Vigilantes and Bystanders

[SPOILER WARNING for a thirty-three year old story]

Watchmen was not the first comic to call into question the vigilantism at the heart of the superhero, nor was it the first to imagine a world in which superheroes are outlawed. [1] Where Watchmen stands out is in placing superhero vigilantism on a continuum of citizens' action and inaction. Four figures are crucial here: Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, Adran Veidt, and a group of ordinary people on a New York city street corner.

As the most violent and unrepentant masked hero, Rorschach embodies a particularly harsh vigilante justice. But as he tells his life story to the prison psychiatrist, he locates the familiar comics trope of the "secret origin" in the story of Kitty Genovese, whose murder in a New York City courtyard was allegedly witnessed by dozens of bystanders who did nothing to stop it. [2]

YES, LADIES, HE’S SINGLE!

This incident, which became emblematic of urban breakdown in the 1960s, is personally linked to Rorschach (his face mask was made from the dress Genovese had left at the cleaner's before her death). Rorschach will not be a bystander; he will take action. His transformation into a quasi-sociopathic crusader for justice is complete when he subsequently discovers that a kidnapped little girl has been butchered and fed to guard dogs. Setting the girl's murderer on fire, he realizes that there is no meaning in the universe, no God, and no justice. And this means it is imperative for individual humans to provide justice where they can.

By contrast, the most powerful character in the book, Dr. Manhattan, has become so distant from humanity that, as he says regarding his earlier exploits, "The morality of my actions escapes me." Theoretically, he could prevent World War III with the blink of an eye, but he has to be convinced to that it's worth the bother.

JON OSTERMAN REALIZING HE’S IN THE WRONG GENRE

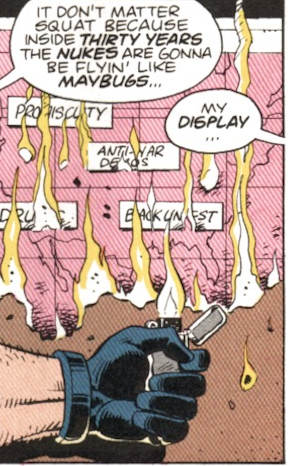

The architect of Watchmen's apocalyptic scenario is Adrian Veidt, whose eyes had long ago been opened to the world's impending doom by the Comedian. The Comedian, ridiculing a proposal by aging has-been heroes to band together to combat such "crimes"as "anti-war demos," "promiscuity," and "black unrest," warns Veidt that, when the missiles fly, he'll be "the smartest man on the cinder." Veidt wants to replace the futile, never-ending street-level intervention of vigilantes such as Rorschach with a global strategy to ensure world peace. Inspired by his personal hero, Alexander the Great, who "solved" the Gordian Knot by slicing through it rather than unraveling it, Veidt concocts a rather baroque plan to bring the world's warring parties together in the face of a presumed extradimensional threat (in actuality created by Veidt himself), at the cost of the lives of a mere few thousand New Yorkers.

HOW DOES A SUPERHERO FIGHT PROMISCUITY? BY PUNCHING IT?

For Veidt to take his murderous action, he needs merely press a button. But the readers, who do not initially understand what that button signifies, are forced by the narrative to experience this human sacrifice as a very real loss. Throughout most of the book, we have been following the interactions of several ordinary New Yorkers at a midtown street corner. The payoff comes when they are all killed by Veidt's scheme to bring about a worldwide utopia. Moreover, the precise moment at which these men and women are killed occurs when nearly every ordinary character we have been following is attempting to stop a woman from beating up her ex-lover. This is Watchmen's anti-Kitty Genovese moment: a group of New Yorkers refusing to stand by while a crime is being committed. And this is when Veidt kills them.

Notes

[1] This post is based on one of my contributions to the forthcoming Oxford History of the Novel in English Volume 8: American Fiction since 1940, edited by Cyrus R. K. Patell and Deborah Lindsay Williams.

[2] The original reporting on the Kitty Genovese murder, as well as the conclusions drawn about the “bystander effect,” have been called into question in recent years. See Marcia M. Gallo “No One Helped: Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.