together a "mnemonic scrambler" that will interfere with Jean's psychic. powers: "she shouldn't be able to think a coherent thought, much less read minds or throw telekinetic bolts," he tells Scott. It as it this moment that Claremont engages in what seems to be a typically superfluous elaboration of a character's power set. As he takes off his visor and puts on his glasses, he thinks:

I can't open my eyes, even the tiniest fraction, until I've put on my special ruby quartz glasses, or my optic blasts could punch a truck-sized hold in the wall.

I've had to be this careful since before I joined the X-Men. I'll have to stay this careful till the day I die.

Ok, Scott, we get it, but is this really the time for your whining?

The adherence to the premise that "every comic is someone's first comic" here is almost endearing; X-Men 136 is not just the middle installment of a trilogy, but the eighth issue of a nine-issue trilogy of trilogies, not to mention the culmination of years of subplots. But this exposition is, in fact, going somewhere. Scott continues:

Ororo wants to help me, to comfort me. But I can't given in. Not yet. If I give full rein to my feelings, i'll....shatter.

For Jean's sake, as much as everyone else's I have to stay strong... in control.

Dude, I don't know how to tell you, but that’s not Ororo

In other words, Scott is facing Jean's dilemma on a much smaller scale, but it is one he has grappled with for his entire adult life. Beast's attempt to defeat Dark Phoenix with technology only works temporarily, letting Jean's human side emerge and beg Wolverine to kill her, but this, in turn, only plays on Logan's emotions and prevents him from taking action. When Jean burns out the mnemonic scrambler, Cyclops takes his turn. For once, though, instead of serving as the voice of repression, he approaches Phoenix on her own turf: passion and love. Once again, the connection between Phoenix and her attacker/interlocutor is cut short, but not by Phoenix; Xavier strikes her down with a mind blast. As the final issue of the trilogy will show, bypassing Phoenix and breaking through to Jean is always a temporary measure: they are linked by passion, and appeals to Jean emotions are a gateway right back to Phoenix. Xavier is the only one who can fight her on her own terms, and not just because of the nature of their abilities. He tells Phoenix that she represents "Power without restraint--knowledge without wisdom--age without maturity--passion without love." Implicitly, Xavier embodies all that she lacks. Yet this, too, will be a temporary solution: the Phoenix will always come back.

And this is part of why the end of the Dark Phoenix trilogy works so well, despite being imposed on the creative team at the last minute by an uncompromising editor-in-chief. The men in Jean's life, even with the best of intentions, cannot help her without depriving her of agency. In that regard, the original ending, with Empress Lilandra performing a "psychic lobotomy" to remove Jean's power is, while not as egregiously gendered, even worse. The only way for Jean to remain true to one version of herself is to kill both.

But even as the Dark Phoenix Saga paves the way for Claremont's many other divided and tortured female characters, Jean's suicide forecloses what would become the most productive avenue for Claremont's exploration of his characters's conflicted psyches: she does not survive the experience long enough to even begin processing her trauma.

Or at least, not yet. After her revival in the mid-1980s, Jean's internal divisions become externalized. Rather than having too many selves in one body, there will be too many iterations of Jean Grey for her to maintain a stable identity. Her dilemma is shared by Claremont himself, who was obliged to make sense out of Jean's resurrection after already populating the X-Men's world with a lookalike (Madelyne Pryor) and Jean's daughter from an alternate future (Rachel Summers, who eventually takes the name Rachel Grey). Claremont generally prefers his characters to contain multitudes, rather than to have multitudes consisting of variations on the same character. We will see how he manages, but only after examining the divided selves he explores in the interim.

Notes

[1]. Fantastic Four 286, written and penciled by John Byrne, and based on an idea by Kurt Busiek, reveals that Jean was never actually the Phoenix. On the verge of death while piloting the space shuttle, she is visited by the "Phoenix Force," which makes a deal with her: Jean will serve as the template allowing Phoenix to exist on our plane, and the Phoenix will save her life. Jean's body is slowly healing in a cocoon at the bottom of Jamaica Bay, while the Phoenix takes her place, believe itself to actually be Jean Grey.

