Form's Fallow Function: Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt

Without Watchmen, Kieron Gillen’s and Noah Wijngaard’s five-issue run on Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt would have no reason to exist. Far from a criticism, it is a statement that I imagine everyone involved, from the creators to the publishing staff at Dynamite Entertainment, would accept. Even by the standards of Charlton Comics, publisher of the original Peter Cannon stories, this character is as D-list as they come. After running for only 10 issues in 1966-1967, he was brought to DC along with Captain Atom and the rest. When DC editors were concerned that Watchmen would render their newly-acquired heroes unusable, they probably weren’t thinking of Peter Cannon. He was practically unusable on his own.

HE REALLY SHOULD RETHINK HIS POSITION IN RELATION TO THE TARGET

Still, the people at DC tried. Along with the other Charlton characters, he made a brief, forgettable appearance in Crisis on Infinite Earths (his face was obscured, and artist George Perez assumed he was a speedster). From 1992-1993, he headlined a 12-issue series written and pencilled by Mike Colins, made a few appearances with the Justice League, and disappeared for years.

WATCH OUT, PETER! BROWN PEOPLE!

DC had reason not to try very hard: Peter Cannon’s creator, Pete Morisi, retained the rights to the character even during the Charlton years; after the company’s bankruptcy, Morisi licensed Cannon to DC rather than selling him outright. Eventually, the license was picked up by Dynamite, where Steve Darnell, Alex Ross, and Jonathan Liu produced a 10-issue series from 2012-2013. This year, they gave it another try. With a comic named “Thunderbolt,” there is a temptation to say that Dynamite was trying to see if lightning could strike twice. But really, they were hoping that it would finally strike once.

Look on My Works, Ye Mighty, and Despair!

In writer Kieron Gillen, Peter Cannon finally found his Alan Moore. Well, technically, he’d found an Alan Moore before, but this one was going to let him keep his name. As Gillen makes clear in numerous interviews, the main draw to Peter Cannon is that he was the inspiration for Ozymandias. Gillen dutiful read all of Peter Cannon’s previous appearances, which must have taken at least three hours out of his day. Then he got down to work.

That work consisted of making and unmaking Watchmen, a task we have certainly seen before. But Gillen is different from the other creators we’ve dealt with so far: Grant Morrison, Len Wein, J. Michael Straczynski, and Darwyn Cooke are within a few years of Alan Moore in age. Gillen was born in 1975; the only other writer we’re looking at who belongs to his cohort is Geoff Johns (b. 1973). Eleven years old when Watchmen came out, Gillen was hardly the comic’s target audience, and an unlikely purchaser of any of its issues as they hit the stands. By the time Gillen came to consciousness as a dedicated comics reader, Watchmen would have been a given rather than an event.

Thus Gillen’s relationship to Watchmen is comparable to Moore’s connection to Marvelman: in each case, the writer is returning to a beloved comic from his younger days (that is, an old comic) and revising it according to his contemporary, adult aesthetic. This is not to deny the basic distinction of quality: most of Moore’s reclamation projects involve cultural trash (again, Marvelman, but also Supreme, the Charlton characters, and the early 1980s run of Swamp Thing), while Gillen faces the more challenging task of doing something creative and new with a source text widely considered groundbreaking. Like Morrison before him, he has to succeed where Before Watchmen failed. He must find a way to be revisionist without being superfluous.

His own success lies in the judiciousness with which he approaches his influences. Serious comics readers will immediately recognize what Gillen himself says upfront in a series of Peter Cannon annotations published on the Bleeding Cool website: each issue plays with a different style. The ultraviolent episode is his homage to Mark Millar. The “ordinary world” issue is a note-perfect reproduction of Eddie Campbell’s Alec stores (Campbell being a collaborator on another signature Moore project, From Hell). The stores contain little tributes to Morrison (“I see you!”), Warren Ellis (“Do you like bullet violence?”) , but most of all, to Watchmen.

A brief summary before we continue: Peter Cannon and his superhero colleagues (each a variation on the Charlton heroes) face an alien invasion that threatens Earth’s very existence. Cannon develops a strategy for victory, but then confides in his assistant and former lover Tabu that the invasion was clearly a ploy to unite a fractured world around a common threat, and that the only person who could have come up with such a plan was…Peter Cannon. But a Peter Cannon from an alternate universe. At this point, we see this other Peter (whom Gillen tends to call “Thunderbolt” in his essays and interviews, to distinguish him from “our” Peter), watching multiple TV screens like Ozymandias in Watchmen. In the second issue, Peter gathers his comrades together for a trip through the multiverse, ending in the Thunderbolt’s world.

In a direct echo of Jon’s murder of Rorschach, the superpowered Thunderbolt informs Test, Rorschach’s absurdist counterpart, that “This is a serious story” before disintegrating him. In Issue 3, Thunderbolt slaughters the protagonist’s entire team before pushing Peter through a window into another universe. Issue 4 sees Petert in a mundane, black-and-white world with no room for superhuman, until he finally makes his way back to Thunderbolt’s world. Thunderbolt needs him, because he is the only Peter Cannon who has figured out how to cross from world to world. Peter wins by giving Thunderbolt what he wants, but when Thunderbolt enters the space between worlds, he is torn to pieces. The surviving Peter Cannon returns to his homeworld, bringing along the antagonist’s analogue of Tabu (transformed into a robot long before the story began). Peter rekindles his love with his own Tabu and rejects the esotericism that had previously distanced him from humanity.

Visually, Peter Cannon never lets us forget Watchmen, with panels and entire pages formally reproducing or riffing on memorable moments in Watchmen, but it manages to do so without being tedious. One of the many mistakes of Doomsday Clock is the attempt to write this unauthorized sequel in slavish imitation of Moore and Gibbons, straining to write prose that sounds like Moore’s but is not Moore’s.

