This Is a Job for....Procedural Democracy?

The superhero is, among other things, a fantasy about noble vigilantes who can fight crime more effectively than the representatives of our political and judicial institutions (see Chapter 3). While they are normally constrained by a generic conservatism that requires the maintenance of the status quo, mainstream superhero comics have occasionally taken the opportunity to imagine a hero who aspires to make systemic change, either from within (by running for office) or from above (by taking over entirely). Given how obsessed American culture is with celebrity, and the occasional successful celebrity candidates for office, a superhero president makes a certain amount of sense.

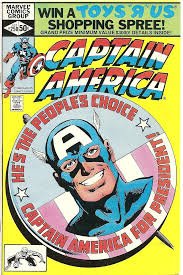

Especially after the election of former movie star Ronald Reagan. For Captain America's 250th issue, which came out four months before Reagan's victory, a team of four writers (Roger Stern, Don Perlin, Roger McKenzie, and Jim Shooter), working with artists John Byrne and Ed Hannigan, confronted the hero with a growing popular demand that he run for president. After giving it several pages of thought, Cap unsurprisingly declined to run. On the face of it, it was a very Silver Age-style idea dragged into a more sophisticated time (Captain America's identity was still a secret; how was he supposed to campaign for president?). But the explanation he gives on the final pages is a surprisingly apt summation of the problem his presidency would pose for superhero comics:

[The president] must be ready to negotiate--to compromise--24 hours a day to preserve the republic at all costs.

I understand this... I appreciate this...and I realize I need to work within such a framework. By the same token...

...I have worked and fought all my life for the growth and advancement of the American dream, and I believe that my duty to the dream would severely limit any abilities I might have to preserve the reality.

We must all live in the real world.... and sometimes that world can be pretty grim. But it is the dream...the hope...that makes the reality worth living.

The writers pose the question in terms of political process vs. idealism, but they might as well be talking about the real world vs the superhero genre. The superhero acts in a realm that rarely requires subtlety, compromise, or the dreary back-and-forth of proceduralism. Fittingly for a Captain America comic, this problem is exacerbated by the peculiarities of the American system. In a parliamentary system that grants executive power to a prime minister and ceremonial authority to a president, electing Captain America might be more feasible. But then we wouldn't be talking about Captain America or the "American dream." Still, superheroes are more compatible. with heads of states (or even figureheads) than they are with actual chief executives. [1]

Really, what could go wrong?

Captain America is not alone in flirting with the presidency; a Silver Age story has Jimmy Olsen dreaming that his pal has ascended to the oval office, while the Armageddon 2000 crossover included a possible future with the Man of Steel as president. In Final Crisis, Grant Morrison introduced DC readers to Earth 23, where a black man named Calvin Ellis is both President and secretly Superman. This "President Superman" would subsequently be brought back on multiple occasions. Mainstream DC continuity could not make room for Superman as president, but for years, Lex Luthor held that office in the DC Universe.

The fantasy of a superhero attaining the highest office in the land by means of free and fair elections is the desire for a perfect synthesis of vigilante romanticism and democratic proceduralism. In this scenario, we can keep our democratic institutions while secure in the knowledge that the man (and, let's face it, we're usually talking about a man here) at the top is not just competent and honest, but a paragon of humanity. It is the ideal fusion of the head of government, head of state, and man of steel. It is also unsustainable, not just because of hard-bitten cynicism about how politics actually work, but because the heroes who take on the country's leadership are not designed to bear such a burden with any kind of plausibility. [2]

But why should we expect a superhero to be content with the slow, demeaning process of a presidential campaign? The average superhero's career is premised on the desire to work outside the system, to cut corners, and to mete justice more effectively that any legal executive power might manage. Seizing power is a classic supervillain move; villains tend either to rob banks, murder indiscriminately, or try to take over the city/country/world, and it is usually up to the hero to stop them. Yet there is an easy homology between fighting crime as a vigilante and taking control of the government in order to improve people's lives. [Find name] draws a parallel between the detective story ("Let's solve a crime") and utopia ("Let's solve all crime"), one that easily maps onto the superhero ("Let's stop a criminal" and "Let's stop all criminals"). Beyond the question of crime, the homology is based on a disdain for institutions in the name of the very ideals that the institutions are supposed to uphold: justice (by circumventing the niceties of the justice system) and peace (by beating up those who threaten it). When the ethos of vigilantism is expanded to the scale of government, it could justify the seizure of power by well-meaning superheroes (it can also justify fascism, but that's for a later chapter).

The superhero government takeover has become such a familiar trope that it has even migrated from its comics origins to other media: the "Justice Lords" scenario on the Justice League cartoon in which a version of the Justice League take power on a parallel earth after the death of the Flash ("A Better World," Episodes 37-38, November 1, 2003). The 2013 video game Injustice: Gods Among Us, which has Superman and his allies take over the world after the Joker kills Lois Lane, launched an entire franchise (more games, multiple volumes of comics, and an animated adaptation). Compelling as these stories may be, they are based on an even more common trope: the superhero who goes bad. Though in each case, the heroes who take over claim that they are making the world a better place, the impetus is personal loss. It's a scenario that makes the heroes briefly sympathetic, but it also represents a deliberate break from one of the most common superhero origin stories. Bruce Wayne becomes Batman because his parents were killed; Peter Parker learns the lesson of great responsibility from his inadvertent role in his uncle's death. Even the original Ant-Man (Hank Pym) is motivated by the death of his first wife. With the exception of the Punisher, who started out as a response to the eye-for-an-eye ethos of the Dirty Harry movies, revenge is rarely the right path for the superhero.

