Heroism as Hospice

This a series whose second issue begins with a "highdive," the Horde's practice of forcing human captives out of airlock while in earth orbit: the new recruits look up to see streaks of light falling in the sky, each one a human body burning up upon re-entry. The Horde themselves wear human fingerbones and ears as jewelry, the visible reminder of their parasitical habits (they can't get enough of Earth's entertainment, chocolate, and human suffering). In fact, the Horde's consumption habits provide one of the keys to understanding just how Strikeforce: Morituri works: set nearly a hundred years in the future, all its characters, both human and alien, are at least in part defined by their relationship with twentieth-century popular heroic entertainments and their twenty-first century legacy. The fact that Harold, the initial viewpoint character, is engaging in the exact same form of wartime journaling as his The 'Nam counterpart is a happy accident, but it demonstrates that, at least in form, Strikeforce:Morituri is borrowing from war genre traditions. But beyond the first-person narration, Strikeforce: Morituri is reacting much more pointedly to the tropes not just of superhero comics, but of 1980s Marvel storytelling while it is still evolving. [1]

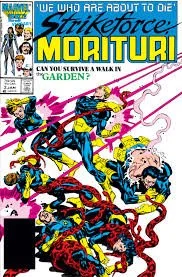

After all, not just anyone can go through the Morituri process, survive, and gain superpowers. The only viable candidates are those who happen to have the right genetic markers, and such candidates are few and far between. If contemporary readers of the first issue did not already notice the overlap with Marvel's most successful franchise, the X-Men, then the second issue made the comparison impossible to ignore. The cover shows all six Morituri candidates wearing identical blue and yellow form-fitting costumes, fighting snakes and lasers under the heading, "Can you survive a walk in the Garden?" Their clothing may not be identical to the traditional X-Men training uniforms (at that point still worn by the New Mutants team), but they were certainly close. The "Garden" in question is a transparent nod to the X-Men's Danger Room, where the mutants undergo combat simulations that are meant to test them without harming them. The Danger Room's safety protocols had a nasty habit of failing at opportune moments, a plot device that injected an element of risk into an otherwise stale X-Men scenario. [2] The Garden is Gillis's critique of both the Danger Room in particular and superhero comics in general: it is designed not to hone the Morituri's abilities, but to bring them out of latency by subjecting the volunteers to near-lethal stress. The team's minders have agreed to a cruel, potentially fatal scenario justified by the exigencies of wartime. In plot terms this makes sense, and continues to elevate the stakes of Gillis's fictional future, but it also turns the leaders of Project: Morituri into surrogates for the creators of Strikeforce: Morituri. The characters must be tortured because the genre itself demands it. And this is only one step away from the recognition of the reader's own complicity: we read Marvel books about physically and emotionally tormented super-teams because the stories of their suffering give us pleasure. Small wonder that two out of three of the second generation Morituri had powers involving emotional manipulation: "Scatterbrain" projected a broad range of emotional states, while "Scaredycat" projected only fear). Within the story, their powers crudely enact the effects the comics themselves were supposed to create.

Total Danger Room rip-off! Marvel should sue! Oh, wait…

At the same time, Strikeforce: Morituri is free to indulge the contemporary superhero preoccupation with death unburdened by the near-immortality of corporate IP: Gillis and Anderson have created a story that builds readers attachments to characters while also maintaining the protagonists's fungibility: had it continued in near-perpetuity, Strikeforce: Morituri would have been an almost-perpetual motion machine for the creation and destruction of new characters.

While the book's main theme is undeniably mortality, Strikeforce: Morituri is also about the affective feedback loop binding the comics, their creators, and their readers. Harold, the viewpoint character whose sudden death in Issue 6 undercuts readers expectations that the center of narrative focus is likely to last until the end, is motivated not just be righteous anger at the alien invaders, but also by the superhero comics he read as a child. Over time, Gillis makes clear that these comics are not just a generic stand-in for the ones produced in our world; they are, in fact, Marvel Comics. As an adult about to volunteer for the Morituri process, Harold reads and re-reads the sequential adventures of the Black Watch, the now-dead team of Morituri prototypes. These comics-within-a comic are wartime propaganda, like Captain America during World War II. But they also introduce an element of optimism, however metafictional: despite the perennial, predictions of the industry's impending demise, ninety years from now, comics are still going strong. The Morituri themselves even get their own in-universe comic: a hacky, over-the-top melodrama whose emotional, expository dialogue is a cross between Stan Lee and Chris Claremont.

Nor are comics the only medium that is thriving: one of the pleasures of Stikeforce: Morituri is seeing the story refracted through multiple media. In addition to a children's animated show, Hollywood has created a live-action version to entertain and uplift earth's population. One of the actors who played a first-generation Morituri is so inspired by the original model that he himself volunteers for the process, joining the second generation. Strikeforce is almost as media-saturated as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, repeatedly employing television broadcasts to bring the characters (and the readers) up to speed. Appropriately for a superhero comic that interrogates its own form, Strikeforce is both a futuristic extrapolation and post-apocalyptic reclamation of late twentieth-century mass culture. The futurism is not particularly novel (television is now holographic), but the series' main antagonists are unimaginative scavengers who collect and consume cultural, economic, and (literal) human resources with little regard for their original intent. They cannot get enough of the Earth's detritus; their near-addiction to chocolate (junk food!) is a perfect example of their culture of consumption. Their ships are full of looted alien artifacts that they do not even attempt to understand (and that will eventually lead to their downfall). Theirs is a cargo cult in reverse: instead of waiting for ships to bring magical cargo to their shores, they fly their own (stolen?) ships to plunder and pillage everything they could want from more creative civilizations. The very name that humans use to describe them is doubly evocative: literally, it defines them as an endless, undifferentiated barbarian mass, but homophony also suggests one of their essential characteristics: the Horde are hoarders. Thus they are not just savage, genocidal monsters: they are bad fans.

Next: The Triumphant Downfall of Hank Pym

Notes

[1] Add footnote for José Alaniz' great chapter on this series.

[2] Nearly two decades later, Joss Whedon's Astonishing X-Men would reveal that the Danger Room was sentient, which not only meant that Professor Xavier was knowingly enslaving a thinking being for his own purposes, but that the room's malfunctions might also be thought of as manifestations of its resentment.