The Three Faces of Rogue

In Rogue, Claremont finds the perfect vehicle for so many of his preoccupations: trauma, certainly, but also duality: when Jean Grey says that part of her wants one thing, while another part wants something different, she may be speaking metaphorically (though she may also be speaking about the Phoenix Force), but Rogue is actually trying to cope with having two different people inside her head. While at times this can look like Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), there is a crucial difference. A person with DID develops alters in response to trauma, but these alters stem from the core self. Rogue's "alter" not only did not come from within herself; she is a completely different person with her own life experiences. Moreover, the Carol persona is the source of trauma rather than a mechanism for defense. Carol is the trauma, and, as a continued presence in Rogue's head, she is trauma as an ongoing process. She is also a constant reminder of Rogue's own guilty: Carol's presence as a source of emotional pain is simultaneous the absence that torments the original Carol Danvers. The former Ms. Marvel's terrible loss is Rogue's unbearable excess.

Throughout the first few years of Rogue's presence on the team, Claremont uses Carol's spectral presence sparingly. When she first explains her problem in Uncanny X-Men 171, we only have her description of her personality problem, rather than a direct representation of her experience. Most of the time, Rogue's psychological troubles manifest through her fear of physical contact and concomitant sense of isolation. But on three significant occasions, Carol's persona takes center stage.

