Secret Wars and the Rise of the Event Comic

As most of this book is about Marvel's artistic successes and near-misses, the rest of this introduction is meant to provide an overview of the general trends in the company's output, regardless of critical acclaim or disapprobation. Marvel introduced a number of elements to its storytelling and marketing that have had a huge impact on both the company and the industry. And in many cases, even if the initial Eighties output might be of dubious quality to readers who did not grow up with it, some of Marvel's worst creative decisions have their fans, and, more important, gave later creators material that could be transformed into something far better. This overview is also an opportunity for brief discussions of the many strong runs and fascinating experiments for which there is simply not enough room in this book.

Secret Wars and the Rise of the Event Comic

In the mid-1980s, both Marvel and DC would be forever changed by the introduction of line-wide crossover events, although the nature of these changes was different for each company. The financial success of each event incentivized the creation of further such events, with ramifications for the companies; storytelling that are felt to this day. But where the impetus for DC's Crisis on Infinite Earths came from concerns about the company's storyworld (Crisis was meant to simplify DC's complex system of alternate universes), Marvel's Secret Wars started with a failed toy deal and ended with a change in Spider-Man's costume that benefited comics sales and merchandising tie-ins. Without Crisis, DC's storyworld would be vastly different from what it is today. Without Secret Wars, Marvel wouldn't have the black costume that eventually merged with Eddie Brock to become Venom. Venom may have been the most successful new character of the decade, but in terms of the overall canvas of the Marvel Universe, a Venom-shaped hole would not in and of itself make today’s Marvel unrecognizable.

Nothing will ever be the same again! Except that it will be exactly the same again

In the medium-term, Secret Wars led to significant story beats, such as She-Hulk’s replacement of the Thing on the Fantastic Four, Colossus’s break-up with Kitty Pryde in X-Men, and the introduction of the second in a long line of Spider-Women. But the timeframe of the event meant that, unlike so many other such crossovers, it did not hijack ongoing Marvel titles. The set-up of Secret Wars was simple, if random: at the end of each of Marvel’s comics that came out in January 1984 (cover dated three months later, in keeping with industry traditions), the main characters are compelled to investigate the sudden appearance of a huge, alien construct in New York’s Central Park. They enter and disappear, only to reappear the next issue (in most cases; occasionally, it took two months). The entire twelve-issue miniseries takes place between these two issues, creating an unusual kind of suspense: we know that Spider-Man has a new costume, and that She-Hulk has replaced the Thing, but we don’t know why or how these changes happened. For that, we have to read the monthly installments of Secret Wars.

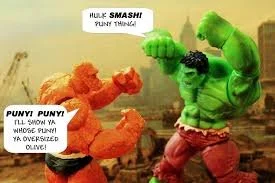

The series itself was never going to be mentioned in the same breath as Watchmen or Maus, but that was not what it was for. The premise could not have been simpler, if not simplistic. Most of Marvel’s heroes and villains are transported to a strange planet referred to as Battleworld, by an all-powerful, unseeing being who would become known as the Beyonder, who tells them: "I am from beyond! Slay your enemies and all that you desire shall be yours! Nothing you dream of is impossible for me to accomplish!" (Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars 1, May 1984, by Jim Shooter, Mike Zeck, and John Beatty.). The Beyonder would never coalesce as a character over the course of the series (a deficiency remedied in the sequel, though with terrible results), but that was fine. The Beyonder was a placeholder for the implied reader: however uninspired Secret Wars turned out to be, it is hard to deny the intrinsic fanboy appeal of the question, “Who would win in a fight between X and Y?” One can practically see the hands smashing together the action figures that initially failed to materialize. Secret Wars had a simple job to do, and it did it.

Who says comics aren’t profound works of art?

Along the way, Secret Wars actually managed to advance a few character beats. The Beyonder separates the characters into two camps, heroes and villains, with the X-Men quickly separating themselves out. But Magneto, who had been introduced as an antagonist in the very first issue of X-Men, was already on a slow journey of redemption in Claremont’s X titles. Thus all the characters in Secret Wars are surprised to find Magneto placed in the heroes’ camp rather than the villains’. In part thanks to the complications arising around Magneto, Secret Wars also pays attention to the fundamental differences between the X-Men and the Avengers as teams (the latter are acclaimed as heroes, the former are outcasts).

Next: You guessed it, Secret Wars II!