Syllabi

The Graphic Novel

IThis course examines the interplay between words and images in the graphic novel (comics), a hybrid medium with a system of communication reminiscent of prose fiction, animation, and film. What is the connection between text and art? How are internal psychology, time, and action conveyed in a static series of words and pictures? What can the graphic novel convey that other media cannot?

Syllabi from:

2021 (pdf) (docx) 2020 (pdf) (docx) 2019 (pdf) (docx) 2018 (pdf) (docx) 2017 (pdf) (docx) 2016 (pdf) (docx) 2015 (pdf) (docx). 2014 3 (pdf) (doc) 2014 2 (pdf) (doc) 2014 1 (pdf) (rtf) 2013 2 (pdf) (rtf) 2013 1 (pdf) (rtf) 2012 (pdf) (rtf) 2011 2 (pdf) (rtf) 2011 1 (pdf) (rtf) 2010 (pdf) (rtf) 2009 (pdf) (rtf) 2008 (pdf) (rtf) 2007 (rtf)

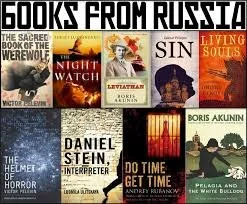

Reading Postsocialist Russia

This course examines Russian culture after 1991, through film, fiction, and television, as well as through the growing scholarship on postsocialism. Particular attention will be paid to the discourses of sexuality, crime, catastrophe, and nostalgia, as well as to the impact of economic and political change on both mass and elite culture.

Syllabus for 2014 (pdf) (doc)

The Unquiet Dead

Human life and artistic narrative can both be presumed to share one crucial defining feature: each always comes to an end. This course explores the persistent connections between various forms of storytelling (particularly fiction, poetry, film, and television) and imagined scenarios for life after death. While many of the most famous afterlife genres have strong roots in folklore (stories of vampires, ghosts, and zombies), one also finds stories that do not fit such conventional classifications. We will pay particular attention to the phenomenon of the posthumous narrator, a storytelling device that is deployed more often than many might think.

Syllabi from:

2020 (pdf). 2020 (docx). 2016 (pdf). 2016 (docx) 2013 (pdf). 2013 (rtf) 2011 (pdf) 2011 (rtf)