[12] Byrne even showed up at Chicago ComiCon in 1980 wearing a custom-made t-shirt saying "SHE'S DEAD AND SHE'S GOING TO STAY DEAD" (https://www.fandom.com/articles/jean-grey-changed-death-comics)

Next: Where Is My Mind? Rogue, Carol Danvers, and the Boundaries of Selfhood

Evil Mutant Bondage Goddess

The Black Queen embodies Jean's dark, passionate side as pure transgressive sexuality (her black leather corset, boots, and whip are among the many cues that are hard to miss)

The Scott/Jean/Logan triangle would become a recurring motif for years, apparently resolved by the strong implication that, on Jonathan Hickman's utopian Krakoa, they had become a throuple. But it is a triangle that barely existed during the Claremont/Byrne run. Instead, Cyclops's competition is Jason Wyndgarde. Wyndgarde (the previously-undisclosed real name of the long-time X-Men illusion-casting villain Mastermind) has been stalking Jean ever since Scott and most of the X-Men were thought dead at the end of X-Men 113. Whenever they bump into each other, Jean suddenly finds herself dressed in late-18th century garb, in a relationship with Jason. She assumes these are Phoenix-inspired "timeslips" to the life of an unknown ancestress, rather than illusions, and with each encounter, she sinks deeper into this fantasy scenario. Manipulated by Mastermind, Jean discovers depths of passion she had not known, along with a previously undiscovered streak of cruelty; in one scene, she and Jason are on horseback for a hunt. Jason hands her the knife to "administer the coup de grace," while complementing her on the clever twist she brought to the sport:

"It was a masterstroke of yours....

"suggesting we hunt a man, playing the role of stag, rather than the animal itself."

Saved by a well-placed panel border

Where Wolverine wants to release Jean from her inhibitions so that she can follow her passionate nature, Wyndgarde is using sex and violence to seduce Jean into pure evil. And not just any evil: he is molding her into his "Black Queen" (in the Hellfire Club, which Wyndgarde is working for, the leaders are all Black or White Kings and Queens). The Black Queen embodies Jean's dark, passionate side as pure transgressive sexuality (her black leather corset, boots, and whip are among the many cues that are hard to miss). Again, the "timeslip" scenario, like the Dark Phoenix story that follows it, allows Jean both to experience her actions and watch them from a remove, with the moral distance from what seems like a dream.

Approved by the Comics Code!

Even though the Scott-Jean-Logan triangle was barely developed at the time, it still thematically reinforces Jean's path towards darkness. From the time Jean assumes the Black Queen persona (Uncanny X-Men 132) through the first appearance of Dark Phoenix (the last page of Uncanny X-Men 134), Scott's main role is to be a punching bag, while Wolverine cuts loose as never before. The first thing Jean does as the Black Queen is knock him out with a powerful telekinetic blast ("Had the Black Queen struck to kill, there would be nothing of the lad but ashes."). The same issue ends with one of the most iconic panels in the history of the X-Men. Wolverine rises out of the sewer, releases the claws on his right arm, and turns toward the reader: "Okay, suckers--you've taken yer best shot! Now it's my turn!" Wolverine will spend the next issue cutting his way through the bad guys more savagely than he ever had to date, while Cyclops, realizing his primary metaphor, is restrained and blind, with his face covered to keep his eye beams in check. As Wolverine continues to hack up his enemies, he pauses so as not to kill adversaries who might be "legit club employees," while Scott faces Wyndgarde in the psychic plane, only to be run through by Mastermind's sword. Scott succeeds in shocking Jean out of Mastermind's control, but only by "dying," while Wolverine deals death left and right. Scott's success, however, only advances Jean down the road to Dark Phoenix. In other words, letting Jean embrace the side of herself that is much more like Wolverine.

Yeah, but you’re still covered in sewer sludge

The entire fight with the Hellfire Club, that is, the sequence that leads to the rise of Dark Phoenix, is an indirect comment on the dilemma of passion and restraint that Jean cannot initially resolve. True to his supervillian name, Wyndgarde has masterminded the whole process through a scenario that only involves the simulation of action: using illusions to convince Jean that she is already about to commit violence and embrace evil. The leader of the Hellfire Club, Sebastian Shaw, turns out to have a power that is initially unstoppable, as he absorbs the kinetic energy of any physical attack against him, thereby growing in strength. Only during their rematch to the X-Men realize that he can only be defeated by attacks that avoid physical confrontation (Storm uses her powers to slowly freeze him). Shaw's comrade Harry Leland has the power to increase the mass of other objects, but his use of it on Wolverine as the X-Man leaps towards him only means that he is hit with even greater force. The X-Men win through the careful deployment of restraint, but it is too late for Jean: she has cast off all moral qualms and become Dark Phoenix.

Next: Jean Grey, Bad Girl

What Does Superwoman Want?

If Phoenix is a metaphor for women who embrace their sexuality, Cyclops is the adolescent male who is afraid of his own desire and its capacity to cause harm

Four decades later, it is clear that Phoenix is the first in a long list of female characters whose godlike superpowers must be tempered, removed, or contained, and whose inability to cope starts to look as much like a reflection on their gender as on their individual character. But at the time, Phoenix's dilemma was novel, as was her descent into the dark side. This does not shield Claremont's, Byrne's, and Cockrum's decisions about her character from a critique on the ground of gender, but it does mean that, when Jean Grey constituted a sample size of one, there was space to consider her character development as something more than a sexist trope that hadn't even been fully established yet. As we shall see, Claremont's own preoccupation with powerful, but traumatized women retroactively makes Phoenix one of many female characters treated in this manner, but for the moment (and only for the moment) I propose giving Claremont and company the benefit of the doubt. They were among the first to give a Marvel superheroine real power and personality, and seemed to have been attracted to the greater emotional range imputed to women than men in a heteronormative framework. The very things that made Jean and characters like her feel more real were their contradictions, weaknesses, and flaws. Gender cannot be removed from this equation (look no further than how these women are drawn), but it is not the only factor.