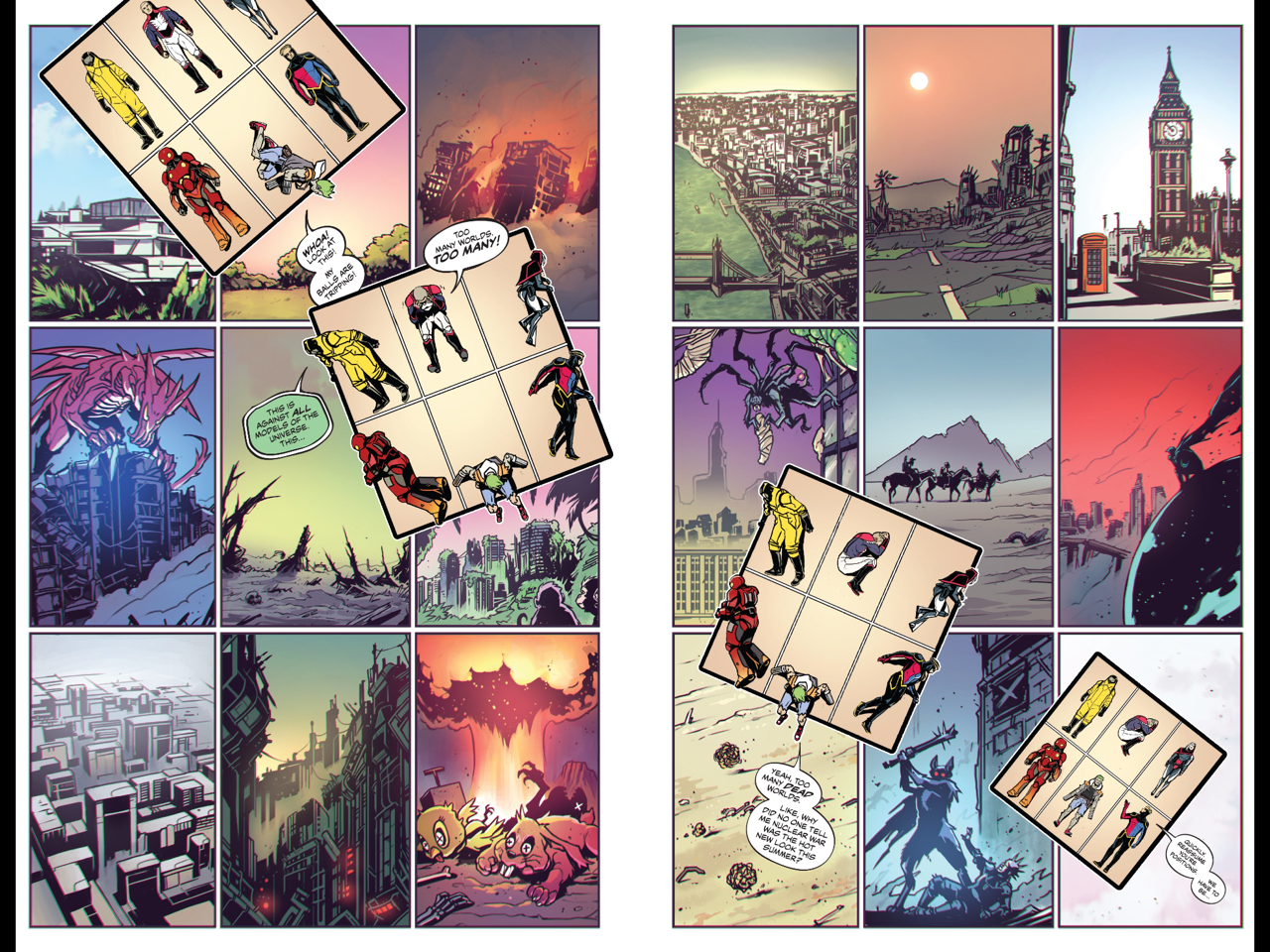

Instead, Gillen and Wijngaard judiciously mix obvious stylistic riffs on Watchmen with visual elements that would have been out of place in Moore’s and Gibbons’ graphic novel. The nine-panel grid from the 1980s series (more about that in a moment) contains brightly-colored scenes that would never have fit in with Watchmen’s somber pallet, and the playful appropriation of different art styles (such as that of Eddie Campbell) is a departure from Watchmen’s unflagging visual consistency. In fact, it is precisely at the moments whose layout most obviously copies Watchmen that the almost day-glo coloring is so jarring (as when the evil Thunderbolt pushes Peter out the window in issue 3, or when Peter comes back through that window two issues later).

And of course, in both Watchmen and Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, this broken window is a visual reminder of the importance of frames to the very essence of comics. Watchmen, we recall, makes its argument about comics through its constant emphasis on comics form, drawing the reader’s attention to the ways that page layout structures both time and space. Like Pax Americana, Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt does battle with Watchmen on the latter’s home turf, expanding on Watchmen’s formal devices to make its own point about time, space, comics, and even the human condition. Where Pax Americana tweaks Watchmen by subtracting one panel from the famous nine-panel grid, Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt recommits itself to the nine-panel structure, to make points of its own.