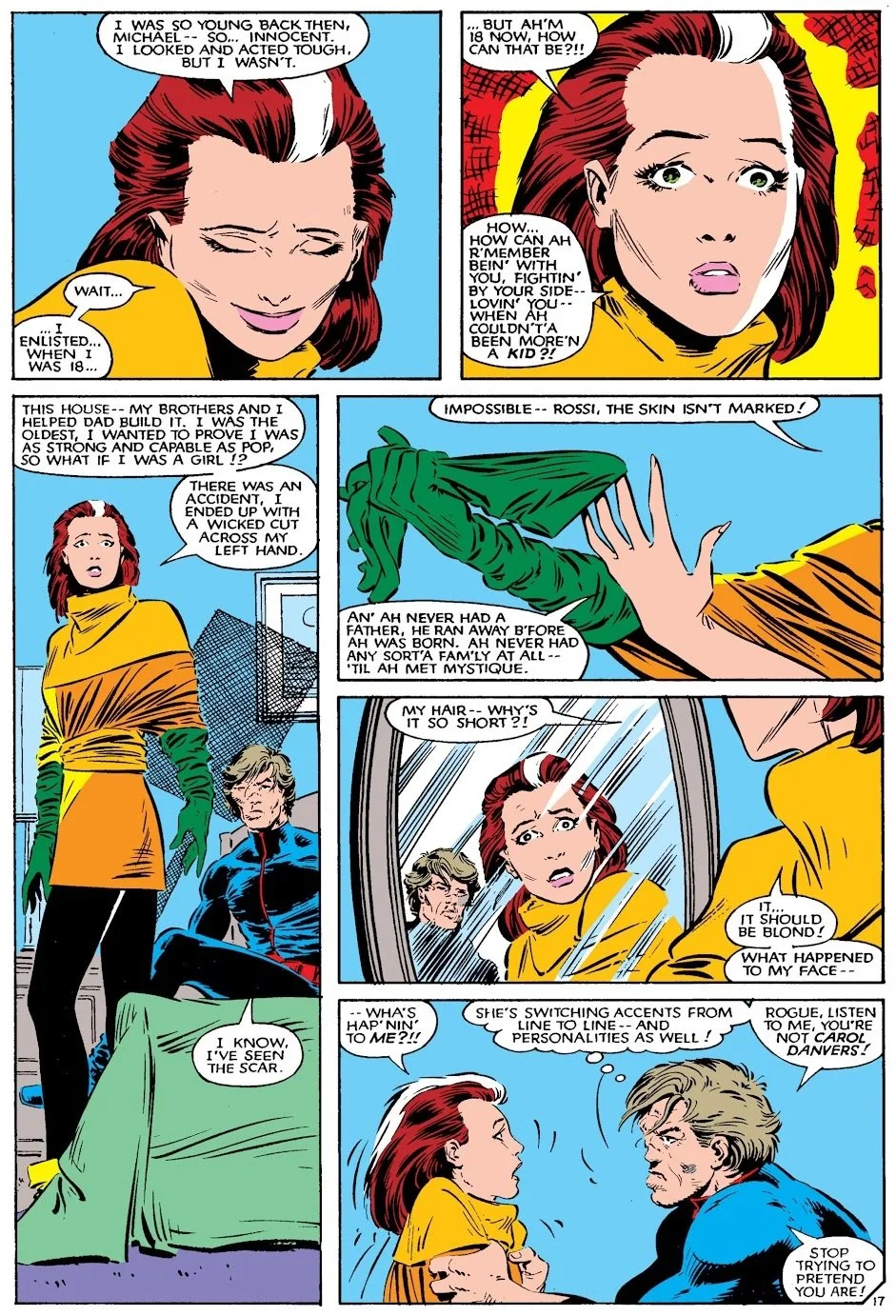

Nearly a year after she joins the X-Men, "Madness" (Uncanny X-Men 182, with art by John Romita Jr and Dan Green) starts out as a solo Rogue story before demonstrating the impossibility of the idea: Rogue is never really solo. The issue begins on an unusually carefree note for Rogue, as she flies back to Westchester from Japan (where the X-Men were teleported at the end of the first Secret Wars event). But she is also exhausted, and her guard is down. When she hears a voicemail from Michael Rossi, Carol's former espionage partner and lover, she flies off to rescue a man whom she has never actually met. As she breaks her way into the helicarrier where he is held captive, she still thinks and acts like Rogue, until she catches sight of the injured Rossi. Without realizing it, she immediately takes on Carol's voice and Boston accent, not to mention her life experience, telling him: "Me and the bad penny, lover, forever popping up where and when least expected."

The rest of the issue is a two-person psychodrama--three, if we count not just Rogue and Rossi, but Carol. What makes it all so compelling is the lack of clear boundaries between Rogue and Carol. Rogue is dissociating, and there are moments when she seems to be speaking entirely in one voice or the other, but they appear to be experiencing "co-consciousness;" rather than blacking out and being unaware of what happens, "Rogue" and "Carol" are this point different modes adopted by the body's core self. She reacts to Rossi with Carol's love, memories, and attitudes, but her own body reminds her that she is Rogue (she lacks Carol's scars and is much younger). Fleeing the house where she has brought Rossi to recover, Rogue briefly experiences Carol's childhood, which brings her fleeting moments of happiness, but soon her tour of Carol's life forces her to re-experience the core trauma of her assault on Ms. Marvel, this time from both sides. This is the essence of her torture: she is always Rogue, guilty for her actions and suffering the consequences, and she is also always Carol, an entirely different woman whose emotional life is available only to Rogue. She tells Rossi, "Ah'm Carol--in all the ways that counts!" but Rossi rejects her: "I wish there was some way to make you pay for what you've done. / I wish I had the power to kill you." Rogue's response is perfect: "So do I, my love. / So do I." Her Southern accent is missing; she is speaking in Carol's voice, for both of them.

It makes sense that the contrast between the eighteen-year-old Rogue and the thirtysomething Carol comes to a head during an encounter with a man Carol loved. Though Rogue is repeatedly depicted as sensual and playful (basking in male attention while wearing a bikini in Uncanny X-Men 185 ("Public Enemy!", with art by John Romita, Jr and Dan Green)), her powers render impossible the kind of intimacy that is so central to the memories and emotions of the more mature Carol. Any skin-to-skin contact initiates the transfer of abilities, thoughts, and feelings, but again and again, Rogue activates her powers by kissing. A twenty-first century reader might find this disturbingly non-consensual, but that is in keeping with the nature of Rogue's mutation: consent is rarely involved.

Her first playful, romantic encounter with a boy was also the first time her powers activated, leaving him comatose; kissing as a weapon is a reenactment of the adolescent trauma her mutation caused her. It is also one of the few moments that she can experience the physical contact she has been denied since puberty. Her bungled attack on Ms. Marvel, then, could easily be understood as a metaphor for sexual assault, were it not for the fact that the entire episode was part of Claremont's attempt to recover the character after the assault on her in Avengers 200. When Carol regains consciousness and selfhood with the aid of Professor Xavier, it is the Avengers she needs to confront, not Rogue. Their actions were a betrayal of trust and friendship; Rogue was an opponent she barely knew.

During a heartfelt conversation between Rogue and Storm in "Public Enemy!" (showing just how much progress the two have made with each other since Storm's initial declaration that she would leave the X-Men if Rogue were inducted), Storm realizes for the first time exactly how closed off Rogue has been: "Rogue--has every exercise of your power been an act of violence? Has no one ever given himself of his own free will?" Ororo lets Rogue take her hand and experience her world without resisting, and it is a revelation. Though the contact is not explicitly sexual, it is certainly consistent with Claremont's long-running lesbian subtexts (Storm and Yukio, for instance), and it offers a small bit of hope that Rogue can find a way to make real human contact.

Next: Casting out the Ghost