Becoming Russian outside of Russia

The early proponents of the global Russian idea are clearly putting their emphasis on the global, but the term that proves far more vexed, and also more potentially productive, is "Russian." The English word "Russian" has shown itself to be far more elastic and capacious than the Russian word "русский." The Russian adjective (also substantivized as a noun) is an exact match to the English term primarily when referring to the Russian language ("русский язык"); otherwise, the adjective used to refer to things or people connected with Russia as a country ("Россия") is "российский." As mentioned earlier, the corresponding noun for citizens of the Russian Federation is likewise derived from the country's name: россианин. One of the great ironies of the Soviet Jewish emigration is that Jews left the Soviet Union ostensibly because of discrimination facilitated by the country's rigid classification system; Jews were considered a "nationality," and therefore the infamous Line Five of their internal identification documents declared them Jews. In Russia, Jews, Tatars, Germans and any other people who were born and raised in Russia but not of specifically Russian (Orthodox/Slavic) descent are, by definition, not Russian. But Soviet Jews (and, indeed, virtually any white man or woman born in the USSR) immediately become "Russian" in their host countries.

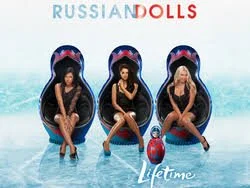

This was always great fodder for jokes, and in 2011 rendered a failed American reality show almost nonsensical to observers back in the Russian Federation. "Russian Dolls" has the distinction of being canceled almost as soon as it was aired, but for Russian speakers outside of America, its attempt to trade in "Russian" stereotypes was a bizarre misfire: virtually ever single "Russian Doll" was a Russian or Ukrainian Jew. In turn, these women, when speaking in English, always referred to themselves and their families as "Russian" (even to the point of musing aloud as to the likelihood of their parents accepting their marriages to men who weren't "Russian.") [1]

However bad you think this show might have been, it was actually much, much worse

In nearly every possible respect, the "Russian Dolls" are the antithesis of the global Russian ideal: narrow, provincial, and crass, they correspond much more closely to the archetype of the sovok (or even worse, to decades of Russian ethnic humor). But their utterly deracinated, deterritorialized deployment of the term "Russian" is instructive. In the New York context, if fits in perfectly with a tendency to use language as a shorthand for ethnicity (the “doll” who breaks off her relationship with a 'Spanish" man was almost certainly not dating someone who spoke Castilian and hailed from the Iberian peninsula).

In turn, the snobshchestvo's adoption of an English term to describe their identity is a rejection of everything narrow and exclusionary within Russian-language ethnonyms. In choosing English, Global Russians cast off the baggage with which the term "русский" simply cannot part. A Snob contributor named Aleksandr Goldfarb can comfortably muse about whether or not he is a global Russian in a way that he cannot consider his status as any sort of "русский." In Russian, the phrase "Aleksandr Goldfarb is Russian" ("Александр Гольдфарб--русский") inevitably sounds like an ethnic joke in search of a punchline.

The appeal of a more capacious word is quite clear. The official term "Россианин" ("Rossianin") is stilted and formal, and as one commentator on Snob puts it, the word sounds as alien as "Марсианин" ("Martian"). The same commentator points out that in English (and in many other European languages) one can quite comfortably refer to a "Russian of Polish descent," but the same locution sounds ridiculous in Russian. This commentator's name? Iraklii Buziashvili.[2] This is a point any Russian speaker could make, but if the speaker's name is Ivan Petrov or Mikhail Ivanov, it is a safe bet that he would be less likely to bother.

As a self-selecting group, the members of the snobshchestvo are much more likely to see these issues as relevant. The last thing I wish to do is comb through the names of contributors and commenters in search of Jewish, Georgian and other non-"Russian" names, which would be problematic and offensive for so many reasons. But even the most cursory glance at the site suggests that ethnicity is at least as strong a motivator for entertaining the notion of "global Russianness" as is mobility or social class.

Next: The Diaspora Beings at Home

Notes

[1] For an excellent analysis of Russian Dolls, see Chapter One of Claudia Sadowski-Smith's The New Immigrant Whiteness: Race, Neoliberalism, and Post-Soviet Migration to the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2018

[2] Russian speakers would immediately recognize this as a Georgian name.