Off the Grid

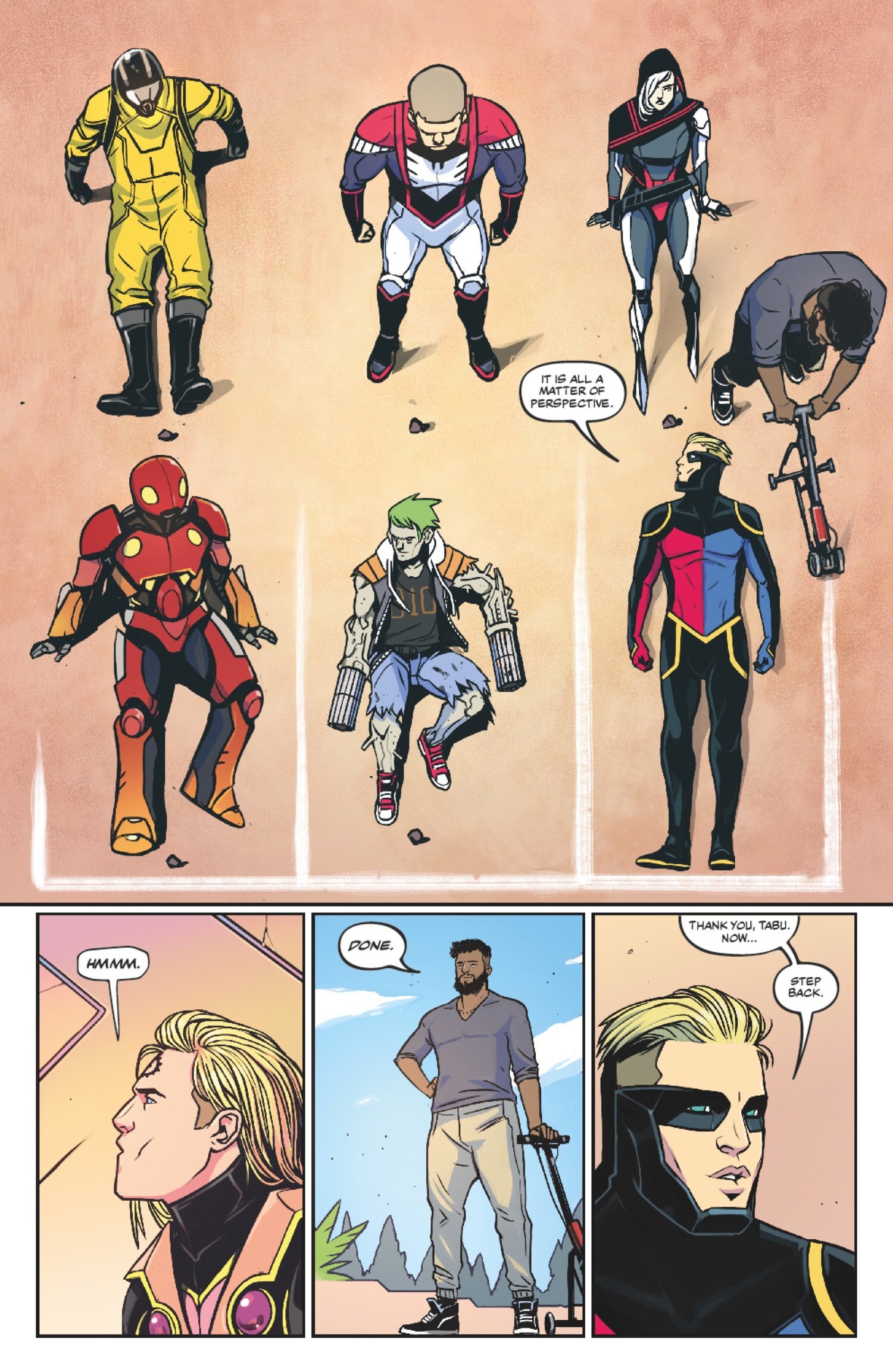

Peter Cannon invokes the power of the comics form, but in order to call into question the very value of a formal focus. When the protagonist begins to demonstrate his dimension-crossing method to his colleagues, the witch Baba Yaga declares,

“This is beyond my mysteries.

“This is not magic.

"This is…

Formalism.”

Whereupon all six heroes lie down on the ground as Tabu draws rectangles around them with a white paint roller. The resulting six-panel grid looks like two-thirds of a Watchmen page, but also like a display case for action figures. The comic makes clear that they are transported through dimensions by a comics page cut loose from its bindings. First we see an entire page that is nothing but a blank nine-panel grid with the words “AND THEN…” in the middle, followed two more pages of such grids another. in which each panel shows a different world, while two six-panel grids are superimposed, giving the impression that they are traveling across the dimensions and the page. In the second six-panel grid, nearly all the passengers look over the edge to see the other universes (like the cop looking down at the end of the first page of Watchmen, or Thunderbolt doing the same on the last page of issue 3).

Formalism, however, is both a gift and a trap. When stuck in the messy, black-and-white Eddie Campbell world of Issue 4, he comes to realize that the local analogues of his team (and of the Watchmen character) have a reality to them that his day-glo world does not.

“When Peter Cannon arrived here, he thought these people were less than him.

“Smaller. Pete is forty, like Cannon, but Cannon is Hollywood forty and Pete is Northampton forty…

“But Pete is real in a way Cannon isn’t.

“This is real in a way which Cannon isn’t.

“And Cannon realized the horrible truth.

"The feeling he was trying to place earlier?

“Envy.”