Of more interest, than, are those moments when the hero or heroes make the conscious, relatively unemotional decision to solve the world's problems by taking the reins of government. This has happened on numerous occasions, but always either in a parallel world or timeline (Squadron Supreme), in a small, self-contained superhero universe (The Authority, Miracleman), or in a story destined to be reconned (Thor: The Reigning, as well as The Authority). Just as the first volume of Marvel's What If? series served primarily to remind readers that the main continuity was the best of all possible worlds, these alternate world explore forbidden scenarios as cautionary tales. It would be unrealistic to expect corporate comics to tell the story of a superhero takeover that was successful and benign; not only would this be politically unpalatable to anyone who believes in procedural democracy, as well as an implicit endorsement of fascism (no matter what the explicit policies of the superhero leaders happened to be), but it would also fall into the trap that awaits most utopias: as a plot, it is a dead end. Utopias are generally inhospitable to the development of compelling plots, since all major problems have been solved. All that's left for the reader to do is to learn about the utopian world, but the result is less like a novel and more like a tour guide. Gaiman's and Buckingham's follow-up to Alan Moore's Miracleman stories recognizes this limitation while pushing against its boundaries. At the end of Moore's run, the title character and a group of allies have created a paradise on earth after one of their former comrades tortured and murdered nearly the entire population of London. Gaiman and Buckingham were taking their time (decades, in fact, due to the problems surrounding the book's publication) to explore this new world in a series of one-short stories. [3] The world may be more or less perfect, but the adaptation of the individuals who live in it is still idiosyncratic, contingent, and not always personally satisfying. [4]

In the mid-1980s, both DC and Marvel published 12-issues limited series that featured superheroes crossing the lines in order to save the world. One of them, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen, whose plot hinged upon a brilliant former hero's decision to end the Cold War through complex subterfuge, is widely recognized as a classic in the world of graphic novels. The other, Squadron Supreme, written by Mark Gruenwald with pencils by Bob Hall, Paul Ryan, and John Buscema, is best remembered for the fact that, at Gruenwald's request, the first printing of the collected edition of the series used ink mixed with his own ashes after his premature demise.

Notes

[1] Marvel has repeatedly returned to the idea of a President Captain America, but always in stories or settings that are safely outside of mainstream continuity. Two different issues of What If? explore this possibility (What If vol 1, 26, April 1981 and What If, vol 2, 28), and not long before the Ultimate Marvel Universe was destroyed, Captain America became president of a fractured nation which he sought to unify.

[2] Exceptions are made for alternate universes and timelines, of course, but also for futures that may or may not come to pass. Marvel has repeatedly returned to the idea that Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel) will one day grow up to be president. Kamala's presidency does not strain the superhero framework as much as Superman's or Captain America's (even taking into account that she is a brown Muslim Inhuman mutant woman with weird powers), because Kamala is still a teenager. Her future presidency is a statement about her potential rather than her actuality, and is also consistent with the overall optimism of Ms. Marvel's own comics. In addition, the progressive character of Kamala's successful presidential bid (again, brown, female, Muslim, mutant, Inhuman) counterbalances the populist and even fascist overtones of electing a superhero.

[3] The rights to the character now best known as MIracleman are a saga until itself. The character was created by Mick Anglo after his British publisher lost the rights to reprint Fawcett's Captain Marvel (who is now best known as "Shazam"). To replace the Marvel family, Anglo barely changed them: Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel, Jr.l became Marvelman and Young Marvelman. In the 1980s, Dez Skinn hired Alan Moore to revive the character for his new Warrior anthology. Moore completely revamped the character, turning it into the first of many deconstructions of the superhero archetype. When the stories were reprinted in the United States by Eclipse Comics, the name was changed to "Miracleman" to avoid lawsuits from Marvel Comics. Moore completed the story he planned and turned the book over to Gaiman. Gaiman and Buckingham produced eight issues of Miracleman from 1990-1991. Moore also gave Gaiman the rights when Eclipse collapse. However, Todd McFarlane purchased Eclipse's assets and claimed ownership to Miracleman. Lawsuits ensued, until it was discovered that Anglo was still alive and owned the rights. Marvel purchased the license from him 2009 and began reprinting the series, but only started publishing new material by Gaiman and Buckingham in 2022. Thus the gap between their first run on the book and its revival was 31 years. Subsequently, the allegations that Gaiman assaulted several women put an end to the Miracleman revival.

[4] At the same time, they are also setting up a major challenge to the new status quo that will probable lead to its downfall.

Next: Earth's Mightiest Punching Bags