In Marvel Comics in the 1970s, I argued that the best writers of Marvel's second decade took the limitations of the form and the medium as a challenge to represent the inner lives of characters who were available to their readers primarily through visual representation. Many of them moved away from Lee's predilection for monologues to voiceover narration (via captions) and introspection (via thought balloons), in order to demonstrate the relative complexity of the characters whose adventures they chronicled. They also tended to complicate the metaphor implicit in the secret identity: rather than simply contrast the civilian identity and the alter ego (most dramatically in the cases of Thor and the Hulk, who became different people in order to wield their powers), they gave the reader access to the inner workings of characters whose complexity could not be encapsulated by simple binary oppositions (quite literally in the case of Deathlok, whose narration initially included the three different voices arguing in his head).

Claremont did something different from Gerber, McGregor, and company: he doubled down on Stan Lee's declarative mode. The monologues moved from word balloons to thought balloons (and back), but his characters still expressed themselves in soliloquies. The result felt like a continuation of his colleagues' preoccupation with inner states of mind, but with an almost complete lack of subtlety and a greater interest in melodrama (of both inter- and intra-personal kinds). He revived Lee's binarism, but turned it into something resembling introspection: Claremont's characters, rather than being split between one identity and another, were constantly balancing the opposing impulses that made them who they were. It was almost as though the heroes had a devil on one shoulder and an angel on the other, except that the devil and angel were the two halves of the characters themselves.

In the case of Jean Grey, this meant that the power of the Phoenix constantly tempted her to throw off the WASPy repression of her Lee/Kirby/Thomas/Adams years and give herself over to her emotions. The Phoenix, we are told, is a creature of passion, and Jean is always aware of the surprising satisfaction that comes from letting her powers (and passion) loose. One of the strengths of Claremont's writing is how he takes advantage of the inherent contrast between words and pictures: while Phoenix is blasting Firelord with all her might, she is also watching herself from a distance, noting her own reactions. Inner Jean both experiences her feelings and records them like an unsettled observer who is too fascinated to look away.

Where the story becomes undeniably gendered is its representation of Jean's two sides through romance, particularly through the men she finds attractive. On one side is Scott Summers, the X-Man whose superpower may as well be repression. If Phoenix is a metaphor for women who embrace their sexuality, Cyclops is the adolescent male who is afraid of his own desire and its capacity to cause harm. As often happens in superhero comics, the metaphor is quite clear (only Edward Scissorhands is more obvious about it): Scott's optic blasts are so powerful that if he opens his eyes without the benefit of his visor or protective glasses, he could kill anyone he looks at. In X-Men 94, when he considers leaving the team along with all the rest of the original X-Men, he stands at a window, delivering an impassioned soliloquy about his inability to live a normal life because of his "cursed, mutant energy-blasting eyes." The Hulk and the Thing can also function as a stand-in for the adolescent boy who doesn't know his own strength, but Cyclops's case is more clearly interpersonal and sexual: he cannot look anyone in the eye, and the projectile force he emits from his body is potentially lethal. This is why the scene in X-Men 132, when Jean removes his visor and uses her powers to block his optic blasts, is such a powerful rendering of Scott's vulnerability and Jean's strength: finally, he does not have to be afraid of hurting her. And it is strongly implied that at last they have sex for the first time.

This one’s a keeper, Scott! I hope she doesn’t, I dunno, go crazy, eat a star, and kill herself on the moon

In contrast to Scott, we have two different men. Decades of lore and some intense retconning by Claremont would have one of them be Wolverine. When Jean is in the hospital after becoming Phoenix, Logan buys her flowers and hopes to reveal his feelings for her, before seeing that the rest of the X-Men have beat him to the waiting room (X-Men 101). By the time Jean becomes Dark Phoenix, the readers know Wolverine is in love with her. But it is only later, after she has died for the second time, that Claremont goes back and adds Jean's side of their relationship in the brief stories included in the Classic X-Men series. There we find out that Jean's decision to leave with the original team was because of Logan. While Scott was monologuing by his window, Wolverine was hitting on Jean, and Jean found herself responding.