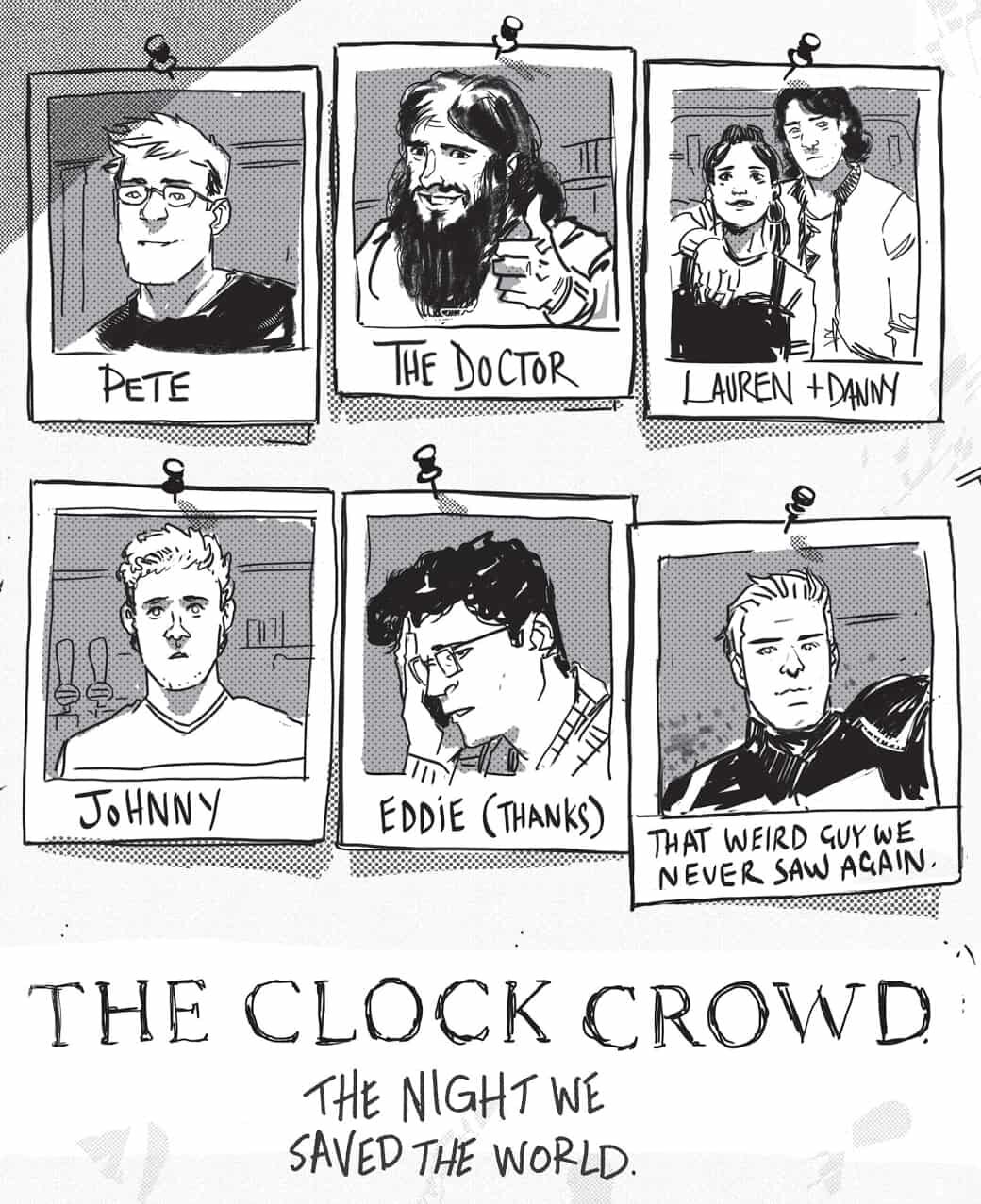

Perhaps it is a function of finding himself in the autobiographical, grounded world of Indie comics, or perhaps it is the simple messiness of both these people’s lives and their world (even the panel borders are rough and ragged, rather than the platonically geometrical shapes of Watchmen. His escape from the Northampton world does not require drawing; instead, Cannon takes photos of all the bar regulars (“The Clock Crowd”), a nod in the direction of the photograph Dr. Manhattan holds on Mars. He arranges them on a wall, like both a comics page and the grid that allowed him and his team to travel in the first place. But, in keeping with the Campbell aesthetic, the six pictures are imperfectly aligned. Cannon calls it “more formalism,” but it is also anti-formalism. Like the hand-drawn panel borders, it is a love letter to the imperfect products of the human hand.

Watchmen redeemed Dr. Manhattan from his nihilistic indifference, and the book as a whole from the temptations of easy cynicism, by doubling down on one of the oldest tropes of Marvel Comics and of mid-twentieth-century televised science fiction: through the recovered recognition of the value of humanity. Dr. Manhattan does not put it in quite these terms; he rediscovers the value of “life,” which he sees as a “thermodynamic miracle.” But that miracle, at least within the cosmology of Watchmen only makes sense when applied specifically to human life. One would be hard-pressed to make an argument about the sheer wonder of a baby hyena born to a male and female who have every reason to hate each other. This reinvestment in humanity is also the reason for the Dan and Laurie plot line, showing the beauty that can result from the romance of two flawed, mostly ordinary human beings.

Peter’s epiphany at the end of issue 4 is more like Dr. Manhattan’s than Dan’s and Laurie’s. It is not about the discovery of his own capacity for love, but about the value and beauty of the most ordinary versions of the people he has met in every alternate universe. It is this understanding that allows him to defeat Thunderbolt, and also prods him back into the world of human contact (his version of the Dan and Laurie plot).