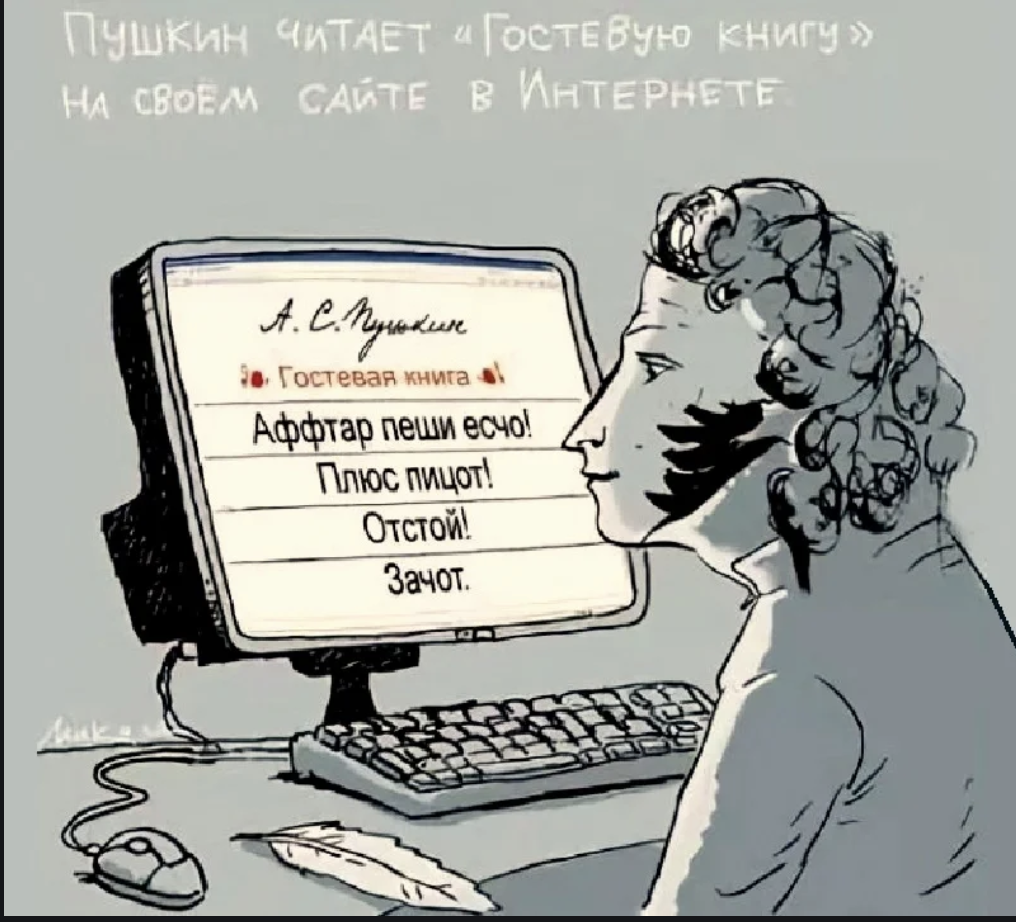

Narrative, Media, & Technology

Telling stories is a fundamental human activity, but the ways these stories are told depends upon the means in which they are created and transmitted. This course examines the role of technologies ranging from print, cave painting, comics, animation, and film, to hypertext, social media, and viral video. By looking at narratives in terms of the technological means and media that enable them, we remind ourselves that the gap between technology and culture is illusory, and that all artistic creation is technological by its very definition.

The 2017 syllabus features my favorite moment in my personal syllabus history: “I am obliged to include ‘learning outcomes,’ a concept I find worthless. Here they are.”

Syllabi for:

Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Reality

All fiction allows authors to create their own worlds; science fiction (SF) and fantasy bring this element of the creative process to the forefront. In this course, we will look at science fiction and fantasy as literary genres, examining their rules and the way in which these rules are broken. While we will confront a good deal of F & SF's most famous tropes, this course is less a historical survey than an introduction to SF's strengths and potential. What do science fiction and fantasy do that mainstream fiction does not? What is the connection between narrative form and the representation of reality?

Syllabi for:

Expressive Cultures: Words

What is literature or the literary? Is there a literary language that works differently from ordinary language? What is literary style and form? What does it mean to tell a story, and how is it different from telling a lie? What kinds of stories do we tell about our lives? Paying particular attention to questions of manipulation and emotion, we examine the status of fiction and representation through short stories, novels, and graphic novels by a range of authors.

Syllabi for:

2014 (pdf) (rtf). 2013 2 (pdf) (rtf) 2013 1 (pdf) (rtf) 2012 (pdf) (rtf) 2011 (pdf) (rtf) 2010 (pdf) (rtf) 2008 (pdf) (rtf) 2007 (rtf) 2006 (rtf)

Utopia and Apocalypse

By its very nature, utopianism is aggressively interdisciplinary: the search for a perfect world has resulted in a prose genre that straddles the boundary between fiction and philosophy, while the potential applications of utopian theory to political practice is the stuff of sociology, political theory, and experiments in “intentional communities.” Utopianism rather quickly spawned its skeptical counterpart, anti-utopianism (an argument with utopia), as well as a specific anti-utopian genre that has become a cliché of science fiction and film: dystopia (utopia gone wrong).

