Plot Cancer

If Squadron Supreme suffers in comparison to Watchmen, it is at least in part a question of each work's relationship to its own time. And this is even while making allowances for Gruenwald's preoccupation with continuity as a legitimate artistic choice. The real problem is that, despite appearing within a year of each other, they read as if their production were separated by decades. Watchmen set the standard for superhero stories going forward; for good or ill, it changed the verbal, visual, and thematic vocabulary of the genre. Squadron Supreme, by contrast, is a perfect example of how comics were made before Alan Moore's influence. Thought balloons are everywhere; the main characters tend to explain their motivations out loud, the art is unexceptional, and the minor characters are written and drawn as if they are just waiting around for the protagonists to interact with them.

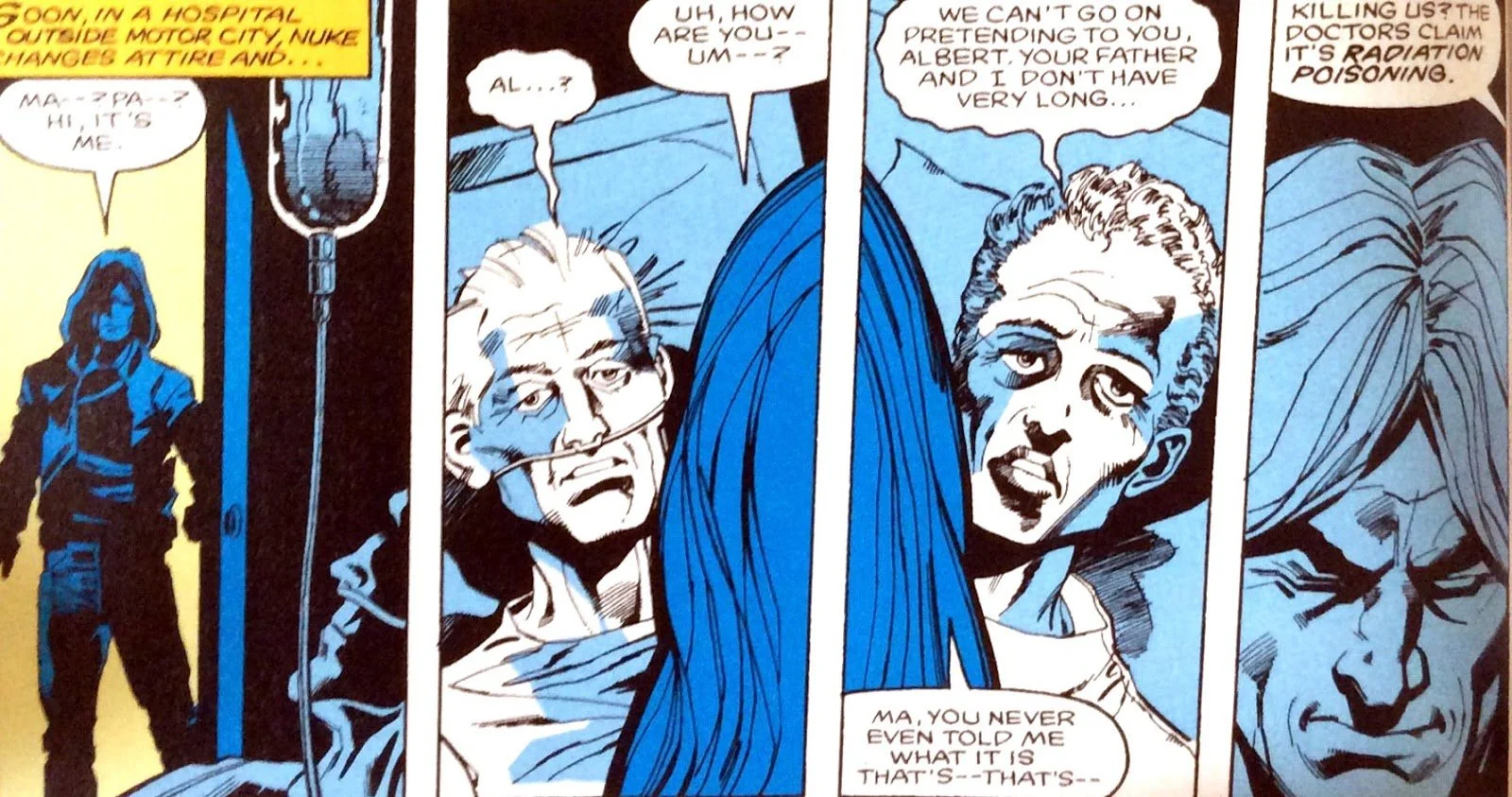

When the young hero Nuke (an analogue to DC's Firestorm) is worried about his parents, who are dying of cancer caused by exposure to his radiation, he visits them in the hospital. Dressed in identical robes and sporting near-identical short hair, his mother and father actually share a room there. As is typical in mass culture at their time, they just have "cancer" (no organ is specified, no stage is named), and when Nuke asks them about their status, his mother answers, "They want us to continue chemotherapy for a while longer, son." In other words, they function as one patient in the hospital, with one chemotherapy protocol. My point is not that this is bad medical care; nobody was reading Squadron Supreme to learn about oncology. Rather, their disease, suffering, and hospitalization only exist to the extent that they have an impact on Nuke.

Nuke's parents' cancer is not without value to the story. It is a step in the direction of "real world" problems being taken up by superhero comics, starting with the basic acknowledgment that a character whose powers are based entirely on radiation might be a danger to those around him. Their illness also raises a question that haunts the genre: if the world is populated by supergeniuses, why haven't their discoveries led to significant technological and social change? Why not use those superbrains to cure cancer? Marvel brought up the same question just three years earlier in Jim Starlin's The Death of Captain Marvel, when Rick Jones challenges Reed Richards, Hank Pym, Hank McCory and other superhero scientist to cure Mar-Vell of the disease that is killing him. In Squadron Supreme, Nuke begs resident genius Tom Thumb to work a similar miracle, setting him on a convoluted path involving an intelligent female super-ape who falls in love with him, a tyrant from the far future, and Tom's own (ironic!) death from yet another case of unspecified "cancer." The race for a cure is a dead-end; the miracle elixir Tom gets from the futuristic tyrant won't work in our time, and Nuke actually precedes Tom in death: his guilt over his parents' demise send him off the deep end, prompting a fight with his teammate Dr. Spectrum, who accidentally kills him.