Next: Evil Mutant Bondage Goddess

Flight of the Bird Metaphor

Jean Grey’s transformation is the embodiment of Claremont’s unspoken mission statement: to create a comic about powerful women

Claremont was a master of the team book, developing back stories and inner lives for nearly all his characters. But with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that, even as he deftly balances the X-Men ensemble, there is usually one character or relationship around whom most of the action and angst revolves, even threatening to dominate the entire book. By the time the series was reaching its 100 mark, all the way through the Dark Phoenix Saga, the center of gravity was Jean Grey (and, to a lesser extent, her relationship with Scott Summers). This was not a foregone conclusion; one could easily imagine a new writer on a revitalized franchise gravitating towards the characters with the least amount of backstory and, therefore, the most room for development. Instead, Claremont and his collaborators used this longstanding, but rather undeveloped, relationship as the anchor for the series.

Claremont's transformation of Jean Grey now looks like the embodiment of his unspoken mission statement: to create a comic about powerful women. When Jean Grey was introduced as Marvel Girl, the newest member of the team in X-Men 1, she was yet another example of Stan Lee's nearly interchangeable heroines. The early Marvel women tended to have non-physical powers that nonetheless put a strain on their delicate constitutions; Marvel Girl, the Invisible Girl, and the Scarlet Witch typically used their minds to intervene in battle, and then swooned from the effort. In their interactions with their team mates, they asked the questions that gave the men chance to explain things, exclaimed their shock and horror, and revealed their unspoken passions in thought-balloon encased monologues. Every now and then, they expressed dissatisfaction with being coddled or sidelined, but their complaints were usually presented as amusing petulance. The best that could be said about them was that their presence at least meant that the teams weren't made up entirely of men.

Claremont and Cockrum brought Jean back in Issues 97 and 98, only to have her (along with Wolverine and Banshee) captured by the Sentinels and transported to a space station. The other X-Men come to the rescue, but the ensuing battle destroys the station. Barely escaping on a cramped shuttle, they have to make their way back to Earth through a solar flare. Part of the craft is shielded, but not the cockpit. Jean decides that her telepathy and telekinesis make her the only one who has a hope of surviving long enough to pilot the shuttle back to earth. A cliffhanger at the end of issue 100 sees her overwhelmed by radiation; in the next issue, the X-Men crash land in Jamaica Bay. Jean, who had been presumed dead, suddenly shoots up from the depths of the bay wearing a new costume, proclaiming the now-famous words: "Hear me, X-Men! No longer am I the women you knew! I am fire and life incarnate! now and forever, I am PHOENIX!"

In real life, a man would immediately start imploring her to “calm down”

It would take months for the ramifications of Jean's new identity to begin to play out, since she spends a fair amount of time after Jamaica Bay in a coma. But when Claremont and Cockrum are finally ready for Phoenix's real debut, they immediately make it apparent that she is now operating on another level entirely: the first antagonist she faces is Firelord, a former herald of the world-eating Galactus. If it were not already clear enough that Jean is now a cosmic-level hero, she interrupts the fight to use to open a stargate to the far-off Shi'ar Empire with her power, learns that a crack in an ancient MacGuffin called the M'Kraan Crystal is about to destroy all reality, uses the strength of the Phoenix to bind her teammates' vital energies together into a gestalt organized along the principle of the Kabbalah's Tree of Life, and saves the universe.

After this story, her power levels would fluctuate, largely because Claremont and Byrne disagreed over the wisdom of including an omnipotent X-Man (Claremont was for it, Byrne against). The course of the Phoenix Saga translated Byrne's and Claremont's arguments over Jean's powers into a crucial aspect of both the plot and her character development. If Byrne's point was that a character so powerful made her team members extraneous (that is, undercut the very nature of a superhero team book), the story represented her near omnipotence as a threat to Jean's own selfhood (not to mention the continued existence of the universe). The result was a fascinating combination of the cosmic and the personal accomplished while also permanently grafting space opera and metaphysical drama onto the X-Men formula.

Jean's time as the Phoenix is the story of two simultaneous seductions, one by the power itself, and one by bad actors taking advantage of her situation: Jason Wyndgarde, better known as Mastermind, using his illusion-casting powers with the help of the telepathic White Queen to make Jean think she is mentally traveling back to the lives of previously unknown ancestors. At roughly the same time that the first Star Wars trilogy was developing a none-too-subtle drama involving the lure of the "dark side" of the Force, Jean was confronting her inner demons with the assistance of a few of their outer counterparts. While both Star Wars and the X-Men are thoroughly melodramatic, there are two key differences: first, that Claremont is much better at getting into his characters' heads than George Lucas, and second, that the Phoenix is female.

Next: What Does Superwoman Want?