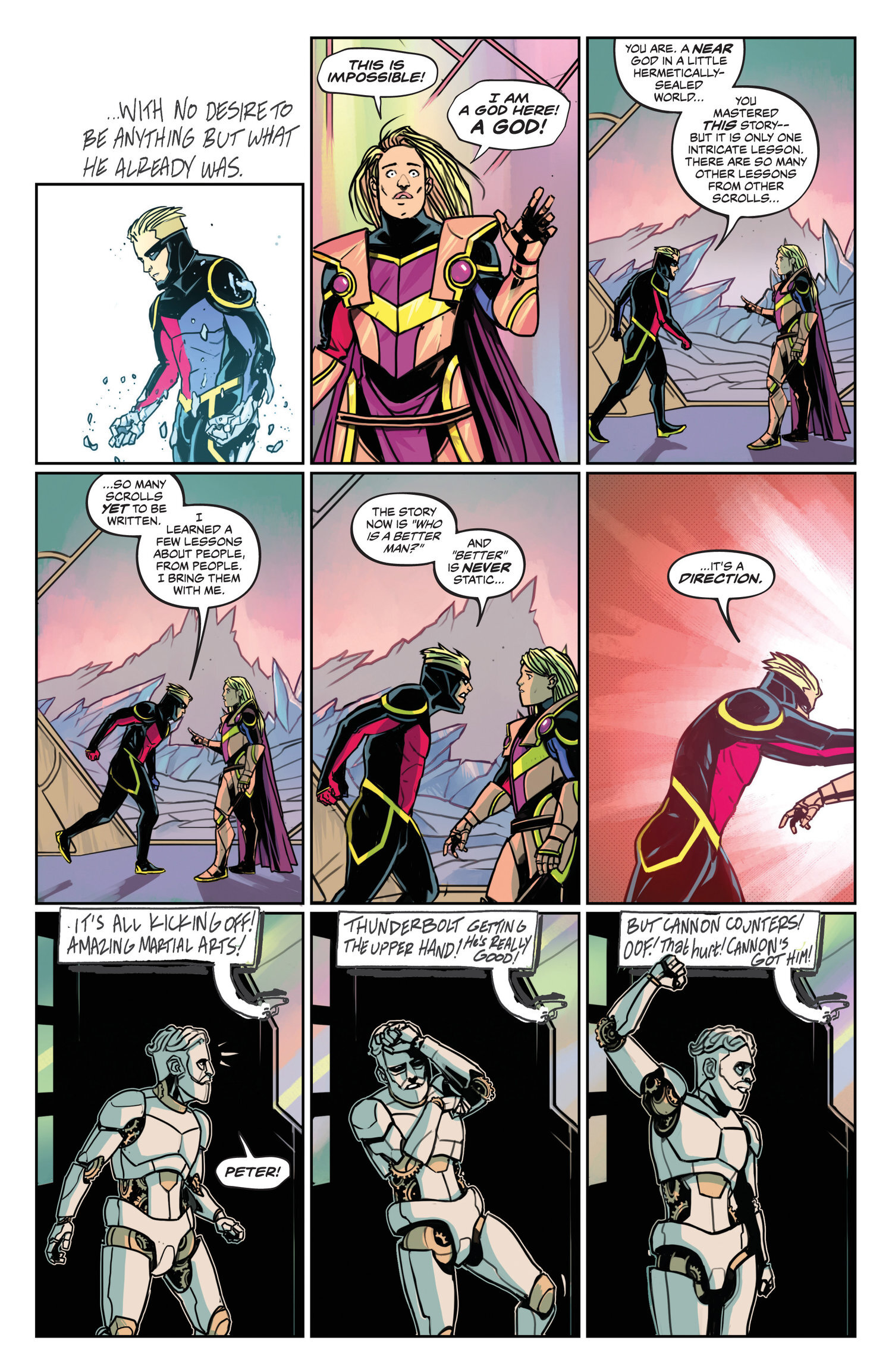

When Peter returns to Thunderbolt’s world, he brings with him an unexpected challenge to the villain’s limited world view: the hand-lettered narrative captions from Issue 4. Every time one of them appears, Thunderbolt is shocked “Wait—! What was that?” The captions allow Peter to resists Thunderbolt’s power, giving him the chance to 1) make a triumphant monologue, like Ozymandias and Thunderbolt, and 2) beat the crap out of his doppelgänger. Thunderbolt is outraged—“I am a god here! A God!”, but Peter points out the flaw:

“You are. A near god in a little, hermetically-sealed world.

"You mastered this story—but it is only one intricate lesson. There are so many other lessons from others scrolls…

“…so many scrolls yet to be written.

“I learned a few lessons about people, from people. I bring them with me.

“The story now is ‘Who is a better man?’

“And ‘better” is never static…

“…it’s a direction.”

It is fitting that, at the point when one Peter Cannon is fighting another, Gillen has brought together all the strands of Peter Cannon lore. The first issue reminds us that Peter gained wisdom from a set of “scrolls” (as part of the original character’s orientalist origins). Now we see what the scrolls have become in Gillen’s hand: another word for comics. At the same time that Gillen reaches far back to Peter Cannon’s origin, he has the hero insult his enemy with a version of a phrase famously uttered by Ozymandias, but now referring to the time that has passed since Watchmen's heyday:

“In the end…this?

“All of this?

“You did it thirty years ago.”

Peter Cannon is literally bashing his evil counterpart not just for his objective crimes (genocide), but for his offense against art: Thunderbolt is stuck in a paradigm that was exciting decades ago, but now that time has passed.

Thus Gillen gets to have his cake and eat it, too: revisiting and revising a classic work in an original and intriguing manner while also declaring that the constant returns to Watchmen have all the forward motion of a broken (doomsday) clock (“better…is a direction.”).

Peter beats Thunderbolt (literally), but he also surrenders to hm, whispering his secret for traveling across the dimensions. Again, he is taking a leaf from Watchmen, but turning it further. Where Ozymandias subverted standard tropes of villainy by setting his genocidal plan in motion 35 minutes before revealing it to his former comrades, Peter decides to transcend the conflict itself. Ozymandias’s entire plan depended on secrecy, leading most of the heroes to remain silent and become accessories after the fact. Peter abandons secrecy altogether.

