Kinder, Gentler Kidnapping

According to Ukrainian sources, nearly 20,000 children have been forcibly removed from Ukraine to Russia since the 2022 invasion, a practice that turns out to have begun with the first invasion in 2014. This early wave of children never turned up in the Russian federal database; as part of a much smaller-scale operation, they were immediately matched with adoptive families and foster parents upon arrival. As one staffer at the International Criminal Court told the banned Russian news outlet iStories, “They’ve abducted more children than their system of guardianship, created back in 2014, could take in. The couples who used to adopt new children without any problems already had their hands full, and newcomers have nowhere to go" ("An Arctic Welcome"). A number of Ukrainian mothers have traveled to Russia to reclaim their children, some of whom have special needs, but most of the kidnapped minors remain in the Russian Federation .

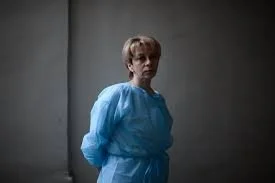

In contrast to the furor sparked by the underage population transfer that has been taking place since the 2022 invasion, the transportation of Ukrainian children between 2014 and 2022 drew little attention in the international media. One likely reason may have been geographical: all the children taken to Russia during this first wave were from Donbas, which was under separatist control. There were no pro-Kyiv local authorities to protest, and a larger portion of the civilization population with emotional and political ties to Russia. This, in turn, facilitated the Russian media's portrayal of the children's removal as part of a humanitarian mission. According to a study by the European Resilience Initiative Center, the process began in December 2014 under the aegis of a Russian humanitarian celebrity, Elizaveta Glinka, better known to the Russian-speaking population as "Doctor Liza."

Doctor Liza

At least officially, the children transported by Doctor Liza were part of a much narrower category than those in the post-2022 wave: the ones who were the object of extensive Russian media coverage were patients in Donbas hospitals evacuated to Russia for treatment, a move made possible by Putin's favorable response to her request to amend Russia's laws to allow medically-justified transfers of Ukrainian children. Doctor Liza's motivations may well have been humanitarian, but they both facilitated and were facilitated by a discourse that denied any serious distinction between Ukrainians and Russians (not to mention the border between their two countries). Publicly, Doctor Liza also denied that the Russian military was involved in a conflict she described as a "civil war." Doctor Liza's death in a 2016 plane clash effectively foreclosed any public debate about her actions, cementing the reputation she had already gained as a "Russian Mother Theresa."

The Russian authorities continue to frame their actions as a humanitarian relief effort, but the irony is difficult to ignore. The RF's previous children's rights' ombudman, Pavel Astakhov, was responsible for fomenting propaganda about the mistreatment of Russian children at the hands of liberal Europeans, and was a key figure in the implementation of the Dima Yakovlev law banning foreign adoption of Russian children. His replacement, Maria Lvova-Belova, is now internationally notorious for facilitating the illegal adoption of Ukrainian children by Russian nationals.

No one who had ever known Maria Lvova-Belova early in her career would have supposed her destined to be the target of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant. Like Doctor Liza, she exemplifies the curious slippage between Russian disability and child welfare activism on the one hand and aggressive Russian imperialism on the other. The biological mother to five children and adopted mother of eighteen more, in 2008 she co-founded Blagovest, an NGO dedicated to the social adaptation of orphans. Six years later, she started the Louis Quarter, for disabled orphans who had aged out of institutional care but needed assistance to learn how to live independently. Both organizations were meant to fill a desperate need in Russian society, and they also have the advantage of being part of some of the few non-governmental sectors that the Putinist state continues to support: those related to disability and adoption. Lvova-Belova was an adoption advocate in both her public and private life before the Dima Yakovlev law was passed, and the activities she and her allies engaged in would prove useful in its aftermath, when the government wanted to show that domestic efforts made foreign adoption unnecessary.

But the nationalist and conservative character of her charity work was clear enough: Lvova-Belova is also part of social activism rooted in Russian Orthodoxy. "Blagovest" takes its name from the Orthodox bell wringing peal called the Annunciation of the Good News. Her work with orphans and the disabled is accompanied by strong opposition to abortion (a practice that was not particularly controversial in the Soviet Union or Russia until Western right-wing groups began working with Russian counterparts to push for a ban). Adopting eighteen children is certainly unusual, but, perhaps ironically, it echoes the very phenomenon that was demonized during the Dima Yakovlev years: religious, altruistic parents "called" to expand their families through adoption. In the United States, the "Quiverfull" movement that encourages multiple adoptions helps promote a Christian Nationalist agenda: bringing more babies to Christ not only saves souls, it can eventually shift the balance at the polls as well. Activists like Belova may consider their choices apolitical, but any such pretense disappears in the context of Russia's invasions of Ukraine. Lvova-Belova herself has adopted a fifteen-year old from Mariupol, the eastern Ukrainian city that was all but razed to the ground during a Russian siege in 2022.

Whatever the ethnic and linguistic background of this particular teenager, Lvova-Belova is effectively russifying them by placing them in a domestic and educational context that denies Ukrainian sovereignty and casts doubt on the very existence of Ukraine as a people and culture. Reports from the "summer camps," schools, and institutions in which many of the displaced Ukrainian find themselves suggest that they are kinder, gentler reeducation camps. Like all children in the Russian Federation, they are obliged to attend the new classes called "Conversations about What's Important," which are canned lessons in Russian patriotism whose name resembles a popular 1990s series of nostalgic Soviet-style musical specials ("Songs about What's Important"). These classes peddle the Putinist narrative of Russian greatness, as well as the state's interpretation of Russia's war in Ukraine. Belova-Lvova herself attests to the efficacy of Russian patriotic education:

[Belova-Lvova] acknowledged that at first, a group of 30 children brought to Russia from the basements of Mariupol defiantly sang the Ukrainian national anthem and shouted, “Glory to Ukraine!” But now, she said, their criticism has been “transformed into a love for Russia,” and she herself has taken one in, a teenager.

“Today he received a passport of a citizen of the Russian Federation and does not let go of it!” she posted on Telegram on Sept. 21, along with a photo. “(He) was waiting for this day in our family more than anyone else.”

Thanks to Belova-Lvova's influence with Putin, all the children brought from Ukraine are immediately eligible for Russian citizenship, a fact that reinforces just how instrumental these forced adoptions are to the new Putinist conception of Russianness as something simultaneously primordial (associated with nature, with the soil), voluntary (as a matter of allegiance) and actuarial/biopolitical (a function of one's passport). As Russia expands beyond its post-Soviet borders, so too does its definition of the Russian stretch to accommodate the new reality that the leadership hopes to create on the ground.

Sting's hope was not in vain. The Russians do love their children, and their (expansionist, aggressive) love is a force that makes "their" children Russian.

Next: What Child Is This?