Moscow Does Not Believe in Yaoi

The Dima Yakovlev law made its way through the parliament at roughly the same time as the gay propaganda law (with only six months separating Putin's signature on each). In both cases, the alleged concern over the fate of Russia's children could involve both fear for their development into adulthood and anxieties over Russian demographics. The demographic concern is a fascinating case of displacement: whatever population problems Russia might face, it is patently absurd to blame them on either foreign adoption or Russians who identify as queer. Straight Russian couples are choosing to have fewer children for all the reasons birth rates have dropped throughout Europe, exacerbated by an unpredictable economy and shortage of affordable housing. Linking demography to queerness and foreign adoption makes it look as though the state has found a way to fight an intractable problem, while also taking advantage of popular prejudice for political gain. To paraphrase the common disclaimer, no actual children have been helped during the development of this propaganda campaign.

Russia's rhetoric of child protection may look as though it is focused on the future, but, as is so often the case with knee-jerk social conservatism, it is more about an unwillingness to part with a particular view of the past. It is a pathologization of an otherwise predictable generation gap: the children raised in post-Soviet Russia have different experiences, pastimes desires, and values from those of their parent's and grandparents' generation. But in the years leading up to and following the passage of these laws, deviation from the norms of the past is explained as the result of the malign influence of the West, which is deliberately trying to undermine Russia's traditional values.

The gay propaganda law initially targeted cultural productions whose audience was presumed to be children, but slightly less than a decade after its passage, the law was amended to remove the distinction between children and adults. This fact might support the "slippery slope" argument, that any censorship to protect children will inevitably spread to adults. But it also suggests a state-inspired infantilization of the entire population: no one is mature enough to be exposed to this dangerous content. This infantilization, in turn, proves to be another manifestation of Soviet melancholy, as the inciting incident was perceived as an assault on Russia's (Soviet) past, while also echoing the Western conservative fanboy's complaint about updating their favorite IP (An all-female remake of Ghostbusters means "They're raping my childhood"). Adults had to be protected because now even their childhoods were no longer immune the lavender menace.

The melancholic nature of the fight against gay propaganda became particularly clear at precisely the moment the law expanded its scope to include adults. In December 2022, after nearly a year of bombings that killed scores of Ukrainian children and battles that turned teenage Russian recruits into cannon fodder, official Russian public opinion confronted an outrage against the very idea of prelapsarian (i.e., Soviet) childhood innocence: a gay romance novel entitled Pioneer Summer ("Лето в пионерском галстуке").

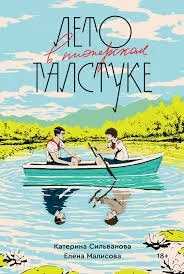

Pioneer Summer is the work of Katerina Sil'vanova and Elena Malisova (pseudonyms for Ekaterina Dudko and Elena Prokasheva), and is now available in an excellent English translation by Anne O. Fisher . The co-authors began releasing their novel in installments on ficbook.net in 2016; the book is often referred to as "fan fiction," although this term can be misleading to outsiders. Summerappeared in the "Originals" section, which hosts amateur writing that does not use a preexisting fandom. [1] In 2021, it was published by Popcorn Books, a Russian publisher that, in its three years of operations, had begun to make a name for itself in the world of YA literature, as well as for featuring books on queer themes. Summer was a surprise hit; by October 2022, it had sold 250,000 paper copies along with thousands of ebooks. A sequel, What the Martin Does Not Say ("О чем молчит ласточка") had already been published in August of that year. These books are the prose equivalent of the popular Japanese manga genre called yaoi: romantic stories about boys in love, usually written and read by women.

Think of the children! But not like that!

The book had all the ingredients of a Russian moral panic: gay romance, a less than reverent attitude towards the Soviet past, teenagers, concerned "experts" and pundits, and, of course, the Internet. Young readers made countless teary TikToks about how the book made them feel, leaving their elders perplexed by the phenomenon. Even worse from the point of view of Soviet traditionalists, the book appeared on the eve of the one hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Young Pioneers. It is unlikely that this was planned; if it were, the book would have come out in 2022, not 2021, and, in any case, it was written and posted on ficbook.net years earlier. But the conspiratorial mindset leaves little room for chance: Popcorn Books was trying to undermine respect for a beloved Soviet institution.

The fallout for those involved with the novel's publication was predictable: the authors have been declared "foreign agents" and were obliged to flee the country, while Popcorn Books, after being charged with violating the gay propaganda laws, was purchased by a new owner, who has declared his hostility to all things LGBT, and is trying to sell off the business. But the furor around the book itself was somewhat surprising. No one could have expected Russian cultural conservatives to welcome a gay romance novel, even one bearing the "18+" warning that was supposed to protect it from the original version of the gay propaganda law. The condemnations of the book often included casual assertions that the minimum age warning label did nothing to stop children determined to get their hands on such material

The vitriolic attacks on Summer are, of course, homophobic; at this point, that is a given. But they also engage in a strange kind of temporal collapse, reducing both Russian history and the human lifespan to a timeless singularity. In a Telegram post on May 25, 2022, Zakhar Prilepin, a writer famous for his xenophobic and neofascist views who would go on to be severely injured in a 2023 assassination attempt, raged against Popcorn Books (a name he compared to "Porno Books"), declared that he would like to burn down their offices (at night, when no one was there). And added:

As they say, what are the guys [at war] fighting for?

We must pass a law to protect our national Soviet symbols: the red banner, the red tie, the paintings and sculptures of real and cult heroes of that period. Otherwise, the number of people ready to use them for mockery grows greater and greater. (https://t.me/zakharprilepin/10747)

Somehow, a revisionist take on Soviet childhood could undermine the war effort by Russian young adults, while the Soviet past itself is now thoroughly assimilated to both Russian history and the Russian present. The conspiratorially-minded film director, blogger, and honey-voiced crank Nikita Mikhalkov also sees a story about a gay romance forty years ago as an attack on Russia today:

You have to be blind or an enemy not to see. How can we at the same time wage a serious, bloody battle against Nazism, against the rebirth of fascism in the center of Europe and at the same time the values of this same Europe that we're trying to battle with our own hands right here foster. And all during the hundredth anniversary of the Pioneers.

These screeds wrap homophobia, "Nazism," and the militarization of Russia into one ideologically clear package, all pointing to a lost paradise of Soviet childhood innocence and clarity of purpose. It was bad enough that "gay propaganda" could undermine the morals of today's youth, but absolutely unacceptable to project it onto a bygone age whose centrality to Russian political and cultural discourse has become all too clear since Putin's return to office.

Note

[1] This makes Summer different from the most famous example of fan fiction becoming commercial success, E. L. James' Fifty Shades of Grey. Fifty Shades started out as Twilight fan fiction, but the author removed all references to Stephanie Meyer's world to make it stand on its own. The authors of Summer did not have to take this extra step.

Next: "Little Russians:" Ukrainian "Orphans" and Their Russian Guardians