There Goes the Neighborhood

Chapter 4

Russia's Alien Nations:

Agents, Spies, and Extraterrestrials

There Goes the Neighborhood

Losing borders is like losing skin. It's not just that the body (politic) is obliged to change its shape, but that a reliable surface layer of protection has vanished. Open, porous, thin-skinned, the nation's collective body is subject to penetration, infiltration, and contamination.

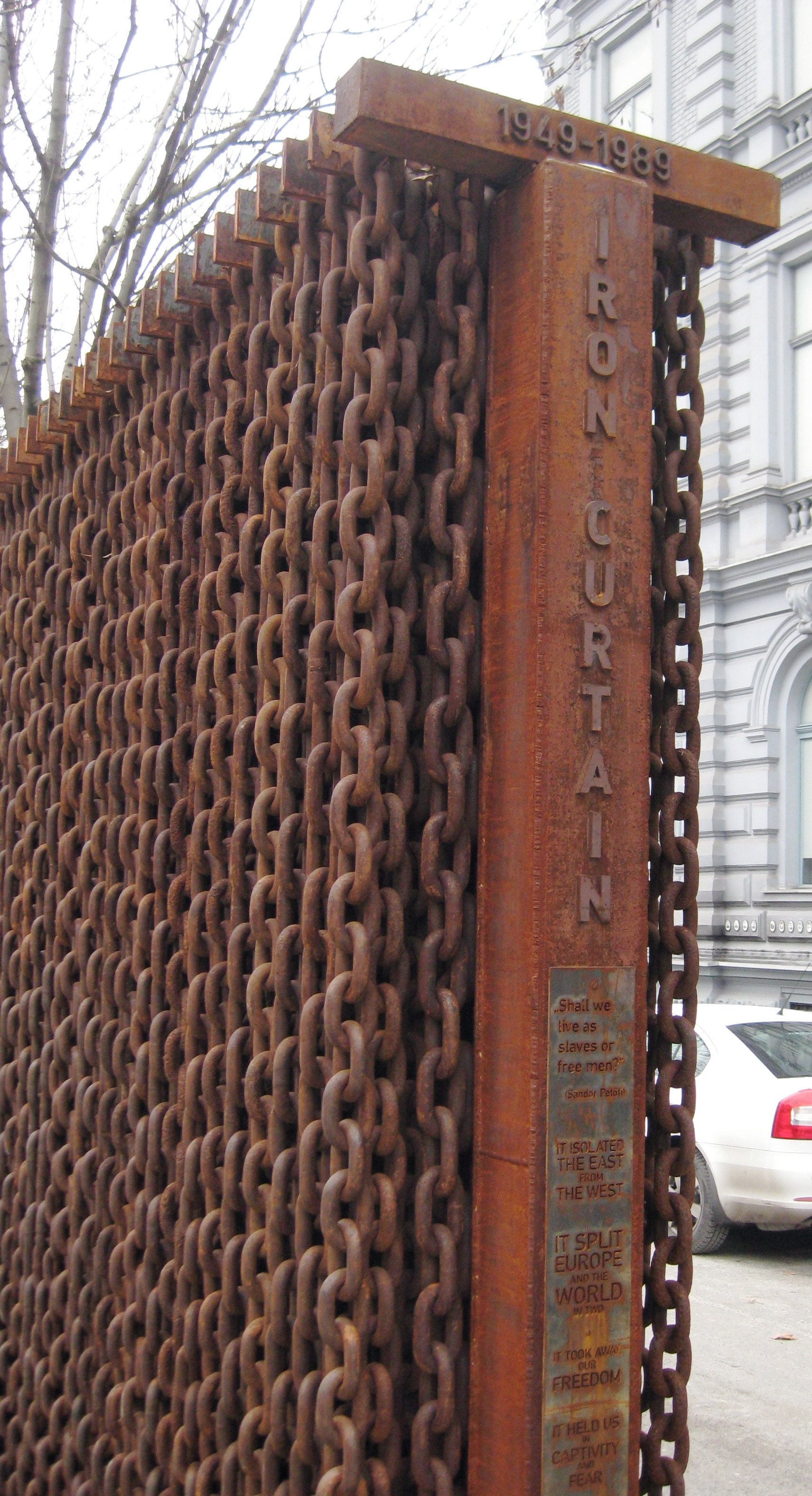

The last years of the Soviet Union and the early years of the Russian Federation launched a period of refreshing, even shocking cosmopolitanism. Borders opened (or fell), international travel became, if not commonplace, then eminently thinkable, and foreign investment was officially encouraged (although the legal and regulatory environment turned such encouragement into a mixed message). The iron curtain, already a hackneyed metaphor, describing the entire Soviet bloc, gave way to the transparent screen: there was no longer any need to peak behind it.

The obligatory Iron Curtain. You’re welcome.

This is not to say that the Soviet Union was an autarky, or that, to the extent that it was sealed off from potential foreign subversion the USSR's relative isolation was effortless. In Stalin's time, the emphasis on vigilance was code for paranoia, as the NKVD and informers ferreted out "spies" and "wreckers" (saboteurs) on the flimsiest of evidence. World War II not only wrecked whatever sense of national security the Soviets may have had, it also brought the country close to total ruination. During the Cold War, vigilance was less a matter of hunting for spies than it was of countering seductive foreign influences: jazz, rock, the counterculture, and commercialism, not to mention the more straightforward ideological threat posed by democratic and capitalist models. Vigilance was supposed to be a kind of self-discipline, but in the Brezhnev Era, it expressed itself more in terms of surveillance (Komsomol organizers, teachers, bosses) and a growing gap between the generations. Policing foreign input could not curtail citizens' desire for it, in any of its myriad forms; to the contrary, efforts at control only made the desire stronger.[1]