As this brief summary of only a minor plot thread shows, Squadron Supreme leaves a high body count: Tom Thumb, Nuke, Nuke's parents, Golden Archer, Pinball, Nighthawk, Foxfire, Blue Eagle, Lamprey, Power Princess's husband, and Hyperion's evil counterpart from the Squadron Supreme. In addition, Ape X is comatose, and Thermite is in critical condition with a "10 percent chance of recovery." The book ends on optimistic note (Arcanna gives birth to a son), though the 1989 follow-up, Squadron Supreme: Death of A Universe dispenses with Inertia, Professor Imam, and the Overmind (don't ask), even if the book failed to deliver on the total annihilation promised by its title. The world of the Squadron Supreme kills off characters with a What If? level zeal (though at least their deaths have consequences as part of an ongoing set of stories).

No, no, no! The parents are supposed to die during the origin!

With all these caveats and complaints, and given how many other examples there are of superheroes trying to solve the world's problems, what makes Squadron Supreme worth considering? As is often the case with interesting comics that have never managed to rise to the status of universal acclaim, the flaws are as revealing as the strengths. Where Watchmen, despite its apocalyptic sensibility, charts a future for superhero comics though an unusually complex relationship to genre (simultaneously digging deeper into superhero tropes while also looking beyond them), Squadron Supreme is an exploration of the superhero as a dead end. The superheroes themselves are at a loss, turning to their utopian project out of desperation; the storytelling, which does not push the conventions of mainstream comics forward even an inch, feels particularly leaden in the context of a plot about breaking with the status quo, while at this point in publishing history, Marvel Comics, with the exception of X-Men, Thor, and Daredevil, has shown precious few signs of inspiration or innovation since Jim Shooter drove out most of the company's best talent by the end of the Seventies. The format of Squadron Supreme, a twelve-issue "maxi-series" was new for its time, but even as it experimented with publishing models throughout the Eighties, Marvel was largely conventional when it came to content. The Squadron Supreme do not just fail to save their planet; they fail to show that there is much life left in the superhero concept.

Next: A Magnificent Failure