Epic Fail: Forging a Russian Past

When writers engage in this sort of ideological cosplay, they are nearly always collapsing time. Certainly, every futuristic utopia or dystopia inevitably bears the mark of its moment of composition; in the aftermath of the British enclosure of farmlands, Thomas More’s Utopia reflects on agriculture in a way that Zamyatin’s We and Orwell’s 1984 do not. Yet so many of the most noteworthy recent fantasies about Russia’s future are remarkably backwards-looking. In addition to Bykov’s focus on Khazars and Varangians in Living Souls, we also have the revival of the policies and mores of Ivan the Terrible in Vladimir Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik and Mikhail Yuriev’s Third Empire; the resurgence of serfdom in Tatyana Tolstaya’s The Slynx, and the resurrected threat of a Fourth Reich in both the multivolume Ethnogenesis series of young adult novels and, less centrally, in the future history Dmitry Glukhovsky began in the transmedia juggernaut Metro 2033. [1] Glukhovsky’s underground postapocalyptic Moscow subway even has a union of ring line stations calling itself the “Hanseatic League,” while the Sokolniki (red) line has become the overdetermined home of die-hard Bolsheviks. Geography may or may not be destiny, but it is an indispensable accessory.

All of this leaves room for a familiar and tedious historiographic debate: should Russian history be understood as a set of cyclical, recurring patterns whose regularity can be used for predicting the country’s future? Or is this merely an ideological construct (as well as a possible self-fulfilling prophecy)? Whether or not Russia is doomed to repeat its past, we, fortunately, are not doomed to repeat this debate. Instead, what is important is the persistent habit of seeing such patterns, of interpreting Russian history as if it were all part of a legible plan. Such a habit does more than just foster a sense of pessimistic resignation; it insists on the power of history for both the future and the present, rendering history always immanent.

Alternate history is a powerful tool in the conspiracist arsenal, allowing conspiracy to become the story of Russia, something of a postmodern national epic. Scholars of Russian literature will recall the Neo-Classicist preoccupation with the national epic in the 18th century: it was the one element of the classical constellation of genres that Russia could not provide. Certainly, Russia had folk epics, and, like most Slavic epics, these were stories of defeat rather than triumph. But there was no single unifying story that could serve as a cultural point of origin. Ironically, as soon as one contender appeared (The Igor Tale) it was haunted by accusations of forgery. Russian literature is hardly the poorer for it: would anyone really trade Pushkin or Dostoevsky for a Slavic Beowulf or Chanson de Rolande? But the Russian conspiratorial narrative offers a story that always reaffirms Russia’s role as the hero of history while emphasizing its status as the world’s victim or offended party.

Alternate history would then be a deliberate falsification that threatens to undermine the very foundations of a commonplace Russian self-perception. But in fact, the goal of alternate history is the opposite. Alternate history, by essentially lying about the nation’s past, is an attempt at strengthening Russian cultural and historical legitimacy. If history, understood as inevitably recurring patterns, takes on the function of national myth, the replacement of reputable history with out-and-out mythology ends up telling an even more compelling story than could be supplied by mere facts.

Again, this is the sort of mythmaking that is easier to spot in its natural habitat of pure speculation: one expects to hear about the origin of the world in sacred texts (the Garden of Eden), mythology (Odin’s construction of the world from the corpse of Ymir), and epic fantasy (the formation of Middle Earth by squabbling gods). Yet this obsession with origins is also found in myth’s more prosaic counterpart, utopia (where, often as not, politics and law take the place of divinity and magic). The radiant future of utopia is usually preceded and predicted by a Golden Age, with the point of origin and endpoint serving as bookends for the story of a fallen humanity reclaiming and reinterpreting paradise as part of a secular future history. The communist “withering away of the state" mirrors a posited primitive communitarianism; feminist utopia reinscribes a prehistoric matriarchy; and the imagined triumph of the white race reenacts an equally confabulated primordial Aryan purity. The imaginary origin legitimizes the imaginary endpoint.

Alternate history serves a similar function, but, in the cases I have in mind, at a more local level. The broader, international category of alternate history as entertainment is another matter, since the sheer novelty of a different historical outcome can be a sufficient source of textual pleasure. Russia has no shortage of this sort of story, but the high stakes for the Russian narrative become clear when alternate history makes the species jump from novels preoccupied with the rearrangement of historical fact to pseudo-scholarship whose organizing principle is the replacement of fact with fiction and the dismissal of all traditional scholarship as conspiratorial fabrication.