New Recipe X-Men

Claremont & Byrne's X-Men run was the 1970s comic that created 1980s Marvel

Claremont also quick to develop the X-Men’s distinct personalities (well, for most of them: Thunderbird was killed off almost immediately, while it took years for Colossus to be anything more than a simple Russian collective farm boy with a propensity for spouting non-existent Russian oaths). Though Storm lived as a "goddess" in Kenya when Professor Xavier found her, she was actually the Chicago-born daughter of an American journalist and an African mother; when she was a child in Cairo, her parents were killed during an air raid, and her time trapped in the rubble left her with debilitating claustrophobia. [1] Nightcrawler offset his anxieties about his monstrous appearance with an easy sense of humor and a swashbuckling air. And the book's breakout character, Wolverine, combined a propensity for savagery with nobler impulses, while coping on his own with a confusing and traumatic past.

Remembering the 1970s X-Men is complicated by a strange set of circumstances. The comic entered the 1980s on the verge of becoming the company's biggest franchise, on the strength of the Claremont/Byrne run that began earlier and ended before 1980 was out. Claremont & Byrne's stories are widely regarded as foundational, the X-Men's golden age, and yet the franchise's commercial success came later; when Byrne started on X-Men, the book was still bimonthly (a sign of precarity). Their biggest storyline, the Dark Phoenix saga, was the culmination of years -long plotlines in the 1970s, though most of it came out in 1980s. Perhaps the best way to look at would be to say that Claremont & Byrne's X-Men run was the 1970s comic that created 1980s Marvel.

In the lead-up to the Dark Phoenix Saga all the way through the first two years of the 1980s, Claremont (first with Cockrum, then with Byrne, then Cockrum again) established lore that would become fundamental to the X-Men going forward:

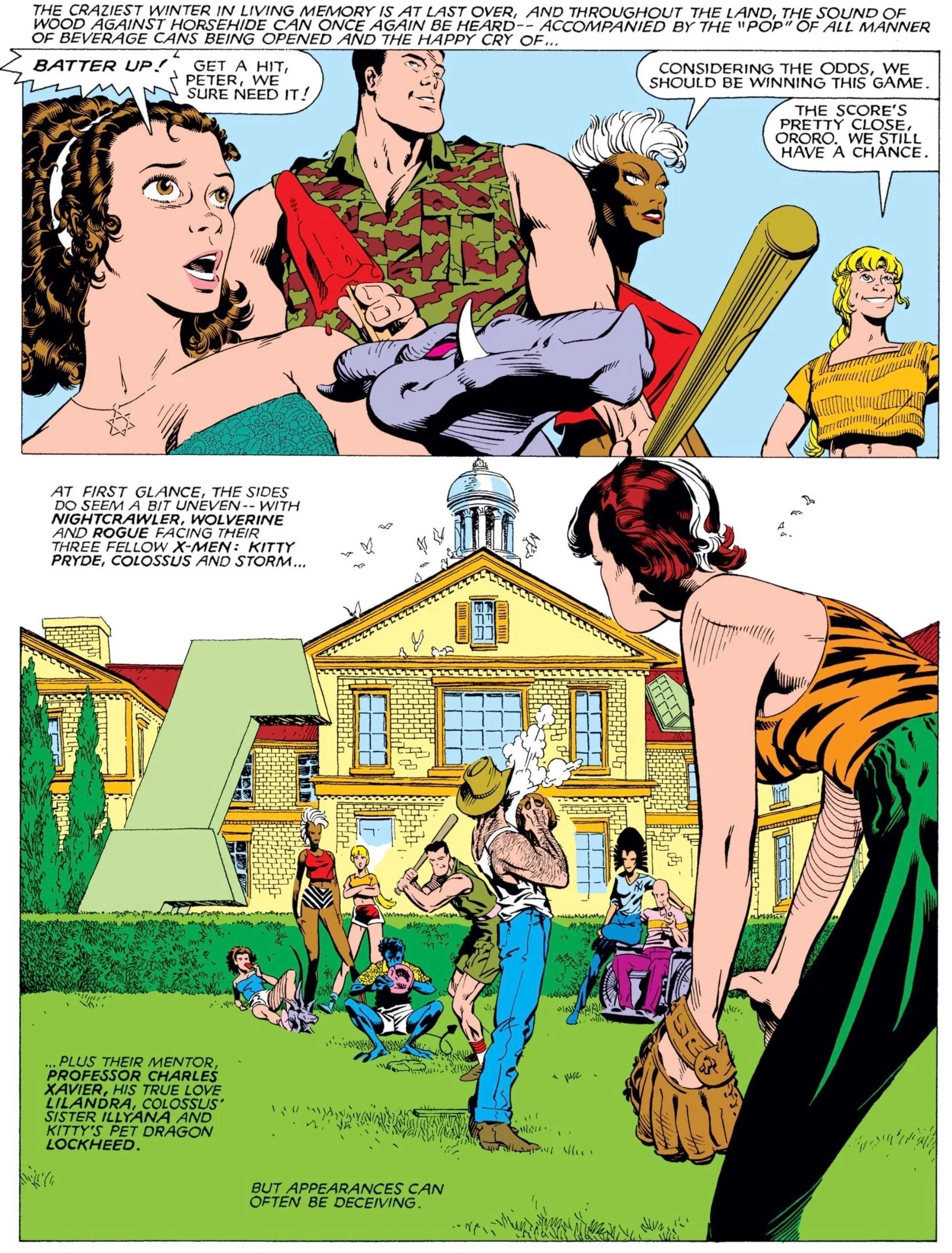

Would mutants be less hated and feared if they played more baseball?

The divided self. Claremont's characters are constantly torn between two poles, hence the common refrain "Part of me wants... but part of me also..."

Mutant hatred as a long-term, constituent element of the X-Men's world, from local hate groups to secret societies to the top reaches of government

Seduction to the dark side

Tortured romance

A strong focus on female characters, and (eventually) their friendships

Trauma

Revelations of characters' secret backstories (Magneto, Moira MacTaggert)

The humanization and even rehabilitation of villains (tentatively begun with Magneto in X-Men 125, but becoming much more common in the 1980s)

Japan as a frequent location and set of tropes

Professor X's departures and returns

Space Opera (a favorite of Cockrum's). The introduction of the Shi'ar Empire (whose empress falls in love with Charles Xavier) and the Starjammers (whose leader turns out to be Cyclops' father)

Moral dilemmas about killing

Long-running subplots that could take years to pay off (if they ever do)

Alternate futures

Death and resurrection

Islands [2]

Magic (not a strong part of the Byrne and early Cockrum runs, but picking up immediately after)

Mind control that leads to the adoption of outfits resembling fetish gear

Baseball. Lots and lots of baseball. [3]

This is not even counting the many set phrases that Claremont uses throughout his run on the X-Men, to the point of near self-parody. [4]

Notes

[1] As if this backstory were not complicated enough, Claremont would eventually reveal not only that Ororo had a latent talent for magic because of a hitherto-undisclosed sorcerous heritage, but that, in her teenage years, she had a budding romance with T'Challa, the future Black Panther.

[2] The revived X-Men's first adventure involves the living, mutant island of Krakoa. Issue 104 reveals that Moira MacTaggert, introduced as the X-Men's new housekeeper, is actually a Nobel-prize winning biochemist with a Scottish research facility on Muir Island. The storyline culminating with Issue 150's "I, Magneto," takes place on a mysterious island that will briefly serve as the X-Men's home (as well as the gateway to Limbo). Over the years that follow, Krakoa is brought back in various forms, Wolverine spends a great deal of time on the corrupt island city-state of Madripoor, the X-Men have numerous adventures involving the island city-state Genosha, which starts out as a country that enslaves mutants, is taken over by Magneto as a new mutant homeland, only to be the subject of the single largest genocide in Marvel Earth's history when Cassandra Nova wipes out the entire population. Later Cyclops establishes a mutant island utopia with the unimaginative name "Utopia." When Jonathan Hickman revitalizes the franchise in House of X/Power of X, he engages in a creative distillation of key X-Men tropes, not just resurrection from death and mutant separatism, but also the centrality of the island utopia (Krakoa once again).

[3] The X-Men first play baseball in issue 110, guest penciled by Ton Dezuniga. Eventually it would become a frequent X-Men pastime.

[4] "I'm the best there is at what I do, but what I do isn't very nice." "Part of me... but part of me..." "And I, you, with all my heart." "For all my vaunted power..." "I possess you, body and soul!" "No quarter asked, none given." "I...hurt"

Next: Flight of the Bird Metaphor

All-New, All-Different

The X-Men offered avenues of identification for readers who might not even know that they needed it

When Lee and Kirby's X-Men first appeared in 1963, it was one of many creations that were released in the wake of the book that launched modern Marvel, the Fantastic Four. Some would become great hits (Spider-Man, Thor), others would forever remain second -stringers (Ant-Man, The Wasp), and a third category would need a fair amount of time to really take off and sustain their own books (The Hulk, Iron Man).[1] X-Men sustained a nearly seven-year-long run of original material before becoming a reprint series at the end of 1970, with occasional guest appearances by the characters in other books over the next five years.

