Move Fast, Break Things

The use of mind control is a glaring moral failing, but it also highlights the limitations of the superhero genre. What is left for superheroes to do if there is no one else to fight? Since the Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-1951), the Man of Steel's job has been described as a "never-ending battle" (initially for "truth and justice," but by the time the show moved to television (1952-1958), it was "truth, justice, and the American way"); this is a phrase that can be applied to the superhero genre write large. Superhero stories are generally serialized; there can be no end to the battle not just because crime continues in the "real world," but because the corporate imperative to maximize profit and the public appetite for more stories makes true endings inimical to the storyworld. In attempting to solve their world's problem, the Squadron becomes the problem, not just because they are curtailing freedoms, but because the rules of the genre require that they have someone to fight.

Resorting to brainwashing also highlights the basic problem with both superheroes and this particular attempt to change the world: the Squadron is either unwilling to, or (more likely) incapable of reflecting on their own ideology. As heroes, the fought "crime," upheld the status quo, and therefore were subject to being mislead when their leaders proved corrupt. As utopian dreamers, they have not bothered to develop a theory or working model of society. They act like technocrats, and in the absence of anyone above them to provide guidance, they can only see the most obvious problems. This is one of the few points where their approach converges with that of Watchmen's utopian schemer, Adrian Veidt. Veidt prides himself in following Alexander the Great's approach to the Gordian knot: it is to be simply severed rather than unraveled. The metaphor has its appeal, but it carries with it a fundamental denial of complexity. Veidt should be smart enough to know better; the Squadron, despite the presence of scientific geniuses in their ranks, does not have the wherewithal to realize that they are leaving basic philosophical questions unasked and unanswered.

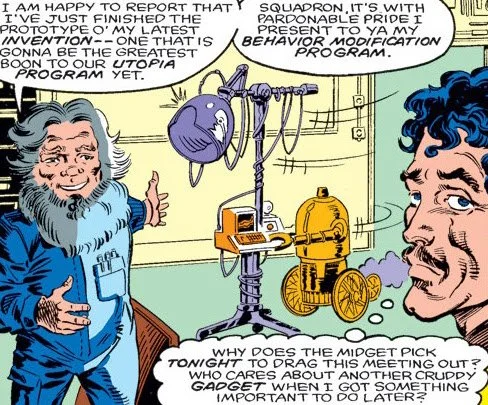

Poor Tom Thumb! He creates a totalitarian mind control device, and what is the thanks he gets from his teammate? A bigoted slur

The fundamental cluelessness of the Squadron Supreme makes them frustrating, but it an integral part in making their miniseries work, just as the book's indebtedness to continuity, while making Squadron Supreme a difficult reading experience for the uninitiated, allows it to stake a claim that Watchmen cannot. Though both books started as twelve-issue series, Watchmen deliberately departs from the traditions of serial superhero storytelling. As ambiguous as its final panel is, the book nevertheless comes to a true conclusion. Watchmen deconstructs the serial superhero comic in a format that lends itself to a beginning, middle, and end. Squadron Supreme, though telling a more or less complete story, has to address the conventions of the superhero as part of Marvel's neverending narrative flow; even the book's sequel, whose title (The Death of a Universe) promises finality still manages not to provide a true ending to the characters' adventures.

The Squadron may have started as a parody of the Justice League, but it morphed into an ongoing satire of two key elements of the superhero genre: the hero's lack of engagement with the systemic questions that frame their adventures, and the expectation that the hero will always win. The Squadron Supreme exists to lose, and to lose again and again. Were it not for the seriality of their adventures, any given Squadron Supreme story could function as the superhero equivalent of tragedy: not only does the Squadron collectively suffer from a tragic flaw (their political and philosophical naivete), but by the stories' end, the body count has reached near-Hamlet levels. The Squadron Supreme miniseries abruptly tries to change its tone in the very last panel, moving from the morgue to the delivery room for the birth of Arcanna's baby, but the shift is too little, too late. There is little room to assert that Squadron Supreme has a happy ending, or, for that matter, that the team itself has any prospect of an optimistic conclusion to any subsequent adventures. If Sophocles, instead of writing the plays that survived to our day, had written a series of Oedipus dramas that each somehow ended with the title character once again putting out his own eyes, the result would have prefigured the saga of the Squadron Supreme.

Next: Second(ary) World Problems