In this course, we will examine the development of the utopian tradition, primarily (though not exclusively) as a literary genre and philosophical thought experiment. Though defining the features of the genre will be an important component of our task, we will also examine the larger questions raised by utopian fiction: what is the impulse behind utopian literature? What is the relationship between utopia and the novel? How does time pass in utopias? How do we get from “here” (the imperfect world) to “there” (the perfect one), and how is this journey enacted in fiction? Why are the family, sexuality, and the role of women so central to the utopian tradition? How does utopian fiction at times inspire the reader to action, resulting in attempts to put fictional/philosophical models to the test (in communes, intentional communities, etc.)? What is the utopian conception of pleasure? Is there any place for the frivolous or the playful?

2013 (pdf) (doc) 2012 (pdf) (doc) 2011 (pdf) (doc) 2010 (pdf) (doc) 2003 (doc) 2001 2 (doc) 2001 1 (doc) 1999 (doc) 1998 2 (docx) 1998 1 (docx)

Major Russian Novels

This seminar is an exploration of some of the most important and fascinating literary works produced in Russia. While Russian literature is rich and varied, its welcome reception in the West has been based largely on a reputation for psychological depth, political/ideological engagement, and, most of all, a facility for engaging in the "big questions" in a fully-realized fictional context. While all of these aspects will be treated in this class, we will also pay attention to those aspects of the Russian literary tradition that do not fit this model: works that deal with the prosaic aspects of everyday life as well as those that engage in fantasy, magic, and the supernatural. While we concentrated largely on the nineteenth century, by the end of the semester will have moved into the early Soviet period.

Science Fiction

All fiction allows authors to create their own worlds; science fiction (SF) brings this element of the creative process to the forefront. In this course, we will look at science fiction as a literary genre, examining its rules and the way in which these rules are broken. While we will confront a good deal of SF's most famous tropes (travel through time and space, artificial life, utopia and apocalypse), this course is less a historical survey than an introduction to SF's strengths and potential. What does science fiction do that mainstream fiction does not? Syllabi for:

2012 (rtf) 2011 (pdf) (rtf) 2010 (pdf) (rtf) 2009 (pdf) (rtf) 2008 (pdf) (rtf) 2007 (rtf)

Soviet and Post-Soviet Literature

In this course, we will examine some of the greatest literary works to come out of Russia in the twentieth century. Though nineteenth-century writers such as Dostoevsky and Tolstoy are better known in the West than their twentieth-century successors, the literature of the present century is remarkable for stylistic and thematic innovations that, while continuing the Russian literary tradition, explore territory unknown the “classic” authors.

Russia Between East and West

This course will trace a question that has troubled Russians for centuries: what is Russia? What does it mean to be “Russian”? Certainly, most nations engage in such soul-searching at one time or another, but Russia, thanks to special historical circumstances, has been obsessed with the problem of its own identity. Central to this issue is an issue that would appear to be more geographical than cultural: is Russia a part of Europe (the West), or of Asia (the East)? Or is it some hybrid that must find its own unique destiny? As we trace the development of this problem throughout Russia’s history, we will also become acquainted with the major characteristics and achievements of Russian culture, from its very beginnings to the present day.

Syllabi for:

2011 (pdf) (doc) 2008 (doc) 2007 2 (rtf) 2007 1 (doc) 2006 2 (rtf) 2006 1 (doc) 2000 2 (doc) 2000 1 (doc) 1998 2 (docx) 1998 1 (doc) 1996 (doc)

Slavic Science Fiction

All fiction allows authors to create their own worlds; science fiction (SF) brings this element of the creative process to the forefront. In this course, we will look at science fiction as a literary genre, examining its rules and the way in which these rules are broken. Focusing on Slavic science fiction raises particular questions: how does the relative lack of popular genres in late Imperial, Soviet, and Eastern Bloc cultures affect the status and form of science fiction? Why are utopia, dystopia, and the apocalypse so important to Slavic science fiction traditions? What are the literary roots and the defining characteristics of Slavic SF, and how does it differ from Western SF? What has been the impact of the specific historical experiences of Eastern Europe in the 20th-century on the development of Slavic SF?