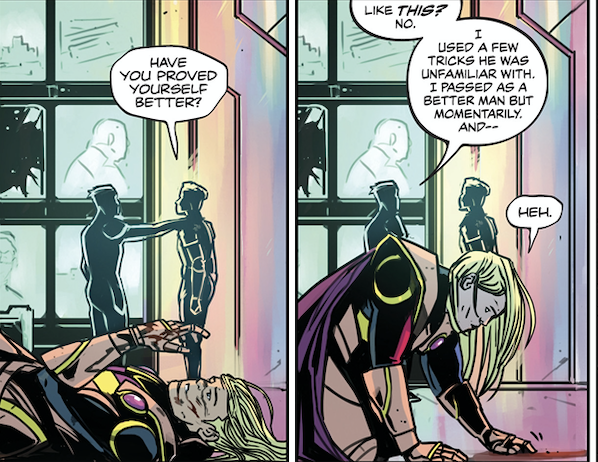

Yet Peter is able to do this because, thanks to his travels, he is now convinced that Thunderbolt will be unable to take advantage of his newfound knowledge. After Thunderbolt’s beating, RoboTabu asks Peter: “Have you proved yourself better?” Peter responds:

“Like this? No.

“I used a few tricks he was unfamiliar with. I passed as a better man but momentarily.”

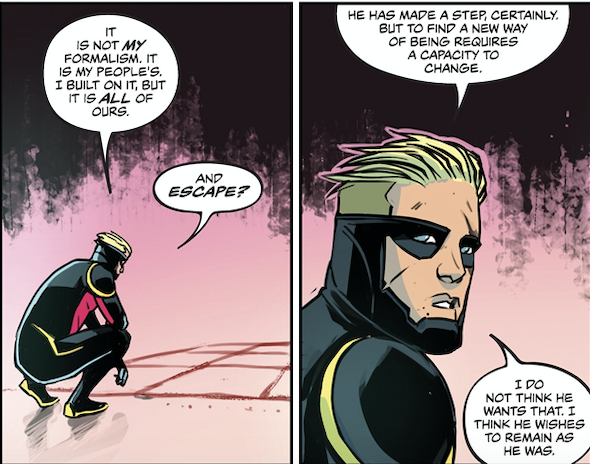

Peter learned to be better from his encounter with the mundane denizens of Issue 4’s world, but he cannot necessarily maintain this state permanently. Unlike Thunderbolt, Peter is someone who embraces change. Peter tells RoboTabu that the formalism he has shared with Thunderbolt is not ‘his,” but rather that of his people:

“I built on it, but it is all of ours.

“And escape?

“He has made a step, certainly. But to find a new way of being requires a capacity to change.

“I do not think he wants that. I think he wishes to remain as he was.”

This formalism, is, of course, the comics form itself. It is not restricted intellectual property, but a common inheritance. What it provides Peter (and where it fails Thunderbolt) is the ability to move into a different world. Like Grant Morrison’s fiction suits, Gillen’s formalism initially looks like a mere device, but is actually the gateway to the particular kinds of enlightenment afforded by good fiction. Where Watchmen parodically confirms the moral panics about comics rotting its readers brains, Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt reasserts the value of fantasy.

And not just any fantasy, but escapism. Escapism is often condemned, but here we see that escapism requires a flexibility of thought that is not available to everyone. When Thunderbolt falls between words and encounters the nine-panel grid, he is momentarily contained in it like the Vitruvian Man, only to be torn into bloody pieces. Watchmen was made possible by the moment when Jon Osterman is shredded atom by atom, only to rebuild himself in a near-perfect form. Peter Cannon ends with an Ozymandias/Dr. Manhattan hybrid dismembered by the power of comics, but without the imagination to put himself back together.

Where Thunderbolt is a strange fusion of the two least human characters in Watchmen (Ozymandias and Dr. Manhattan), Peter Cannon’s trajectory recapitulates that of the Watchmen heroes most defined by their humanity: Dan Dreiberg (Nite-Owl) and Laurie Juspeczyk (the second Silk Spectre). It is Laurie’s story, from her unlikely parentage through her unsatisfied adulthood, that prompts Jon to see beauty once again in life, and it is her budding relationships with the good, imperfect, thoroughly human Dan Dreiberg that stands as a counterpoint to the book’s persistent nightmare images of coupledom (the human-shaped ashes on the wall in Hiroshima and its various permutations on Watchmen’s pages).

Their fumbled first attempts at sex make their later, successful couplings all the more poignant, which is, of course, the point: Dan is no Superman, and his humanity means that he he, unlike Jon, is capable of incapacity. Jon’s lovemaking with Laurie had grown mechanical, and then disturbingly superhuman (he surprises Laurie by splitting himself into three separate bodies and can’t understand why she’s spooked). By contrast, Dan’s superpower is that he is able to be impotent.