X-Men was a team book unlike the company's better-selling Avengers or Fantastic Four. The Avengers, like DC's Justice League, were a combination of heroes who had their own titles (Thor, Iron Man, eventually Captain America) and characters who were building a fanbase as team players (over time, Hawkeye, Quicksilver, the Scarlet Witch, and the Vision). The Fantastic Four was a family. But the X-Men had more in common with the groups of characters favored by Jack Kirby: the hidden civilization of the Inhumans, the far-off, self-contained adventures of the gods of Asgard, and, in the 1970s, the mysterious, isolated Eternals (who were never even meant to be part of Marvel's main continuity, let alone ruin the track record of the Marvel Cinematic Universe). Though the X-Men's power sets could easily have been the results of the ubiquitous radioactive accidents that created the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, and Spider-Man, instead the characters were mutants: born different from the rest of humanity, and therefore marked as outcasts. It would take years for the public's love of the Avengers and their irrational fear and hatred of mutants to become a story point, but that did not matter on the pages of the X-Men comics themselves. The purpose of a comic about mutants rather than generic superhumans was to explore alienation, racial hatred, and the possibility of reconciliation.

Where DC's heroes, and even many of Marvel's, were aspirational, the X-Men's appeal stemmed from their status as outcasts. In the tradition of twentieth-century science fiction and fantasy written primarily by straight white men, mutants became an all-purpose metaphor for any kind of difference, facilitated by the fact that almost all the initial mutants were straight white men. [2] Mutants allowed for the exploration of alterity without the baggage of actually existing alterity. The mutants could stand for Jews without being coded as Jewish, for African Americans without being Black, and, eventually, for queer people without explicit depiction of queerness. Sixty years later, the limitations of this approach are glaring, but this does not take away from its power at a time when real explorations of difference, particularly in a medium intended for children, were few and far between. The X-Men offered avenues of identification for readers who might not even know that they needed it.

X-Men did not keep its original creative team for long; Kirby was frequently joined by a co-penciler, and he and Lee both left after issue 19. During their tenure, they introduced several important features of X-Men lore: Magneto, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, Professor Xavier's evil half-brother the Juggernaut, and the Sentinels. Though the Sentinels would not become frequent antagonists until years later, these mutant-hunting robots signified that more was at stake than in an ordinary superhero story. Mutants were being threatened with genocide. [3] Lee and Kirby were succeeded by Roy Thomas as writer and Werner Roth (and then Don Heck) on pencils. Other teams followed, but the comic only started to stand out again when it was reinvigorated by younger artists (Jim Steranko, Barry Smith, and Neil Adams). Thomas and Adams' run on the comic remains beloved, but cancellation (in the form of the shift to an all-reprint format) put this brief experiment to an end.

Yet the X-Men still had their fans, including in the Marvel Bullpen itself. During the Seventies, both Marvel and DC were willing to take chances on a wide variety of new books and new approaches, which led to Len Wein and Dave Cockrum creating a new team of X-Men in Giant-Size X-Men 1 ("Deadly Genesis!" May 1975). The next issue of the regular book (94) dispensed with the reprints (in mid-storyline, much to the frustration of my eight-year-old self) and continued the story of these new characters. All the old X-Men were gone except for Cyclops (though Jean Grey would quickly, and memorably, return), and they took Len Wein with them. Chris Claremont was credited as Wein's co-writer on issues 94-95, co-wrote the next issue with Bill Mantlo, and became the sole scripter for a very, very long time. [4]

The Legion of Ethnic Stereotypes

As part of a team with Dave Cockrum (94-107 and 110, returning not long after the Eighties began) and John Byrne (108-109, 111-143; for much of this time, Byrne was credited as co-writer), Claremont carved out an expansive corner of the Marvel Universe that made the rest of the company's mainstream adventures look tame. Fresh off of redesigning costumes on DC's long-running Legion of Superheroes, Cockrum brought a modern and exciting look to the characters, most of whom he designed.[5] Wein had established the new X-Men as a multiracial, multinational team, and Claremont leaned into this diversity hard. Granted, he did so with a stunning amount of stereotyping: every Japanese character has samurai blood and is obsessed with honor, Native Americans are always angry, and always announcing their tribal identity, while Irish, Scottish, and Southern characters' accents are transcribed in an almost indecipherable manner. But it was diversity nonetheless.

Notes

[1] The original comic series featuring the X-Men has undergone a number of name changes. It started out as simple X-Men, and was renamed The Uncanny X-Men with issue 114 (October 1976). In 1991, a second title was launched under the old name, X-Men (often referred to as "Adjectiveless X-Men), renamed New X-Men when Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely came aboard with issue 114 (May 2001). Various relaunches have recycled all three of these names over the years.

[2] In 2015, founding X-Man Bobby Drake (Iceman) came out as gay. Though fans had speculated about his sexuality for years (with some writers dropping the occasional broad hint), it's safe to say that he did not function as a "gay" character in the 1960s.

[3] Of course, this term was not used in relation to mutants until much later.

[4] X-Men 106 was a fill-in by Mantlo with Claremont's framing sequence that clumsily fit into the ongoing story. When Marvel reprinted the first decade of Claremont's X-Men in a monthly comic called Classic X-Men (later X-Men Classics), they left this one out.