Modernist Poetry

This course examines the development of modernist poetry as a set of interrelated, but semi-autonomous, international movements, all united by a self-conscious sense of novelty, rupture, and apocalyptic change. The movements studied here fall roughly into two camps: the radical modernists of the avant-garde (futurism, surrealism, dada) and their more moderate counterparts (acmeism, imagism), all of whom trace their roots back to a poetic school they professed to disdain: symbolism.

Conversations of the West

Note: this Gen. Ed. rubric is now called “Texts and Ideas,” which is a step in the right direction.

In this course, we look at foundational texts ranging from antiquity through the early twentieth century, with a special focus on human conceptions of time and history. Most of the texts we will be reading interrogate the beginnings of human history and the origin of the universe while also speculating about the end of the world and the kingdom of heaven. Over the course of our readings, we will try to investigate this transhistorical insistence on conceiving of the world in terms of its origins and its endings. While this question will provide some of the focus for the course, the texts have also been chosen for their significance in the development of human thought and intellectual history.

Contemporary Central and Eastern European Literature

This course will provide an eclectic survey of works from Poland, the former Czechoslovakia, the former Yugoslavia, and Hungary. As the previous sentence suggests, it is difficult to come up with a term that unites these various traditions; as a rubric, "Central and East European Literature" is simply one of the least infelicitous of possible compromises. Our survey focuses on works produced in the last fifty years, a period which, for some of the nations involved, describes the rise and fall and rise of the state.

Though questions of politics and ideology inevitably arise when reading literature that reflects the totalitarian experience, such issues will not be the primary concern of this course. Rather, we will examine a wide range of questions regarding culture, philosophy, and the aesthetic: What does it mean to write in the tradition of a "minor" literature? What is the effect of writing in exile, or of writing in a foreign language? How do these authors turn their "marginal" status to their advantage? What is the impact of the Second World War on their writing? How do certain authors blur the boundaries between autobiography and fiction, and does this lend their work a greater claim to “authenticity”? Is there a "Central/East European" aesthetic or approach that unites these works? To what extent can these works be considered "postmodern"? How does looking at the literature of the last fifty years through a "Central/East European" lens change our approach to the postmodern?

Syllabi for:

Russian Popular Culture: The Twentieth Century

This course provides both a broad survey of the main trends of Russian popular culture throughout the 20th Century and an in-depth analysis of the forces and ideologies that helped shape these trends. Before the Revolution, the rise of an urban bourgeoisie and working class had developed a thriving “boulevard” culture, appealing to the tastes of the widest possible audiences in order to generate income. The Bolsheviks saw mass culture as a way of educating and transforming the population, and therefore did their best to use film, fiction, radio, television, and poster art to help create the “new Soviet person.” Yet Soviet mass culture was equally influenced by popular tastes, resulting in popular entertainment that was neither strict Socialist Realism nor the product of a free market of ideas. From perestroika on, Russian popular culture has gone through an enormous upheaval, thanks to the collapse of censorship, the pressures of market forces, and a flood of cultural imports from Europe and especially the United States. The second half of this course looks at the last two decades of Russian culture in the twentieth century, paying particular attention to the themes and problems that are most prominent.

Syllabi for:

Research Methods and Critical Theory

This course is intended to serve as an introductory to some (but by no means all) of the major trends in twentieth-century critical theory, and also to help incoming graduate students develop the research skills that are essential for any kind of advanced scholarly work. While most of the readings and assignments appear to be geared towards particularly literary studies, I contend that the analytical skills and critical stances exemplified by these readings can inform any interpretive activity.

In addition to reading purely theoretical texts, we will also be analyzing recent scholarly articles written by prominent and up-and-coming Slavists in order to understand exactly what goes into a well-wrought essay or article, to see how an argument is developed and supported, and how theoretical texts can be used in non-theoretical articles. We will also pay attention to these articles’ flaws, which can be equally educational.