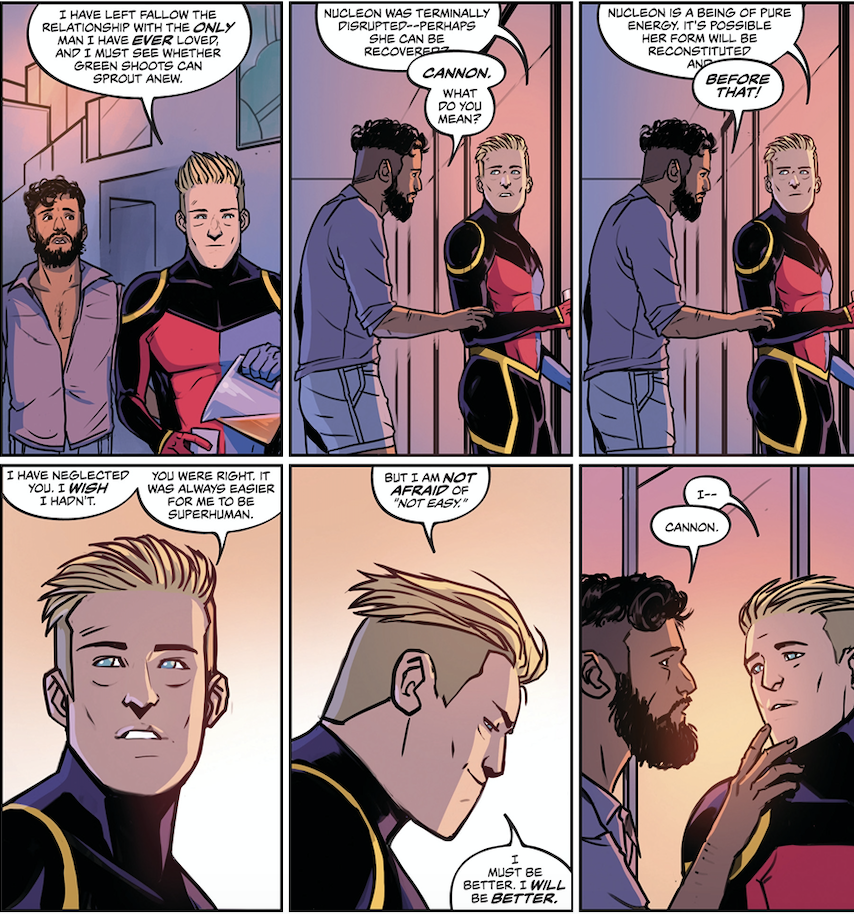

When Peter returns to his home dimension, he brings with him the robotic version of Tabu created by his evil counterpart. Earlier, we were led to understand that this Tabu was so appalled by Thunderbolt that he slit his wrists, and Thunderbolt put his mind into a robotic body whose wrists were invulnerable to harm. Thunderbolt had abandoned his humanity to such an extent that he thought nothing of turning his lover into a metallic android. Peter cannot leave him, because he, unlike Thunderbolt, understands love. This means that when Peter returns, he surprises his own Tabu with a mechanical copy, in an odd inversion of the Watchmen scene with Laurie and the two Jon Ostermans. This time it is not about sex per se (although the fan fiction practically writes itself); it is about love. As Peter confesses to his Tabu:

I have left fallow the relationship with the only man I have ever loved, and I must see whether green shoots can sprout anew.

[…]

I have neglected you. I wish I hadn’t.

You were right. It was always easier for me to be superhuman.

But I am not afraid of ’not easy.’

I must be better. I will be better.

Peter Cannon, the scholar who managed to turn the ancient wisdom of the mysterious scrolls into a force for active good in the world, never stops learning. He learned from the “ordinary” people in Issue 4, and he has learned from the poor example set by Thunderbolt. On, the penultimate page, looking away from Tabu for a moment, he turns his gaze to the reader and, quoting Rorschach, says, “I leave it entirely in your hands.”