In this, as in most things, Russia is not unique in producing conspiratorial counter-histories. But, again, the current historical moment is crucial. Since the dismantling of the USSR, counterfactual narratives have flourished, and none more than the “New Chronology” product spearheaded by the renowned mathematician and stupendous crackpot Anatoly Fomenko. Following in the wake of a series of less-known attempts at chronological revisionism, Fomenko claims to to have proven mathematically that history as we know it is a vast falsification. His New Chronology is to history what Young Earth Creationism is to Biology and Paleontology: all of human experience has unfolded in a hypercompressed timeline. Prehistory began in the 9th century CE, Christ was born in the 11th century, and the New Testament was written after the Hebrew Bible. But wait, there’s more: Fomenko takes every opportunity available to him in order to combine a supposedly ancient city or even with a more recent counterpart. Thus Jerusalem was actually Constantinople, and “ancient” Greece was really medieval Greece. [2]

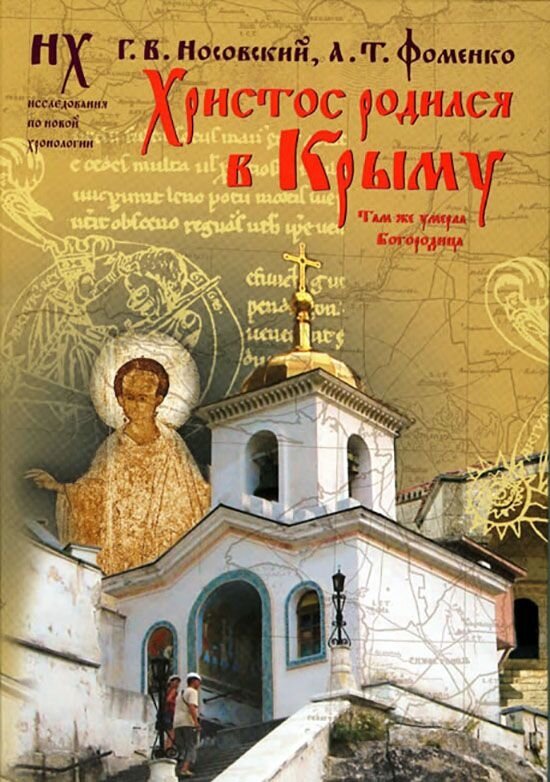

CHRIST WAS BORN IN CRMEA. AND THAT'S WHERE THE MOTHER OF GOD DIED, TOO.

When summarized, the scope of Fomenko’s historical revisionism is misleading. The purpose of Fomenko’s 30-volume work is to make Russia the hero of history. Marco Polo visited Yaroslavl, and the Scythians, Huns, Cossacks, Ukrainians, and Belarusians are simply parts of a mammoth Russian Horde. The title of a 2009 book composed with his frequent co-author Gleb Nosovsky puts it best: Christ Was Born in Crimea. And That’s Where the Mother of God Died, Too. [3] As with so much of the tendentious fiction we’re examining, Christ Was Born in Crimea would take on new significance after Putin’s national-authoritarian turn (along with skyrocketing sales). This is not to suggest that Putin and his advisers were turning to pulp fiction and lunatic fringe pseudoscholarship for direct inspiration, but rather that the margins of mass culture were a comfortable home for ideas that would later move to the mainstream. At the very least, it is a reminder that the policies of Putin’s third term, the seizure of Crimea, and the demonization of Ukraine did not appear out of nowhere.

Fomenko’s revisionism has roots going back to Soviet times (which, if we follow his mathematical contortions, probably took place during the first half of 2012). Russia, we should remember, invented the radio, baseball, and even The Wizard of Oz. But before we laugh dismissively at Fomenko’s ravings (or, if it’s too late, then after), it’s worth noting that the attempt to re-situate history within local and recent national boundaries looks rather…American. Christ’s birth in Crimea fits rather well with the Mormon claim that he visited North America after the crucifixion. And Fomenko’s assertion that Christopher Columbus was a Cossack may argue for a Russian claim to the New World, but it also reminds us of the problematic character of the entire Columbus story (“discovering” a continent where people had been living for centuries).

As world power latecomers, Russia and the United States share a tendency to see themselves as the heroes of history (and to spin conspiracy theories at the drop of a hat). But where America blunders forward in the narcissistic self-confidence of a people unconcerned with the past, Russia has historically been troubled by a preoccupation with origins and legitimacy. Fomenko’s narcissism is profoundly neurotic, and forms the basis of a counterhistory that must be seen as compensatory. Whenever possible, Fomenko’s alternate history rejects the very category of the Other. To call Fomenko’s project imperialist would be an understatement, as he subsumes territorial aggrandizement to semiotic expansionism. For Fomenko, the whole world is Russian.

Notes

[1] Given the Putin regime’s insistence on casting post-Maidan Ukraine as a Nazi revival show, these authors have clearly tapped into a powerful cultural script.

[2] Here I am relying on Marlene Laruelle’s blessedly compact summary of Fomenko’s main ideas in her article “Conspiracy and Alternate History in Russia: A Nationalist Equation for Success?” The Russian Review 71 (October 2012): 565-580. I have thus far made it through only three volumes of Fomenko’s collected works, with only limited motivation to forge ahead.

[3] The publisher’s description includes an unintentionally hilarious reassurance: “This book does not demand any special knowledge from its reader.” (Носовский, Г. В. и А. Г. Фоменко. “Христос родился в Крыму. Там же умерла Богородица.” Москва: АСТ, 2009. )