Neither Seen Nor Heard

(Originally posted on November 16, 2015)

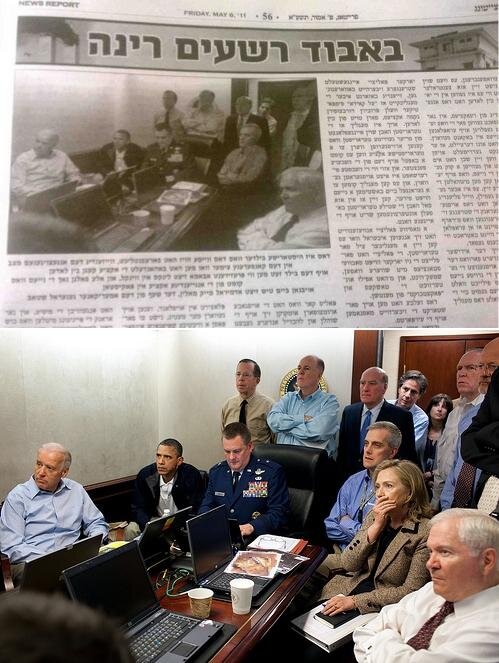

You can tell a lot about a community based on what it bothers to censor. By the same token, if you do not know enough about the community doing the censoring, then the choice to ban or expunge looks almost random. The 2011 photo of then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton sitting in the White House Situation Room surrounded by a number of male officials looks inoffensive, at least as an image; an Orthodox Jewish newspaper’s excision of Clinton from the picture only makes sense in light of a prohibition on displaying the female form (even one as demurely pants-suited as Clinton’s).

If we turn to contemporary Russia, the 2015 decision to prevent screenings of the film Child 44 looks only somewhat less puzzling. The story takes place at the height of the Stalinist repressions; while there has been a great deal of whitewashing of Stalinism in recent years, pointing out that people were arrested and killed for no good reason is still not forbidden. [1] The plot involves the hunt for a serial killer who has been murdering homosexual men (all closeted by definition); same-sex activity remains legal in the Russian Federation, and if the serial murder of men who have been engaging in sex with each other on the down low constitutes “gay propaganda,” one wonders how many young people can be expected to take humiliated murder victims as their romantic role models. Could the Minister of Culture perhaps unconsciously be conflating Child 44 with a gay rights group that, by pure coincidence, all but shares its name with the film: Дети-404 (Children-404)? Children-404 advocates for gay teens in a legal climate that renders all such advocacy virtually illegal, and takes its name from the error message “404—Page Not Found,” usually displayed when a website is no longer live (or, in the case of LGBT-themed sites, closed down by government order). While there is delicious irony in the juxtaposition of a story about gay victims of predators and an organization dedicated to help a juvenile population that has been redefined as the target of (gay) predators, irony alone gives no cause to ban a film.

Yet banned this film was. Partly, it was a matter of timing: Child 44 was to be released just three weeks before the 70th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany, and this particular Victory Day was obviously going to be a monumental celebration (the opening of the 2014 Olympics in Sochi had already set the aesthetic parameters for national historical festivals: solemn commemoration meets Vegas-style spectacle). The Russian Culture Ministry condemned “the distortion of historical facts and original interpretations of events before, during and after the Great Patriotic War." Speaking later to RIA-Novosti, Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky made a telling connection between the depiction of history and the country’s very sense of self: “It is important that we should finally put an end to the endless series of schizophrenic reflections of ourselves.” In other words, the film is bad because it is a Western distortion of the Russian past, and because it is a continuation of a Russian debate about the essence and fate of Russia. What looks like a contradiction is actually an inadvertent piece of insight about the current media landscape, in which Russia’s own cultural productions have to compete with Hollywood in the creation of an imaginary history for an audience that the elites cannot trust to come to their own conclusions. Indeed, in his condemnation of the (rather obscure) Western fiction that is Child 44, he invokes a narrative that has conquered virtually all national boundaries: the movie, he complains, portrays Russia as “not a country, but a Mordor, with physically and mentally inferior subhumans.” As we shall see in Chapter Four, The Lord of the Rings is something of a touchstone in recent contestations of Russian identity.

