Drugs Are Bad, m'kay?

"Relevant" superhero comics also tried to address the question of illegal drugs. This proved to be a problem, because the Comics Code would not allow any depiction of drug use, even for the purposes of condemning it. Stan Lee and Gil Kane insisted on publishing a Spider-Man story involving a pill-popping Harry Osborne (Amazing Spider-Man 96-98, May-July 1971), while O'Neil and Adams revealed that Roy Harper who fought at Green Arrow's side as Speedy (!), was a heroin addict in two Very Special Issues called "Snowbirds Don't Fly!" (Green Lantern/Green Arrow 85-86, August-November 1971). These issues are celebrated for forcing the Comics Code Authority to relax a number of its policies (thereby ushering in an era of innovation in the 1970s), but as stories, they are more instructive in their failings. Both drug abuse and racism make for poor super-villains. What is a superhero supposed to do about heroin addiction--punch it in the face and throw it in jail?

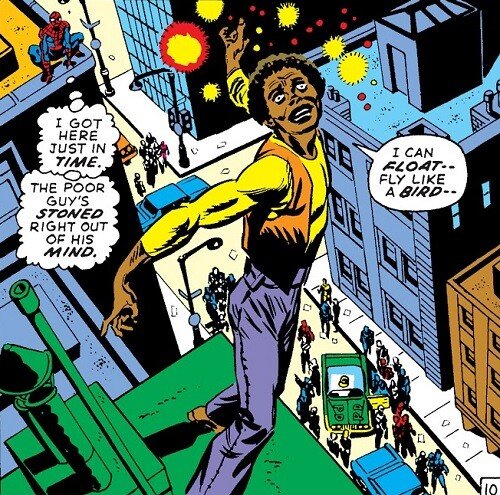

You will believe a man can fly

The moralizing of superhero anti-drug stories is intense, but it is par the course: mass media messages about the dangers of drugs in the 1960s and 1970s rarely left room for nuance. But the problem goes deeper than that. When it comes to drugs, the entire superhero genre is on very shaky grounds, since so many superheroes got their powers from...drugs. Ralph Dibney drinks an exotic fruit extract called Gingold to gain the flexibility of the Elastic Man. The final part of Steve Rogers' transformation into Captain America involved drinking a super-soldier serum, and another drug in the 1970s inadvertently enhances his super strength. With the benefit of hindsight, the most egregious example is DC's Hourman. Created in 1943 by Ken Fitch and Bernard Baily, Hourman was the secret identity of chemist Rex Tyler, who invented a pill called "Miraclo" that gave him super strength and speed for exactly one hour. Decades later, it was revealed that both he and his son, Rick (the second Hourman) struggled with Miraclo addition. The superhero junkie would receive his apotheosis when The Sentry, created by Paul Jenkins, Jae Lee, and Rick Veitch in 2000, was revealed not to be just a naive boy who used a scientist's secret formula, but a drug-seeking schizophrenic who wanted to get "higher than a thousand kites" (Sentry 8, 2006).

By the time the Sentry's origin was revealed, the superhero comics industry had reached a point where engaging in this kind of parodic deconstruction of the genre's tropes was already old hat. For the most part, drugs and addiction were simply woven into characters' narrative arcs as an ordinary fact of people's lives rather than an example of a metaphysical threat: Carol Danvers' and Tony Stark's alcoholism, for example, may have initially been depicted in a melodramatic fashion, but they ultimately became familiar character traits (at least in Stark's case; Danvers' personal history is too complicated to go into). Roy Haper's struggles with addiction were treated with more subtlety once they were an element of his past history rather than his present struggle. [1]

Note

[1] At least if we exclude J.T. Krul's and Geraldo Borge's 2010 miniseries Justice League: The Rise of Arsenal, which most readers are only too happy to do.

Next: We Are the World (of DC and Marvel)