Syllabus for 2000 (doc)

Russian Modernist Fiction

In this course, we will examine selected works of Russian modernist fiction, from the years immediately preceding the Revolution (Bely) through the early 1930s (Platonov, Kaverin), paying special attention to the most productive and troubled period in Russian fiction this century: the 1920s. Though most of our texts will deal with both Soviet life and Soviet ideology in one way or another, we will also be reading fiction by emigré authors (Nabokov).

Syllabus for 1998 (doc)

Sex and Gender in Russian Culture

In this course, we will investigate the categories of sexuality and gender in Russian culture. By “sexuality” I do not mean specific sexual practices, but rather the system that was developed for discussing (and regimenting) sexual expression. “Gender” is used not as a synonym for biological sex, but as a socially constructed category for interpreting biological sexual difference. Our focus on sexuality and gender will cause us to examine the concepts of masculinity and femininity in Russian culture, as well as the changing structure of the family in Russian life and art. Other recurring themes include homoeroticism and the connections between political and sexual rebellion.

Russia provides a unique opportunity to examine such issues: not only does Russia straddle East and West both geographically and culturally, but Russia has also been the object of numerous conflicting stereotypes, both self-selected and externally imposed. Russia is alternately viewed as a matriarchal society composed of strong women and “superfluous” men or a stubbornly partiarchal order in which women’s subservient position is masked by rhetoric and chivalry. Similarly, Russia has been at times perceived by foreigners as the land of libertinism and free love (particularly in the 18th Century and the 1920s), and yet the notorious declaration of the perestroika era that “we have no sex” points to a long history of asceticism.

Finally, the experience of Russia in the twentieth century can be viewed as the failed attempt to put radical theory into everyday practice, a grand scheme of social engineering that had the family unit as one of its primary subjects. The result is the common perception that Russia lived through “feminism” with disastrous consequences.

Syllabi for:

Russian Literature in Translation: The 19th Century

In this course, we will read a broad selection of the major works of nineteenth-century Russian literature (excluding poetry). Issues of style, theme, narrative technique, and literary movements and genres will be central to our examination of these texts, but we will also take special care to read the works in their historical and cultural contexts. This involves more than just lectures on the background of the various writers and movements; we will repeatedly turn to the philosophical debates that lie at the heart of so many Russian novels and stories: the polemic between Slavophiles and Westernizers, the problem of the "superfluous man" (and his foil, the strong Russian woman), the decline of the aristocracy, the generation gap between "fathers and sons," and, of course, the "Russian soul." Though the treatment of these themes is certainly linked to the particular historical moment of nineteenth-century Russia, many of the issues themselves are universal.

Modern Russian Culture

After gaining world-wide attention during the nineteenth century, Russia continued to be a major source of cultural production in the twentieth, but with a difference: Russian history has once again resulted in a culture that is both familiar and alien to Western observers. Specifically, the Soviet experiment was designed to produce a different kind of human being: the New Soviet Man. We will trace the cultural representation of this "new man," who, if he existed at all, ultimately strayed far from his theoretical model.

Soviet Fiction of the 1920s

In this course, we will examine selected works of Russian fiction that date from the formative period of Soviet literature and ideology, the 1920s. The 1920s represent a unique moment in Russian, if not world, history: after years of radical ferment, Russia finally had the opportunity to put into practice the social theories that had captured the attention of a significant portion of the intelligentsia. The first decade after the revolution held out the possibility that the gap between theory and practice might at last be breached.

This seminar treats the attempts of several Russian authors to explore the relationship between revolutionary theory and everyday life in works of prose fiction. One can argue that literature is no closer to "real life" than any social theory, and yet fiction can be used as a model of reality, a laboratory in which ideas can be tested under controlled conditions. Whether or not the authors themselves saw their work this way, the critics and the government certainly did: writers were alternately condemned or praised for the words and actions of their characters.

Syllabus for: 1993 (docx).