The point here is not to defend Child 44, which is based on an admittedly mediocre novel by a man with a very poor understanding of Soviet reality. In the book, author Tom Rob Smith sets himself a perverse task: to develop generically familiar tales of murder and its investigation against the backdrop of state violence on a massive scale. Smith has clearly read the English-language books about the notorious serial killer Andrei Chikatilo, along with a number of poorly digested potted histories of Stalinism and the gulag. He creates a totalitarian fantasyland based on the one lesson his reading afforded him: the most important thing under Stalin was survival. In his hands, Soviet citizens become cold, efficient survival machines, whose every action is the result of a carefully-weighed, logical decision that might be followed by a muted, unemotional discussion. The result is a staggeringly alien one-dimensionality of characterization, as if Dostoevsky's underground man had emerged from his isolation, spent a few years at the London School of Economics repenting his previous irrational ways, and now set out to apply rational choice theory to human behavior. At times, Smith's books depict a fascinating world, but I find myself wishing he had embraced the inherent fantasy of his vision, and, like Gregory Maguire in Wicked, moved his meditations on authoritarian regimes to the not-so-merry old Land of Oz.

If Child 44 (whether book or movie) does a bad job of reproducing Soviet life under Stalin, the question is: why? A number of very simple and plausible answers immediately come to mind: laziness on the part of the filmmakers, the aforementioned faults in the source material, and, most of all, an utter lack of a sense that there is anything in particular at stake. In other words, it’s just a movie. But Child 44 was portrayed as part of a Western plot to slander Russia (presumably at least in part by suggesting that homosexuals existed in the Soviet Union before America and Europe had had the opportunity to exert their pernicious influence). As in the case of the scandal a decade earlier, when Russian legislators were outraged that Dobby, the house elf who debuted in the third Harry Potter film, seemed to display a marked resemblance to Vladimir Putin, Western mass culture provides a useful straw man. In each case, the immediate assumption is that nothing is left to chance, and that Hollywood is, of course, taking its orders from the White House or the State Department. Russia’s fate, it seems, is to be the object of slander and conspiracy at all times. And the purveyors of this conspiratorial worldview see this victimization as a point of pride.

The crux here is far more than the tired question of representation and accuracy, nor should we stop at the simple conclusion that Russian governmental officials during Putin’s third term are unnecessarily touchy. Representation suggests something static or iconic, and is a category that is too dependent on external, often unverifiable notions of the true essence of the thing represented. If we deal in representations, we can too easily succumb to the dichotomy of “propaganda” vs “truth,” falling into the very sort of paranoid trap that I hope to investigate. Instead, I would frame the questions raised by the Child 44 incident in terms of narrative and interpretation. Part of the problem results from the narrative Child 44 appears to provide, but the larger issue is the narrative into which the making and marketing of Child 44 are all too easily assimilated. In each case, we find a question of plot.

I am by no means the first critic to point out that the English language provides endless possibilities for word play and interpretive flights of fancy based on the multiple meanings of the word “plot” (the events of a story as elaborated in a narrative vs. conspiracy). And if we want to ascribe explanatory power to this lexical coincidence, we must first reckon with the fact that this word play has no equivalent in the language that forms the subject of this book, i.e., Russian. The Russian language suggests other tantalizing possibilities, since the word for “plot/conspiracy” (заговор) is closely linked to terms for faith healing and magic spells. Rather than pretend that etymology has some sort of magical interpretive primacy, I prefer to admit upfront that I am simply taking advantage of the possibilities that English vocabulary affords. My book focuses both on the power of plot and narrative to model conceptions of Russia’s identity and fate and on the habits of conspiratorial theorizing that are the building blocks of so many of these stories.

Note

[1] For more on the role of Stalin in current Russian memory wars, see Nikolai Koposov’s Pamiat’ strogogo rezhima: Istoriia i politic v Rossii. Moscow: NLO, 2011. An English language overview of his argument can be found in Koposov, Nikolay, “The Armored Train of Memory": The Politics of History in Post-Soviet Russia.” Perspectives on History (January 2011). https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2011/the-armored-train-of-memory-the-politics-of-history-in-post-soviet-russia (last accessed on November 16, 2015). For more recent information, see Roland Oliphant, “The Growing Struggle in Russia about Historical Memory.” The Telegraph (May 6, 2015). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/11585936/The-growing-struggle-in-Russia-about-historical-memory-and-Stalin.html (last accessed on November 16, 2015). The government’s interventions in this regard have not been exclusively repressive (Anna Dolgova, “Russian Senator Introduces Bill Criminalizing Pro-Stalin Propaganda” The Moscow Times September 22, 2015. http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/russian-senator-introduces-bill-criminalizing-pro-stalin-propoganda/532375.html (last accessed on November 16, 2015). Nonetheless, given the campaign against anti-Stalinist non-government organizations such as Memorial, the writing does appear to be on the wall.