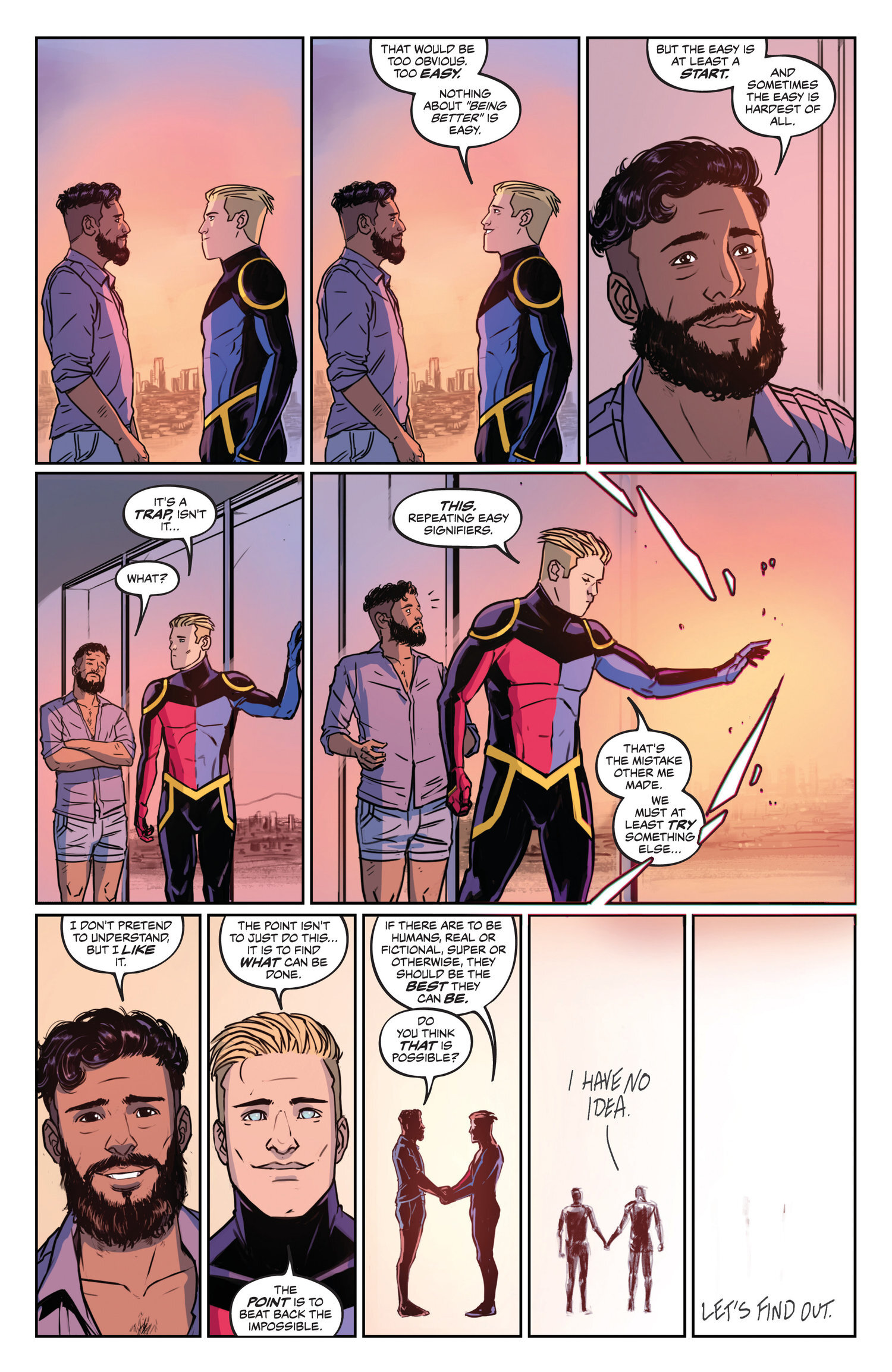

It’s a nice touch, but on the next page, he reveals that this quote from the last line of Watchmen was a fake-out: “That would be too obvious, too easy.”

Had the story ended on the penultimate page, the last thing the reader would take from the updated Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt would be a Watchmen reference, but with a twist: where Watchmen ends with this line in a panel obscuring the character’s face (but focusing on the smiley symbol), Peter Cannon 5 has the title character look directly at the reader, in an echo of Morrison’s “I can see you” (already quoted in a previous issue). This would be clever, but the final page of Peter Cannon 5 suggests that “clever” was all that it would be: an in intertextual in-joke for the smart comics crowd. In other words, it would have been an ending that emphasized what Peter Cannon has been calling “formalism.” [1]

The last page is a rejection of the easy pleasures of structural repetition and parody. Peter tells Tabu:

“It’s a trap, isn’t it?”

“What?”

“This, Repeating easy signifiers.

“That’s the mistake the other me made.

“We must at least try something else."

Tabu, who does not share Peter’s multidimensional perspective, does not understand what Peter is talking about. How could he? Gillen’s Peter Cannon has his own version of Dr. Manhattan’s superpower: comic book vision. [2]. When Peter talks about “repeating signifiers,” he literally breaks the frame surrounding him and Tabu, knocking out the gutter that would have made the central part of the page a three-panel grid. It’s hard to imagine that Peter is rejecting comics themselves, given the connection the series makes between his people’s scrolls and comic books. But breaking the frame asserts the necessity of escaping the trap Watchmen inadvertently set for the complex superhero comics that followed it.

The best thing Watchmen could have done for the industry, the medium, and the superhero genre would not have been the provision of a set of tropes, tricks, and quotes for later creators to play with, nor would it have been the imposition of its dark mood on decades of comics. In the field of memetics initiated by Richard Dawkins, one of the main premises is that memes create culture by encouraging people to copy the instructions, not copy the product. For Peter Cannon, the instructions of Watchmen are to go beyond received cliches and to try something different, and not to just create one’s own version of Watchmen:

“The point isn’t to just do this…it is to find what can be done.

“The point is to beat back the impossible.

“If there are to be humans, real or fictional, super or otherwise, they should be the best they can be.”

Like Jon and Laurie, Peter turns towards human relationships to find meaning in his life. As he and Tabu leave the comics page, they fade into silhouettes (only vaguely reminiscent of the shadow couples in Watchmen), and Peter’s and Tabu’s words change from the comic’s customary lettering to something that looks more like the hand-drawn letters of Issue 4 (the Eddie Campbell issue).

Watchmen’s ending reinforces the book’s emphasis on symmetry and cyclicality, creating the sense that Moore’s and Gibbon’s world is entirely self-contained and self-sufficient (only Dr. Manhattan manages to escape it, and it is his departure that ensures that this world will now be immune to a blue-tinted deus ex Manhattan). Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt points the way out of the story, disrupting panel borders and sending its protagonists to walk away from visual representation entirely. Gillen’s ending is radical in its sentimental simplicity: Peter Cannon and Tabu go off to live happily ever after.

Note

[1] In his commentary on Issue 5, Gillen writes:

“Of course, this segues to the Watchmen nod in the final panel of the page. I suspect if you were to make a bet on what my final panel would be, it’d be that line.

“Which of course means we can’t do it, as that would be defeating the whole purpose of this endeavour.”

[2] In an issue of Captain Marvel, Peter David reveals that eternal sidekick Rich Jones has a power that goes beyond the title character’s “cosmic awareness.” Rick has “comic awareness,” which means he knows when a series is about to get canceled.

Comments (1)

Anders Davenport 6 months ago · 0 Likes

I didn’t even know about this series, but it looks fantastic. I’ll be picking this up once it’s collected as a trade, thanks for spreading the word.

“[2] In an issue of Captain Marvel, Peter David reveals that eternal sidekick Rich Jones has a power that goes beyond the title character’s “cosmic awareness.” Rick has “comic awareness,” which means he knows when a series is about to get canceled.”

I’m always happy to find a fellow Peter David fan. I read his Captain Marvel run, and while I remember the overall “cosmic awareness” part of the character, I must have forgotten the “comic awareness” pun you mention. That’s very funny, and very Peter David. Bravo for the reference!