[5] Cockrum developed the look for Colossus, Nightcrawler, Storm, Thunderbird, and the re-design of Jean Grey as Phoenix. Banshee, Cyclops, and Sunfire had already been established, while Wolverine had recently been introduced in an issue of The Incredible Hulk (drawn by Herb Trimpe but designed by John Romita, Sr.; he was co-created by Romita, Roy Thomas, and Len Wein).

Next: New Recipe X-Men

Welcome to the X-Men

The X-Men is all about "surviving the experience," whatever that experience might happen to be

Chapter 1

Surviving the Experience (Chris Claremont and the X-Men)

Welcome to the X-Men

There are worse ways to track the evolution of Marvel than focusing on the transformation of the X-Men from poor-selling cult favorite in the 1960s to bestseller in the 1970s, unstoppable franchise in the 1980s and 1990s, to the subject of a creative rebirth in the 2000s, victim of inter-corporate fighting in the mid-2010s, and yet another renaissance led by Jonathan Hickman in 2019. [1] Writing about Marvel in the 1980s without discussing the X-Men would be like writing about 1960s popular music while ignoring the Beatles. No doubt it's possible, but what would be the point?

The X-Men during this decade offer a wealth of material to examine, as well as a number of useful lenses through which to examine it. As a story about Marvel and the marketplace, the X-Men are a fascinating study in the development of a multi-book franchise despite the misgivings of the X-Men's central creative figure, the writer Chris Claremont. As the story of Claremont's seventeen-year run on the X-Men comics, it shows how the books changed along with the artists with whom he worked. Or as the tale of the balance of power between the man most closely associated with the franchise and the dictates of the company that published it, it is that rare case when the writer manages to incorporate nearly everything the editors impose on him while still maintaining his overarching vision. The story of the X-Men is also the story of a particular kind of storytelling: the apotheosis of Marvel's facility with soap-operatic long-term plotting, elevated by Claremont to near-Scheherazade levels of narrative complexity. And, last but not least, Claremont's X-Men succeeds thanks to his almost pathological preoccupation with depicting his character's inner lives as clearly expressed thoughts and speeches, and never more effectively than when he uses this approach in the service of exploring his female characters' response to trauma.

After Kitty Pride arrives at the Xavier institute for the first time, the cover of X-Men 139 introduces a line will stick with the franchise long after Claremont's departure: "Welcome to the X-Men, Kitty Pride. Hope you survive the experience!" Almost three years later, when, Rogue, up to that point a supervillain, is accepted into the fold by Xavier, the cover repeats the phrase, substituting Rogue's name for Kitty's. Havok later gets the same greeting, and soon it moves from the cover to the stories themselves: old X-Men use it on new X-Men, almost as if they were old fans greeting the next generation. The X-Men is all about "surviving the experience," whatever that experience might happen to be.

The Xavier School really needs to work on its marketing

It would take years for this theme to become central to the X-Men mythos. When the 1980s began, not only were the X-Men a seventeen-year-old property, but Claremont had been working on the book for five years. The first issue of X-Men with a 1980 cover date was number 132 ("And Hellfire Is Their Name!" pencils by John Byrne), not quite halfway through the most consequential storyline in the franchise's history. A little bit of backstory is in order.

Note

[1] Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely reinvigorated the line with their New X-Men in 2001. A decade later, the company tried to push The Inhumans at the expense of the X-Men. The Inhumans are 1960s Lee/Kirby creation with a small but devoted fanbase; though mostly guest stars in other comics, they had their own series and miniseries throughout the last three decades of the twentieth century (including Paul Jenkins and Jae Lee's remarkable 1998 12-issue series published as part of the Marvel Knights imprint). Though Marvel editorial has never confirmed it, the (temporary) retreat from highlighting the X-Men, along with the suspension of the publication of The Fantastic Four(the series that started Marvel as we know it), is widely understood to be the result of a dispute between Marvel's corporate owner, Disney, and Twentieth Century Fox. In the 1990s, when Marvel was experiencing significant financial distress, the company sold the film and television right for the X-Men and the Fantastic Four to Fox. The Fantastic Four films were not hits, but the first X-Men movie helped launch the current era of superhero dominance at the Multiplex. When Iron Man (2008) kicked off Marvel's incredible box-office success with Disney (and Disney's acquisition of Marvel the following year), the newly-formed Marvel Cinematic Universe could not use either of the Fox properties (and only managed to include Spider-Man after making a deal with Sony). Disney announced its acquisition of Fox on December 14, 2017. The deal became final in 2019, which also happens to be the year that Marvel recommitted itself to the X-Men line.

Next: All-New, All-Different

What Comes Next

Meet me back next week so we can talk about mutants