The removal of restrictions on travel and the abolition of censorship on the cusp of the Soviet collapse inevitably brought on a flood of Western imports, both physical and cultural. Was this a long-awaited opening to the outer world, leading to the moment when Russia will be invited to join the global community with open arms? Or was it all a pretext for the cultural, political, and economic colonization of the former Soviet Union by the aggressive forces of a capitalism that, in the absence of a communist alternative, could assume eternal hegemony? This chapter looks at narratives and tropes of a vulnerable Russia suffering from invasions and infiltrations of all kinds, from foreign institutions masking their malign intentions in the guise of humanitarian and developmental assistance to unscrupulous foreign businesspeople, from foreign spies to domestic forces that have compromised themselves as foreign agents, and even the occasional extraterrestrial invader.

We start with the influx of foreigners from the West, seeking investment opportunities, chances to engage in the construction of civil society, evangelize the locals, and cultural and education exchange. In English, these visitors are generally called "expats;" the people who fled to Russia due to post-Soviet civil conflict and economic depredation were, at best, called refugees or migrants. It is the latter category that more often (but not exclusively) sparked a common colloquial lament: "Понаехали!" The word means "arriving in large numbers," or "overrunning," but the context is closer to the English phrase "There goes the neighborhood." Particularly in the big cities, the appearance of newcomers, often with a limited command of the Russian language and an appearance that is euphemistically referred to as "non-European" or "non-Slavic," made some inhabitants long for a time when immigrating or even simply changing domicile was a matter of strict regulation.

The Westerners who arrived were generally more welcome, but still subject to suspicion. What possible reason could they have to come all this way? Greed, exploitation, and indoctrination were all distinct possibilities. Philanthropy and charity work each sparked skepticism. But what is particularly telling is how certain famous Westerners and foreign entities whose activities were, on the whole, greeted warmly in the 1990s have been reinterpreted as part of a plot to destroy Russian culture, undermine Russian values, and render the country forever dependent on Western Europe and the United States. To understand, we need to look no further than one of the most famous investors and philanthropists in the post-Cold War world: George Soros.

Note

[1] In Flowers through Concrete, Juliane Furst demonstrates that the 1970s Soviet publications devoted to condemning hippies actually served as something of an instruction manual for Soviet would-be members of the counterculture.

Next: Hooked on Grants